|

|

|

|

|

|

“Why are there only two sexes? Are we not all created equal? Will homosexuals go to Hell? Do wives have to be submissive to their husbands?” the interviewer was not happy how the conversation was progressing, so he brought up the big guns and took the gloves off. “I will answer you,” the so called Jesus replied, “but first tell me, why men and not women are forced to go to war in the frontline. What is your definition of a woman? If a biological born man says that he or she truly feels like a woman, could he or she be exempt from going to war? Why women get sole custody of the kids most of the time? Are we not all created equal?” Apocalypse, Anawim, #justtothepoint.

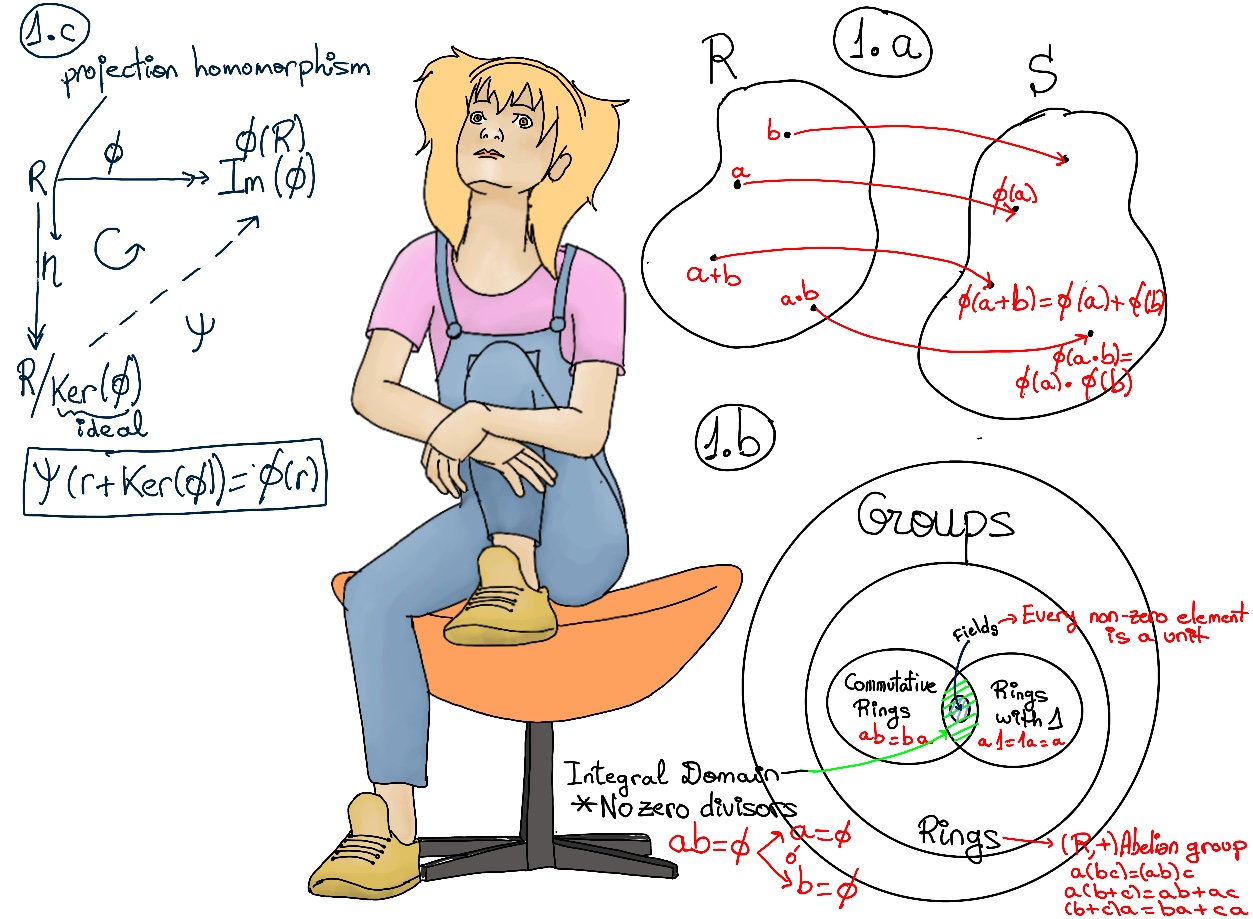

💍 A ring R is a non-empty set with two binary operations, addition (a + b) and multiplication (ab), such that ∀ a, b, c ∈ R:

Definition. A zero-divisor is an non-zero element a of a commutative ring R such that there exist a nonzero element in the ring, say b ∈ R with ab = 0, e.g., 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 10 are zero divisors in ℤ12, 4·3 =ℤ12 0, even though 4 and 3 are nonzero elements in ℤ12.

The existence os zero-divisors in a ring causes unusual results when one is finding zeros of polynomials with coefficients in the ring, e.g., x2 -4x + 3 = 0, we could find all its solutions by factoring it (x - 3)(x + 1), that is, 3, -1, but this does not work in ℤ12.

Zero divisors do not have inverses. Let R be a ring with identity and let a ∈ R. A multiplicative inverse of a is an element a-1∈ R such that a·a-1 = a-1·a = 1. An element which has a multiplicative inverse is called a unit, e.g., the units in ℤn are the elements of U(n), that is, the elements of ℤn which are relatively prime to n. In ℤ12, 1, 5, 7, and 11 are units.

A field is a commutative ring with unity in which every non-zero element is a unit. Examples: ℤ/nℤ with n prime, ℝ, ℂ, ℚ, but not ℤ because in general, n ∈ ℤ ⇏ 1/n ∈ ℤ. Figure 1.b.

Definition. An integral domain is a commutative ring with unity and no zero-divisors.Thus, a product of two elements a, b ∈ R is 0 (ab = 0) only when one of the factor is 0 (a = 0 ó b = 0).

Definition. The characteristic of a ring R, often denoted or written as char(R) or char R, is defined to be the smallest positive integer n such that nx = x+x··n times··+x = 0 ∀x ∈ R, where 0 is the additive identity. If no such integer exists, we say that R has characteristic 0.

Examples:

char(ℤ) = char(ℚ) = char(ℝ) = char(ℂ) = 0

ℤn has characteristic n because ∀a ∈ ℤn, a + a + ··n times·· + a = n·a = 0 ⇒ m = char(A) ≤ n. Suppose char(ℤn) = m, ∀x ∈ ℤn, m·x = 0. In particular, x = 1, m·1 = 1+1+··m times·· + 1 = 0 ⇒ m ≡ 0 (mod n) ⇒ n | m ⇒ n ≤ m ⇒[We have previously demonstrated that m = char(ℤn) ≤ n] n = m ⇒ char(ℤn) = n.

If R is a Boolean ring, then char(R) = 2. ∀x ∈ R, x + x =[∀r∈ R, r2=r] (x + x)2 = (x + x)(x + x) =[Distributive]x(x + x) + x(x + x) = x2 + x2 + x2 + x2 =[∀a∈ R, r2=r] 0. Therefore, ∀x ∈ R, x + x = 0.

Let X be a set, P(X) be its power set, which is the set of all subsets of the set X including the set itself and the empty set ∅. (P(X), ⊆) is a partially ordered set. Let A = {a, b, c}, and let P(A) be the power set of A (the set of all subsets of the set A), P(A) = {∅, {a}, {b}, {c}, {a, b}, {a, c}, {b, c}, {a, b, c}} P(X) is a commutative ring with unity (the unity of P(X) is the set X itself) with the following operations, A + B = (A ∪ B)\(A ∩ B) -the additional zero is the empty set ∅-, A·B = A ∩ B. (P(X), +, ·) is a Boolean ring ⇒[2A = A + A = (A ∪ A)\(A ∩ A) = ∅] Char(P(X)) = 2.

ℤ3[i] = {a + bi| a, b ∈ ℤ3} has characteristic 3 because ∀x ∈ ℤ3[i], 3x = 3(a+ bi) = a + bi + a + bi + a + bi = 3a + 3bi = 0.

ℤ2[x], the ring of all polynomials with coefficients in ℤ2 has characteristic 2.

Proposition. Let R be a ring with unity 1.

Proof.

There are two possibilities:

If 1 has infinite order under addition, then 1 + ··n times·· + 1 = n·1 ≠ 0, ∀n ∈ ℤ+, therefore char(R) = 0.

If 1 has order n under addition, then 1 + ··n times·· + 1 = n·1 = 0, and n is the least positive integer with this property.

∀x ∈ R, n·x = x + x + ··n times·· + x = 1·x + 1·x + ··n times·· + 1·x =[Distributivity property] (1 + ··n times·· + 1)·x =[By assumption, ord(1) = n] 0·x =[Property 1, rings] 0, therefore char(R) = n ∎

Examples:

Integral Multiple of Ring. Let (R, +, ○) be a ring. Let n·x be an integral multiple of x, $n·x = \begin{cases} 0_R, &n = 0 \\ x, &n = 1 \\ x+x+··_n··x, &n>1 \\ n·(-x), &n< 0 \end{cases}$

Then, ∀ x ∈ R: (m·x)○(n·x) = (m·n)·(x○x).

Proof: (Proof by induction)

Induction hypothesis, (m·x)○(k·x) = (m·k)·(x○x)

(m·x)○((k+1)·x) =[(k+1)·x = x + x + ··· k + 1 times ··· = (x + x + ··· k times ···+x) + x = k·x + x] (m·x)○(k·x + x) [Multiplication ○ is distributive with respect to addition] = (m·x)○(k·x) + (m·x)○x = [Hypothesis induction] (m·k)·(x○x) + (m·x)○x =[(m·x)○x = (x+··m·· + x)○x =Distributive (x○x+··m·· + x○x) = m·(x○x)] (m·k)·(x○x) + m·(x○x) = [(x○x +··m·k·· + x○x) + (x○x +··m·· + x○x) = (x○x +··m·k+m·· + x○x)] (m·k + m)·(x○x) =[m·k + m =-m and k are integer numbers- (m + ··k times·· + m) + m = m·(k+1)] (m·(k+1))·(x○x) ∎

Theorem. The characteristic of an integral domain D is either zero or a prime.

Proof.

Recall. An integral domain is a commutative ring with unity and no zero-divisors.

Let’s suppose 1 has order n, n·1 = 1+1+··n times+1+1 = 0, and n is not prime, but composite, that is, ∃s, t such that n = st, where 1 ≤ s, t ≤ n.

0 = n·1 = (s·t)·1 = (s·t)·(1○1) = [Integral Multiple of Ring Element, ∀ x ∈ R: (m·x)○(n·x) =Th previously demonstrated (m·n)·(x○x)] (s·1)○(t·1) ⇒ [D is an integral domain, no zero divisors]1 ≤ s, t ≤ n, s·1 = 0 ó t·1 = 0, and s is the least positive integer with the property that n·1 = 0 ⇒ s = n ó t = n ⊥, n is not prime.

Corollary. The characteristic of a field F is either zero or a prime

Proof. Every field is an integral domain.

Theorem. The characteristic of a finite ring R divides |R|.

Proof. R cannot have characteristic 0 because it is a finite field.

Let n = char(R), |R| = m, by the Lagrange’s theorem (the order of an element of a finite group divides the order of the group) implies that (additive notation) a + a + ··m times·· + a = ma = 0

The division algorithm, m = qn + r where 0 ≤ r < n ⇒ ra = (m -qn)a = ma -q(na) =[ma = 0, n = char(R)] 0 -q0 = 0, and n is the least positive integer making all nx = 0 ∀x ∈ R ⇒ r = 0 ⇒ m = qn ⇒ n | m = |R| ∎

Example. Let F be a field of order 2n, then char(F) = 2.

Recall the previous corollary. The characteristic of a field F is either zero or a prime However, F cannot have characteristic 0, because it is a finite field.

If F has characteristic p > 0, p is prime and p divides 2n ⇒ p = 2.