“You are not even an insignificant and useless human being, but just a low-level, primitive, bug-like, and oxygen-thief life-form. You really are an impossible to underestimate loose collection of personal flaws, unresolved personal traumas, a fully-fledged package of dark areas and unconscious biases, combined into an unholy, grotesque, and humiliating succession of frightening mistakes and unfortunate circumstances,” the healthcare worker took a few seconds to breath, Apocalypse, Anawim, #justtothepoint.

Definition

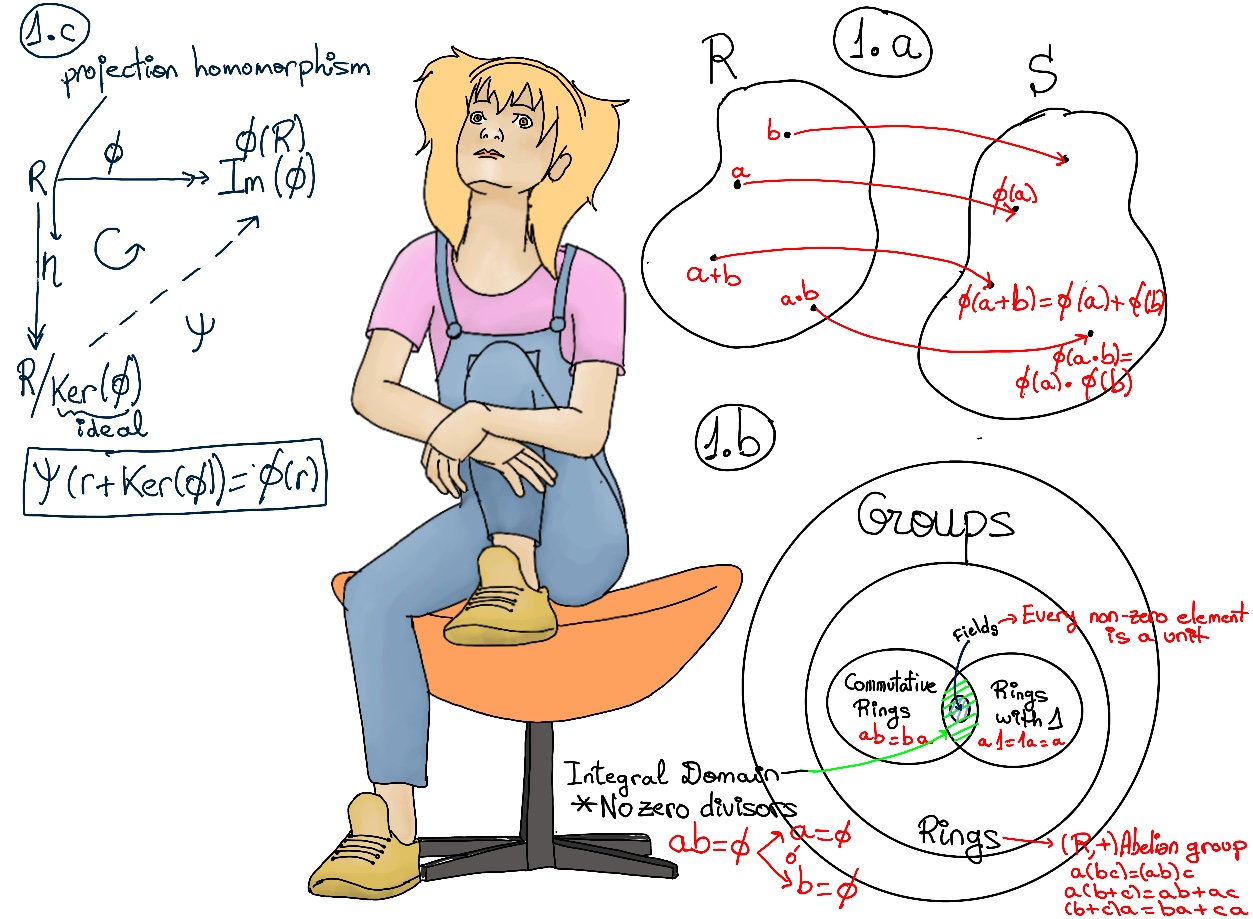

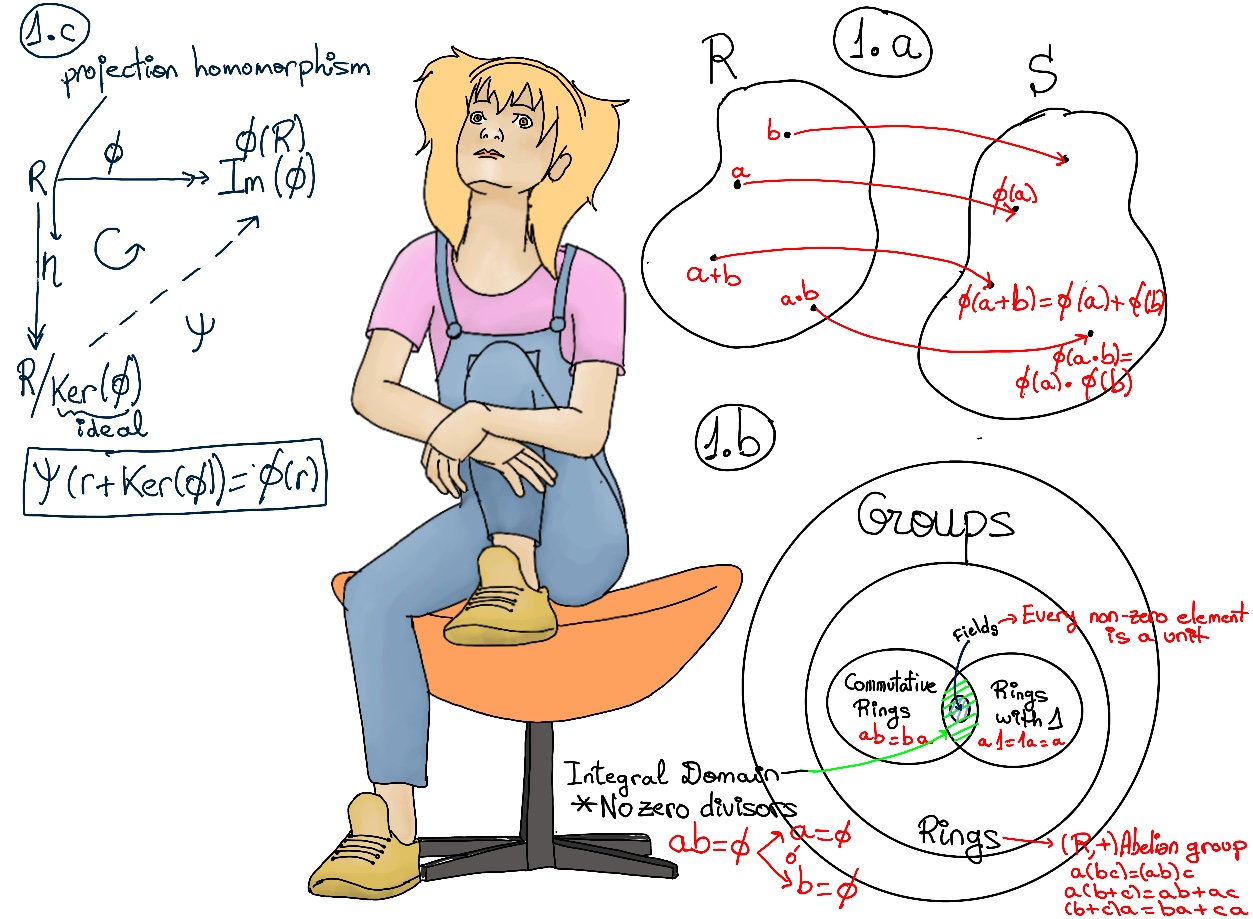

A ring homomorphism Φ from a ring R to a ring S is a structure-preserving function or mapping between two rings. More explicitly, it is a function Φ: R → S such that Φ is addition, multiplication, and unit (multiplicative identity) preserving, Φ(a + b) = Φ(a) + Φ(b), Φ(ab) = Φ(a)Φ(b), Φ(1R) = 1S, ∀a, b ∈ R. Figure 1.a.

💣In our original definition, a ring does no need to have a multiplicative identity, other authors define a ring to have a multiplicative identity and, without the requirement for a multiplicative identity, such a construct is instead called a rng, a non-unital ring or pseudoring. Φ(1R) = 1S only obviously applies when a ring do have a multiplicative identity.

- A ring isomorphism is a ring homomorphism that is both one-to-one and onto. It is used to show that two rings are algebraically identical.

- The kernel of a ring homomorphism is the set of elements of R which are mapped to zero, Ker(Φ) = {r ∈ R| Φ(r) = 0}, where 0 is the additive identity.

- The image of a ring homomorphism is the set of elements in the codomain S that are imaged of some elements in the domain R, im(Φ) = Φ(R) = {s ∈ S | s = Φ(r) for some r ∈ R}.

Examples

- ∀n ∈ ℤ, n > 0, the function Φ: ℤ → ℤn defined by Φ(m) = [m] = m mod n is a surjective (it is very obvious that we can hit every element on ℤn) ring homomorphism.

- Addition. This has already being taken care of because we have checked it previously regarding group homomorphisms.

- ∀m1, m2 ∈ ℤ, Φ(m1 · m2) = [m1m2] = [m1][m2] = Φ(m1)Φ(m2).

- Ker(Φ) = nℤ.

-

Φ: ℝ[x]→ ℂ, Φ(f(x)) = f(i) is a ring homomorphism. If f(x) ∈ Ker(Φ) ⇒ Φ(f(x)) = f(i) = 0 ⇒ f(x) = (x-i)g(x) where g(x) ∈ ℂ[x] ⇒[By assumption, f(x) need to “live” in ℝ[x], Φ domain] f(x) = (x-i)(x+i)f’(x) where f’(x) ∈ ℝ[x] and we are not talking about derivate ⇒ f(x) = (x2+1)f’(x) where f’(x) ∈ ℝ[x]. Therefore, Ker(Φ) = (x2+1)ℝ[x].

-

The complex conjugation Φ: ℂ → ℂ, Φ(a + bi) = a - bi is a ring homomorphism.

-

Let ℚ[x] be the ring of all polynomials with rational coefficients, the function ℚ[x] → ℝ, Φ(f(x)) = f($\sqrt{2}$) is a ring homomorphism. Im(Φ) = ℚ[$\sqrt{2}$] = {a + b$\sqrt{2}$ | a, b ∈ ℚ}

Proof:

-

∀ p(x), q(x) ∈ ℚ[x], Φ(p(x) + q(x)) = $p(\sqrt{2}) + q(\sqrt{2})$ = Φ(p(x)) + Φ(q(x)).

-

Φ(p(x)·q(x)) = $p(\sqrt{2})q(\sqrt{2})$ = Φ(p(x))Φ(q(x)).

-

Ker(Φ) = {p(x) ∈ ℚ[x] | $p(\sqrt{2})=0$)}. Notice that p(x) ∈ Ker(Φ) ⇒ $p(\sqrt{2})=0 ⇒ [\sqrt{2}~ is~ a~ root~ of~ this~ polynomial] p(x)=(x-\sqrt{2})q(x)$ this is going on over ℝ[x] ⇒ $p(x)= (x-\sqrt{2})(x+\sqrt{2})q’(x)$, q’(x) ∈ ℚ[x] ⇒ p(x) = (x2 -2)q’(x). Therefore, Ker(Φ) = {(x2 -2)p(x) | p(x) ∈ ℚ[x]} = (x2 -2)ℚ[x].

- Let ℝ[x] be the ring of all polynomials with real coefficients, the function Φ: ℝ[x] → ℝ, Φ(f(x)) = f(1) is a ring homomorphism, too.

- Φ: ℤ2 → ℤ2, Φ(x) = x2.

- Φ(x + y) = (x + y)2 = x2 + 2xy + y2 = [2xy=0 because 2 times anything is 0 in ℤ2] x2 + y2 = Φ(x) + Φ(y).

- Φ(xy) = (xy)2 = x2y2 = Φ(x)Φ(y)

- Φ(x + y) = [x + y = 4q1 + r1, 0 ≤ r1 < 4] 5·4·q1 + 5·r1 = 5·r1. Φ(x) + Φ(y) = 5x + 5y = 5(x + y) = 5·r1.

- Φ(xy) = [xy = 4q2 + r2, 0 ≤ r2 < 4] 5·4·q2 + 5·r2 = 5·r2. Φ(x)Φ(y) = 5x · 5y = 5·5(xy) = 5·(5·r2) = (5·5)·r2 [5·5 = 5 in ℤ10] 5·r2.

- For a ring R of prime characteristic p, Φ: R → R defined by Φ(r) = rp is a ring endomorphism called the Frobenius endomorphism.

Φ(a + b) = (a + b)p =[(a + b)p can be expanded using the binomial theorem] $\sum_{i=0}^{i=p} {{p}\choose{i}} a^ib^{p-i}$ where ${{p}\choose{i}}=\frac{p!}{i!(n-i)!}$ 0 ≤ i ≤ p. If 1 ≤ i ≤ p-1, p divides ${{p}\choose{i}}=\frac{p!}{i!(n-i)!}$ so the coefficients of all the terms except ap and bb vanish ⇒ Φ(a + b) = (a + b)p = ap + bp = Φ(a) + Φ(b). Φ(a·b) = (a·b)p = ap·bp = Φ(a)·Φ(b).

- Non-examples: There is no non-trivial ring homomorphism ℤ → ℤ/nℤ for any n ≥ 1. If m ≠ n, then mℤ is not isomorphic to nℤ.

Consider a ring homomorphism Φ: ℤ → ℤ/nℤ, 12 = 1 ⇒ Φ(12)= Φ(1) ⇒ Φ(12) = Φ(1·1) = Φ(1)·Φ(1) = Φ(1)2 = Φ(1). The only element in ℤ/nℤ that is identical to its square is zero, so Φ(1) = 0. However, Φ(k) = Φ(1+ ··· (k times) ··· + 1) = kΦ(1) = k·0 = 0, Φ = 0. The only ring homomorphism is the trivial one.

Consider a ring isomorphism Φ: nℤ → mℤ, a ring isomorphism must take generators to generators, n would have to be mapped to ±m. Consider the case of Φ(n) = m (without losing generality). Φ(n·n)= Φ(n + n + ··n times ·· + n) = Φ(n) + Φ(n) + ··n times ·· + Φ(n) = m + m + ··n times ·· + m = nm. However, Φ(n·n) = Φ(n)Φ(n) = mm. Therefore nm = mm, but n ≠ m ⊥

A similar reasoning shows that ℤ and 2ℤ are not isomorphic, since 1 is a generator of ℤ, Φ(1) is a generator of 2ℤ, Φ(1) = ±2. Then Φ(1) = Φ(1·1)= Φ(1)Φ(1) = 4 in both cases, but the same element in order to be one-to-one cannot be mapped to two different elements, namely ±2 and 4⊥.

- There is no ring isomorphism between 2ℤ and 3ℤ. Suppose Φ: 2ℤ → 3ℤ, Φ(2) ∈ 3ℤ, Φ(2) = 3n, n ∈ ℤ. Φ(4)= Φ(2+2) = Φ(2) + Φ(2) = 3n + 3n = 6n. Besides, Φ(4)= Φ(2·2) = Φ(2) · Φ(2) = 3n · 3n = 9n2 ⇒ 6n = 9n2 ⇒ [Φ(2) = 3n, n ≠ 0. If n = 0, Φ(2) = Φ(0) = 0 which contradicts Φ is one-to-one] 2 = 3n ⇒ n = 2/3 ∉ ℤ ⊥

- There is no ring isomorphism between ℚ[$\sqrt{2}$] and ℚ[$\sqrt{3}$].

Suppose Φ: ℚ[$\sqrt{2}$] → ℚ[$\sqrt{3}$] is a ring isomorphism, Φ($\sqrt{2}$) = a + b$\sqrt{3}$ for some a, b ∈ ℚ, not both zero.

Φ(2) = $Φ(\sqrt{2})Φ(\sqrt{2})= (a + b\sqrt{3})^{2}=a^{2}+3b^{2}+2ab\sqrt{3}$

Φ(2) = Φ(1+1) = Φ(1) + Φ(1) = [By assumption, then the identity is carried] 1 + 1 = 2 ⇒[2 = $a^{2}+3b^{2}+2ab\sqrt{3}$] 2$ +0\sqrt{3} =a^{2}+3b^{2}+2ab\sqrt{3}$ ⇒ $2=a^{2}+3b^{2}, 2ab = 0$ that is a = 0 or b = 0. If a = 0 ⇒ 3b2= 2 ⇒ b = $\sqrt{\frac{2}{3}}$ ∈ ℚ ⊥. If b = 0 ⇒ a2 = 2 ⇒ a = $\sqrt{2}$ ∈ ℚ ⊥

- Test for Divisibility by 9. Let n ∈ ℤ with decimal representation akak-1···a0, n = ak10k + ak-110k-1 + ··· + a0. Let Φ be the natural homomorphism from ℤ to ℤ9, Φ(n) = n mod 9.

n is divisible by 9 ↭ 0 = Φ(n) ↭ 0 = Φ(ak10k + ak-110k-1 + ··· + a0) = Φ(ak)(Φ(10))k + Φ(ak-1)(Φ(10))k-1 + ··· + Φ(a0) = [Φ(n) = n mod 9, in particular Φ(10) = 1] Φ(ak) + Φ(ak-1) + ··· + Φ(a0) = Φ(ak + ak-1 + ··· + a0) ↭ ak + ak-1 + ··· + a0 is divisible by 9

- Φ:ℂ → M2x2(ℝ) is a homomorphism defined by Φ(a + bi) = $(\begin{smallmatrix}a & -b\\ b & a\end{smallmatrix})$

- Φ((a + bi) + (c + di)) = Φ((a+c) + (b+d)i) = $(\begin{smallmatrix}a + c & -(b + d)\\ (b + d) & a + c\end{smallmatrix}) = (\begin{smallmatrix}a & -b\\ b & a\end{smallmatrix}) + (\begin{smallmatrix}c & -d\\ d & c\end{smallmatrix}) $ = Φ(a + bi) + Φ(c + di).

- Φ((a + bi)(c + di)) = Φ((ac-bd) + (ad+bc)i) = $(\begin{smallmatrix}ac-bd & -(ad+bc)\\ ad+bc & ac-bd\end{smallmatrix}) = (\begin{smallmatrix}a & -b\\ b & a\end{smallmatrix}) (\begin{smallmatrix}c & -d\\ d & c\end{smallmatrix}) $ = Φ(a + bi)Φ(c + di).

- a + bi ∈ Ker(Φ) ⇒ Φ(a + bi) = $(\begin{smallmatrix}a & -b\\ b & a\end{smallmatrix}) = (\begin{smallmatrix}0 & 0\\ 0 & 0\end{smallmatrix})$ then a = b = 0 ⇒ Ker(Φ) = {0} ⇒ Φ is injective.

Im(Φ) = {$(\begin{smallmatrix}a & -b\\ b & a\end{smallmatrix})$ | a, b ∈ ℝ} ⊆ M2x2(ℝ) ⇒ ℂ ≋ Im(Φ).

-

Φ, Φ’, Φ’’:M2x2(ℝ) → ℝ defined by Φ$(\begin{smallmatrix}a & b\\ c & d\end{smallmatrix})$ = a, Φ’$(\begin{smallmatrix}a & b\\ c & d\end{smallmatrix}) = det(\begin{smallmatrix}a & b\\ c & d\end{smallmatrix})$, and Φ’’$(\begin{smallmatrix}a & b\\ c & d\end{smallmatrix}) = trace(\begin{smallmatrix}a & b\\ c & d\end{smallmatrix}) = a + d$ are not homomorphisms, because Φ(ab)≠Φ(a)Φ(b).

-

Exercise. Find all ring homomorphisms, Φ: ℤxℤ → ℤ, Φ(1, 0) = m, Φ(0, 1) = n ⇒ Φ(0, 0) = Φ((0, 1)·(1, 0)) = m·n. Φ(0, 0) = [Φ ring homomorphism, Φ transports the addition identity] 0 ⇒ mn = 0 ⇒ m = 0 or n = 0. Without any loss of generality, let’s assume m = 0.

Φ(a, b) = Φ((1, 0) + ··· (a times) ··· (1, 0) + (0, 1) + ··· (b times) ··· + (0, 1)) = Φ(1, 0) + ··· (a times) ··· Φ(1, 0) + Φ(0, 1) + ··· (b times) ··· + Φ(0, 1) = am + bn = [By assumption, m = 0] bn

- Case 1. m = 0. Φ(a, b) = bn. Ker(Φ) = ℤ x {0}. Im(Φ) = nℤ.

- Case 2. n = 0. Φ(a, b) = am. Ker(Φ) = {0} x ℤ. Im(Φ) = mℤ.

Properties

Let Φ be a ring homomorphism from a ring R to another S, Φ: R → S. Let A be a subring of R and let B be an ideal of S.

0R = 0R + 0R ⇒ Φ(0R) = Φ(0R + 0R) =[Φ is addition preserving, Φ(a+b) = Φ(a) + Φ(b)] Φ(0R) + Φ(0R) ⇒ Φ(0R) = Φ(0R) + Φ(0R) ⇒[S is a ring, Φ(0R) has an additive inverse] 0S = Φ(0R) -Φ(0R) = (Φ(0R) + Φ(0R)) -Φ(0R) =[Associative] Φ(0R) + (Φ(0R) -Φ(0R)) ⇒ 0S = Φ(0R)∎

- Let R and S have multiplicative identities 1R and 1S respectively, then Φ(-1R) = -1S.

0S =[Previous property] Φ(0R) = Φ(1R -1R) =[Φ is addition preserving, Φ(a+b) = Φ(a) + Φ(b)] Φ(1R) + Φ(-1R)⇒ 0S = Φ(1R) + Φ(-1R) =[Φ is unit or multiplicative identity preserving] 1S + Φ(-1R) ⇒[0S = 1S + Φ(-1R)] Φ(-1R) = -1S.

- ∀r∈R, n∈ℤ+, Φ(nr) = nΦ(r) and Φ(rn) = (Φ(r))n.

∀r∈R, n∈ℤ+, Φ(nr) = Φ(r + r + ··n times·· + r) = Φ(r) + Φ(r) + ··n times·· + Φ(r) = nΦ(r).

∀r∈R, n∈ℤ+, Φ(rn) = Φ(r · r · ··n times·· · r) = Φ(r) · Φ(r) · ··n times·· · Φ(r) = Φ(r)n.

∀r ∈ R, 0S = Φ(0R) = Φ(r + (-r)) = Φ(r) + Φ(-r) ⇒ Φ(r) + Φ(-r) = 0S ⇒ Φ(-r) = -Φ(r).

- If r ∈ Rx then Φ(r) ∈ Sx and Φ(r-1) = Φ(r)-1.

∀ r ∈ Rx, ∃r-1 ∈ R: r·r-1 = r-1·r = 1R ⇒ Φ(r)·Φ(r-1) = Φ(r-1)·Φ(r) = Φ(1R) =[Φ is unit (multiplicative identity) preserving] 1S ⇒ Φ(r) has a multiplicative inverse and it is Φ(r-1).

- The homomorphic image of a subring is also a subring, that is, ∀A subring of R, Φ(A) = {Φ(a)| a ∈ A} is a subring of S.

- ∀a’1, a’2 ∈ Φ(A), ∃a1, a2 ∈ A: Φ(a1) = a’1, Φ(a2) = a’2. a’1 - a’2 = Φ(a1) - Φ(a2) =[∀r ∈ R, Φ(-r) = -Φ(r).] Φ(a1) + Φ(-a2) = Φ(a1 - a2) ∈ Φ(A) because a1 -a2 ∈ A subring of R.

- ∀a’1, a’2 ∈ Φ(A), ∃a1, a2 ∈ A: Φ(a1) = a’1, Φ(a2) = a’2. a’1 · a’2 = Φ(a1) · Φ(a2) = Φ(a1 · a2) ∈ Φ(A) because a1·a2 ∈ A subring of R.

- 1R ∈ A ⇒ Φ(1R) = 1S ∈ Φ(A).

- An onto ring homomorphism maps ideals on ideals, i.e., if A is an ideal of R and Φ is onto, then Φ(A) is an ideal of S.

Generally speaking, the homomorphism image of an ideal is not an ideal, e.g., let i: ℤ → ℚ, be the natural injection given by i(n) = n. ℚ is a field ⇒ [The only ideals of a field are {0} and the field itself] its only ideals are {0} and ℚ. Take any ideal ⟨n⟩ = nℤ ⊆ ℤ with n ≠ 0, i(⟨n⟩) = ⟨n⟩ = nℤ is not an ideal of ℚ.

- ∀a’1, a’2 ∈ Φ(A), ∃a1, a2 ∈ A: Φ(a1) = a’1, Φ(a2) = a’2. a’1 - a’2 = Φ(a1) - Φ(a2) =[∀r ∈ R, Φ(-r) = -Φ(r).] Φ(a1) + Φ(-a2) = Φ(a1 - a2) ∈ Φ(A) because a1 -a2 ∈ A ideal of R.

- ∀a’ ∈ Φ(A), ∃a ∈ A: Φ(a) = a’, ∀s ∈ S ⇒[Φ is onto] ∃r ∈ R: Φ(r) = s. Therefore, sa’ = Φ(r)Φ(a) = Φ(ra) ∈ Φ(A) because ra ∈ A (A is an ideal), hence sa’∈ Φ(A)∎

- The preimage of an ideal by a ring homomorphism is an ideal, i.e., Φ-1(B) = {r ∈ R | Φ(r) ∈ B} is an ideal of R.

I = Φ-1(B) = {r ∈ R | Φ(r) ∈ B}

- ∀a, b ∈ Φ-1(B), a - b ∈ Φ-1(B)? Φ(a), Φ(b) ∈ B, B is an ideal ⇒ Φ(a) - Φ(b) ∈ B ⇒ [Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(a) - Φ(b) = Φ(a) + Φ(-b) = Φ(a - b) Λ Φ(a) - Φ(b) ∈ B ⇒ a - b ∈ Φ-1(B).

- ∀r ∈ R, a ∈ Φ-1(B), then Φ(a) ∈ B, Φ(r) ∈ S, B is an ideal of S ⇒ Φ(r)Φ(a) ∈ B ⇒ [Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(r)Φ(a) = Φ(ra) ∈ B ⇒ ra ∈ Φ-1(B). Therefore, Φ-1(B) is an ideal of R.

- The homomorphic image of a commutative ring is commutative. In other words, if R is commutative, then Φ(R) is commutative.

Φ(R) = {Φ(r): r ∈ R}. ∀s1, s2 ∈ Φ(R), ∃r1, r2 ∈ R: Φ(r1) = s1, Φ(r2) = s2. s1·s2 =[By definition of Φ(R)] Φ(r1)Φ(r2) =[Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(r1r2) =[By assumption, R is commutative] Φ(r2r1) = [Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(r2)Φ(r1) = s2s1 ∎

- Let Φ: R → S be an onto homomorphism from a ring R with unit element. Then, Φ(1) is the unit element of S.

By assumption, Φ is onto, ∀s ∈ S, ∃r: Φ(r) = s. Φ(r)Φ(1) =[Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(r·1) =[R is a ring with unit element 1] Φ(r). Analogously, Φ(1)Φ(r) =[Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(1·r) =[R is a ring with unit element 1] Φ(r). Therefore, Φ(r)Φ(1) = Φ(1)Φ(r) = Φ(r) or ∀s ∈ S, ∃Φ(1)∈ S such that s·Φ(1) = Φ(1)·s = s ∎

- A ring homomorphism is injective iff its kernel is trivial. In other words, Φ is injective ↭ Ker(Φ) = {r ∈ R | Φ(r) = 0} = {0}.

Corollary. Φ is a ring isomorphism ↭ Φ is onto and its kernel is trivial.

⇒) Suppose Φ is injective. ∀r ∈ Ker(Φ), Φ(r) = 0S =[Φ is a ring homomorphism ⇒ Φ(0R) = 0S] Φ(0R) ⇒[Φ(r) = Φ(0S), Φ injective] r = 0R.

⇐) Suppose Ker(Φ) = {0R}. ∀r1, r2 ∈ R such that Φ(r1) = Φ(r2) ⇒ Φ(r1)-Φ(r2) = Φ(r1)+Φ(-r2) = Φ(r1-r2) = 0S ⇒ r1 - r2∈ Ker(Φ) = {0R} ⇒ r1 = r2 ⇒ Φ is injective ∎

- The inverse of a ring isomorphism is also an isomorphism or, in other words, Φ is a ring isomorphism ⇒ Φ-1 is isomorphism.

- ∀s1, s2 ∈ S ⇒[Φ is isomorphism ⇒ bijective] ∃r1, r2 ∈ R: Φ(r1) = s1, Φ(r2) = s2. Φ-1(s1s2) = Φ-1(Φ(r1)Φ(r2)) = Φ-1(Φ(r1r2)) =[Definition of an inverse mapping] r1r2 = Φ-1(s1)Φ-1(s2)

- ∀s1, s2 ∈ S ⇒[Φ is isomorphism ⇒ bijective] ∃r1, r2 ∈ R: Φ(r1) = s1, Φ(r2) = s2. Φ-1(s1+s2) = Φ-1(Φ(r1)+Φ(r2)) = Φ-1(Φ(r1+r2)) =[Definition of an inverse mapping] r1+r2 = Φ-1(s1)+Φ-1(s2)

- Φ-1(1S) =[Φ(1R) = 1S] 1R.

- By 1, 2 and 3, Φ-1 is a ring homomorphism, and since inverse of a bijective function Φ is bijective, Φ-1 is also bijective, hence Φ is a ring isomorphism.

- The kernel of a ring homomorphism Φ: R → S is an ideal in R.

Proof.

- The Kernel of a group homomorphism (a ring homomorphism is a group homomorphism) is a subgroup, (Ker(Φ), +) ≤ (R, +).

- Ker(Φ) is a subring of R. ∀x, y ∈ Ker(Φ) -Ker(Φ) ≤ R-, x -y ∈ Ker(Φ), x · y ∈ Ker(Φ)? Φ(x·y) = [Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(x)·Φ(y) = [x, y ∈ Ker(Φ)] 0·0 = 0 ⇒ x · y ∈ Ker(Φ)

- Ker(Φ) is an ideal of R. Let x ∈ Ker(Φ), r ∈ R, Φ(x·r) = [Φ is ring homomorphism] Φ(x)·Φ(r) = [x ∈ Ker(Φ)] 0·Φ(r) = 0 ⇒ x·r ∈ Ker(Φ) and similarly Φ(r.x) = 0, so r.x ∈ Ker(Φ).

- Let Φ: R → S be a ring homomorphism and let R'⊆ R be a subring of R ⇒ Φ(R') is a subring of S. In particular, Φ(R) is a subring of S.

- 1R ∈ R’ ⇒ 1S = Φ(1R) ∈ Φ(R’). This requirement depends on the definition of a ring.

- ∀s1, s2 ∈ Φ(R’) ⇒ ∃r1, r2 ∈ R’ such that Φ(r1) = s1 and Φ(r2) = s2. s1 - s2 = Φ(r1) - Φ(r2) =[Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(r1 - r2) ∈ Φ(R’) because R’ is a subring, r1 - r2 ∈ R'.

- ∀s1, s2 ∈ Φ(R’) ⇒ ∃r1, r2 ∈ R’ such that Φ(r1) = s1 and Φ(r2) = s2. s1 · s2 = Φ(r1)·Φ(r2) =[Φ is a ring homomorphism] Φ(r1·r2) ∈ Φ(R’) because R’ is a subring, r1 ·r2 ∈ R'.

Bibliography

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This post relies heavily on the following resources, specially on

NPTEL-NOC IITM, Introduction to Galois Theory, Michael Penn, and Contemporary Abstract Algebra, Joseph, A. Gallian.

- NPTEL-NOC IITM, Introduction to Galois Theory.

- Algebra, Second Edition, by Michael Artin.

- LibreTexts, Abstract and Geometric Algebra, Abstract Algebra: Theory and Applications (Judson).

- Field and Galois Theory, by Patrick Morandi. Springer.

- Michael Penn (Abstract Algebra), and MathMajor.

- Contemporary Abstract Algebra, Joseph, A. Gallian.

- Andrew Misseldine: College Algebra and Abstract Algebra.