|

|

|

|

|

For example is not proof but it does show that something is possible.

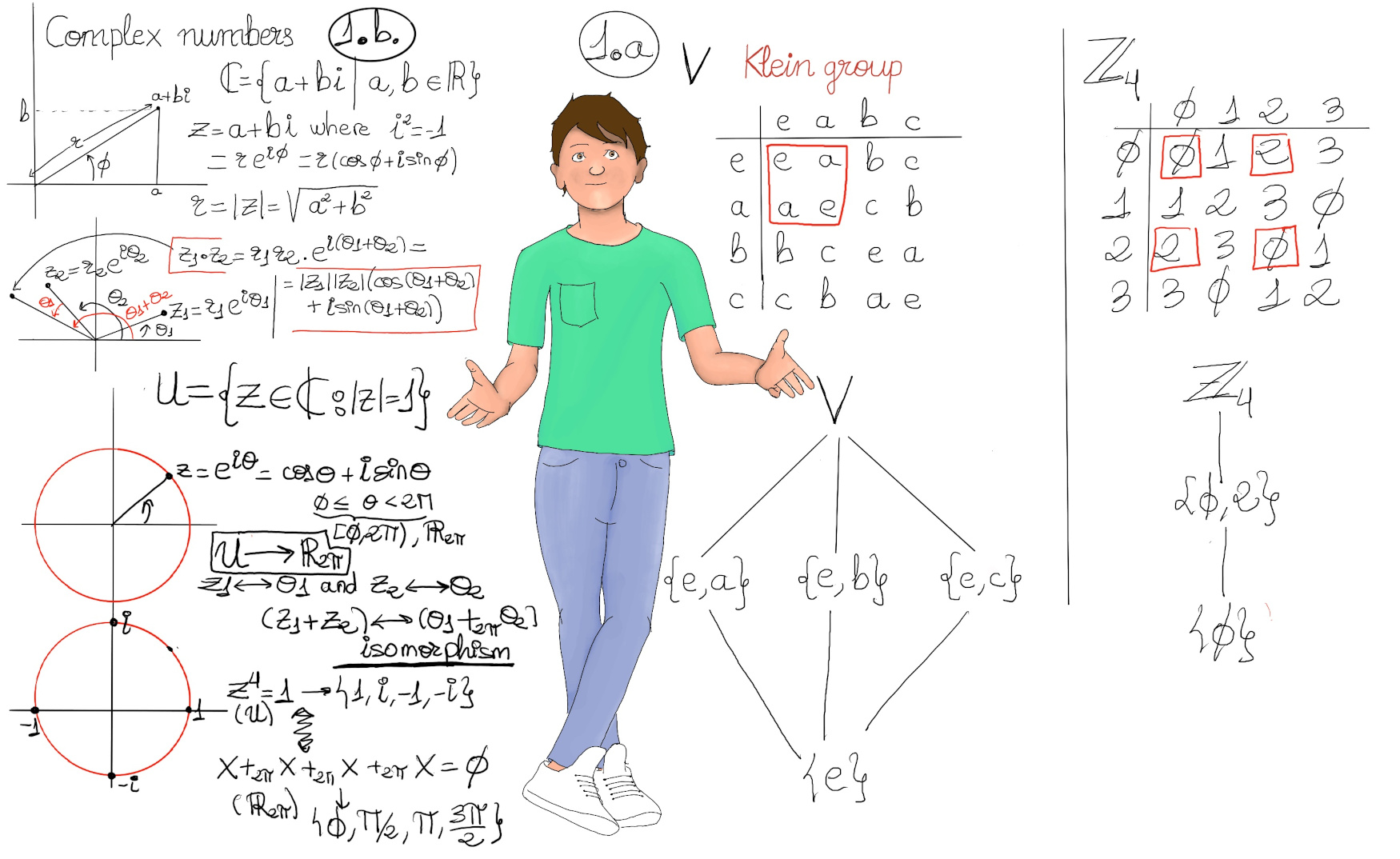

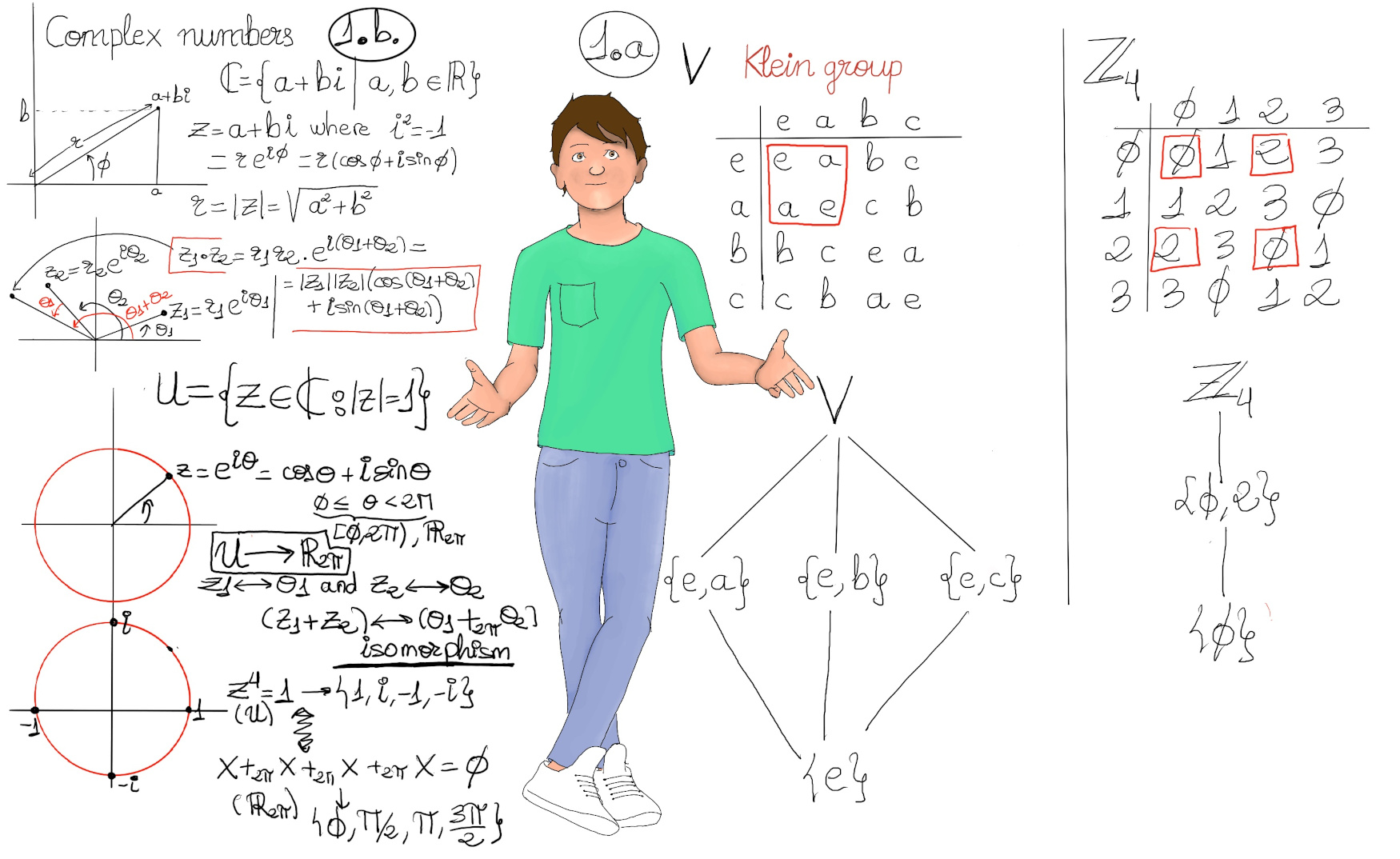

Definition. Let G be a group. A subgroup is a subset of a group which is also a group of its own, that is, that follows all axioms that are required to form a group. Formally, H ⊂ G (H is a subset of G), ∀a, b ∈ H, a·b ∈ H, and (H, ·) is a group (closure, identity, and inverses).

We use the notation H ≤ G to mean that H is a subgroup of G. Every group G has at least two trivial subgroups: the group G itself and the subgroup {e} containing only the identity element. Notice that {e}, a set, is different than e, the identity element.

All other subgroups are said to be nontrivial or proper subgroups, and we express it as H < G.

Let r be the counterclockwise rotation by θ = $\frac{2π}{n}$, then the n rotations in Dn are e, r, r2, ···, rn-1, namely e2π/n, e2(2π/n), ···, e(n-1)2π/n. If {a1, a2, ···, an} denotes the vertices of a n-gon, the cyclic permutation α = (a1, a2, ···, an) ∈ Sn is the rotation r. Chose any vertex, e.g. a1, and consider it the fixed point of a reflection of the plane, i.e., the permutation β = (a2, an)(a3, an-1)··· ∈ Sn. Since Dn is generated by α and β ∈ Sn ⇒ Dn ≤ Sn

Using matrix multiplication, we have Q8 = {±1, ±i, ±j, ±k} and i2 = j2 = k2 =−1, ij = −ji = k, jk = −kj = i, ki = −ik = j. Moreover, 1 is the identity of Q8, it is closed under matrix multiplication, and contains the inverse of every element, so it is a subgroup of GL(2, ℂ).

Two-Step Subgroup Test. Let G be a group, a non empty subset H ⊂ G is a subgroup (H ≤ G) iff (it is short for if and only if)

Proof:

If H is a subgroup, then (i) and (ii) obviously hold.

Conversely, suppose (i) and (ii). The associative o grouping property is inherited from the group product of G.

∀a ∈ H, a-1 ∈ H (ii) ⇒ a(a-1) = (a-1a) = e ∈ H (i) ⇒ e is a neutral element of G, so it is a neutral element of H ⇒ H has a neutral element and every element in H (∀a ∈ H) has an inverse element.

Examples.

Proof. If z, w ∈ $\Tau$, z = cosθ + i sinθ = eiθ, w = cosΦ + isinΦ = eiΦ. zw = eiθeiΦ = ei(θ + Φ) = cos(θ + Φ) + i sin(θ + Φ), zw ∈ $\Tau$ so it is closed.

This is basic stuff, z, w ∈ ℂ, z = r(cosθ + i sinθ), w = s(cosΦ + isinΦ), then zw = rs(cos(θ + Φ) + i sin(θ + Φ)).

If z ∈ $\Tau$, z = a + ib, r = |z| = $\sqrt{a^{2}+b^{2}} = 1$, z-1 = $\frac{a-bi}{a^{2}+b^{2}} = a - bi,$ and r’ = |z-1| = $\sqrt{a^{2}+(-b)^{2}} = 1$ ⇒ z-1 ∈ $\Tau$.

Theorem. One-Step Subgroup Test. Let G be a group, a non empty arbitrary subset of G, H ⊆ G, is a subgroup of G (H ≤ G) iff ∀a, b ∈ H, a·b-1 ∈ H.

Proof. If H ≤ G, ∀a, b ∈ H ⇒ [H subgroup ⇒ inverses] b-1∈ H ⇒[Closed operation] a·b-1 ∈ H.

Conversely, suppose a non empty arbitrary subset of G, say H ⊆ G, and ∀a, b ∈ H, a·b-1 ∈ H. In particular, take a = b ⇒ b·b-1 = b-1·b = e ∈ H ⇒ e is a neutral element of G, so it is a neutral element of H ⇒ H has G’neutral element e and any arbitrary element in H, say b ∈ H, has an inverse element, b-1∈ G ⇒ [e, b ∈ H] e·b-1 = b-1 ∈ H.

Closed operation. ∀a, b ∈ H, let’s show that their product is also in H. We know that b-1 ∈ H ⇒ (b-1)-1 ∈ H ⇒ a·(b-1)-1 = ab ∈ H ∎

Theorem. Finite Subgroup Test. Let G be a group,a non empty finite subset of G is a subgroup if and only if it is closed under the operation of G,i.e., H ⊆ G, |H| = n, such that ∀a, b ∈ H, a·b ∈ H ⇒ H ≤ G.

Proof. Using the Two-Set Subgroup Test, we only need to prove that a-1 ∈ H, ∀a ∈ H.

If a = e ⇒ [By assumption, H is closed under the operation of G] ee = e ∈ H and a-1 = e ∈ H.

If a ≠ e ⇒ a, a2, a3,… belong to H because H is closed under the operation of G (∀a, b ∈ H, a·b ∈ H, so a·a = a2 ∈ H and so on). However, since H is finite, this process will necessary produce repetitions ⇒∃i, j: ai = aj and i > j ⇒ ai-j = e ∈ H ⇒ [∃i, j such that i-j > 0, ai-j∈ H] Therefore, a-1 = ai-j-1 ∈ H because 0 ≤ i-j-1 < i-j and a · ai-j-1 = ai-j-1 · a = ai-j = e∎

Proposition. Subgroup relation is transitive. If K is a subgroup of G, and H is a subgroup of K, then H is a subgroup of G, H ≤ K ≤ G ⇒ H ≤ G.

Proof.

H ≤ K ≤ G ⇒ H ⊆ K ⊆ G ⇒ H is a subset of G, H ⊆ G. The closure of H under G’s operation is not changed, whether you are looking at H as a subset of K or G under the same group operation.

Futhermore, since the identity element in G, say eG, is unique ⇒ eG = eK = eH. Similarity, ∀a ∈ H, a-1 ∈ H (H ≤ K), and this inverse is also unique (Uniqueness of identity and inverses.) ∎

Proposition. Intersection of two subgroups of a group is again a subgroup. If H ≤ G, L ≤ G, then H∩L ≤ G.

Proof: ∀a, b ∈ H∩L, a, b ∈ H and a, b ∈ L ⇒ [H ≤ G, L ≤ G, and One-Step Test] a·b-1 ∈ H and a·b-1 ∈ L ⇒ a·b-1 ∈ H∩L∎

Examples. Let G be a group and a be any element in G (a ∈ G). Then, a generating set of a group is a subset of the group such that every element of the group can be expressed as a combination (under the group operation) of finitely many elements of the subset and their inverses. In particular, the set ⟨a⟩={an | n ∈ Z} is the cyclic subgroup generated by a.

Proof: a0 = e ∈ ⟨a⟩. g, h ∈ ⟨a⟩, g = am, h = an for some m, n ∈ ℤ, gh = am+n ∈ ⟨a⟩, m+n ∈ ℤ; g-1 = a-m ∈ ⟨a⟩ (ama-m = a0 = e, -m ∈ ℤ)∎

Examples: