|

|

|

|

|

Definition. A topology on a set X is a collection $\mathbb{T}$ of subsets of X, called open sets, satisfying the following properties:

A pair (X, $\mathbb{T}$) consisting of a set X and a topology $\mathbb{T}$ is called a topological space. If q ∈ X, a neighborhood of q is an open set containing q.

Examples:

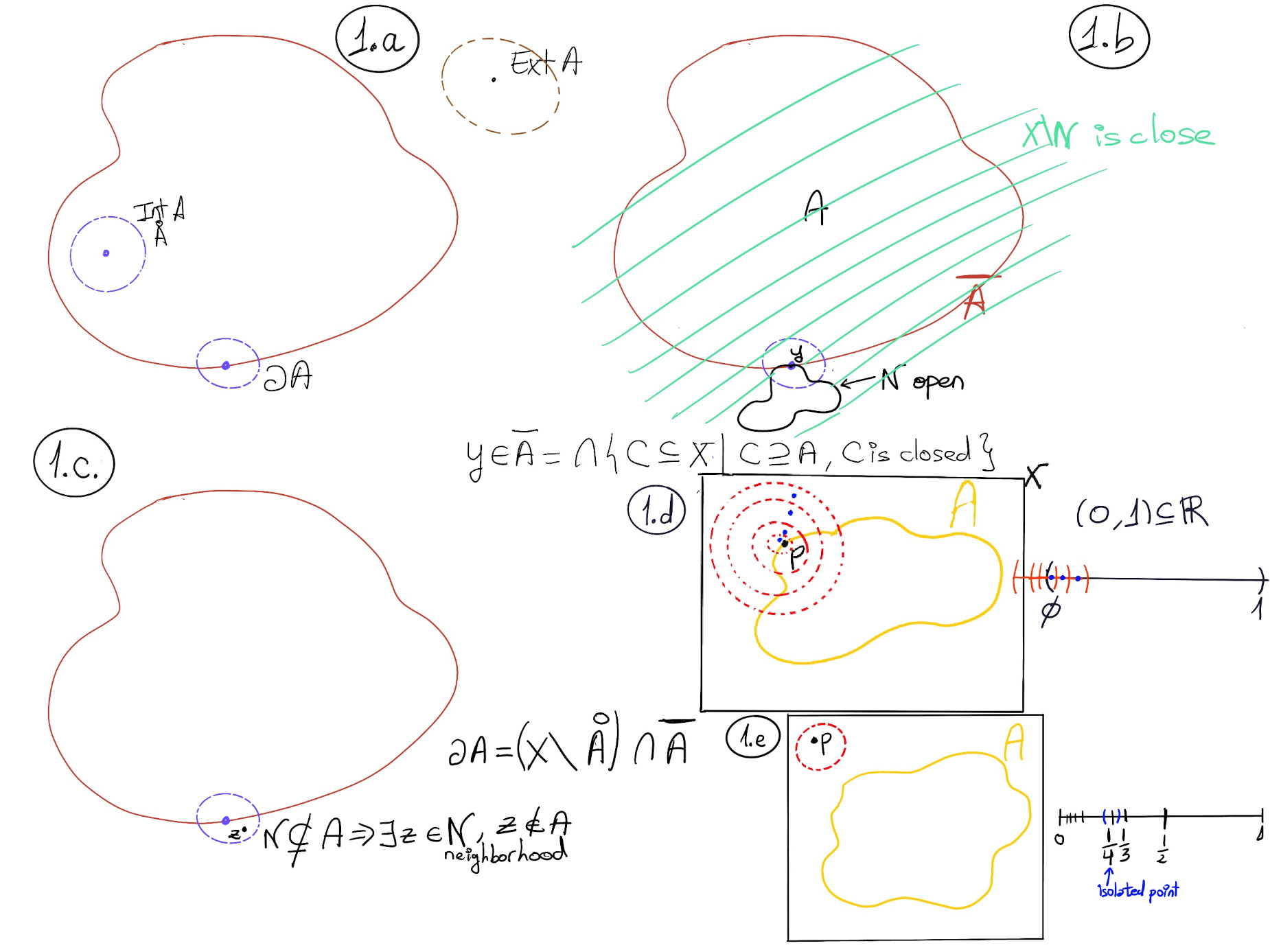

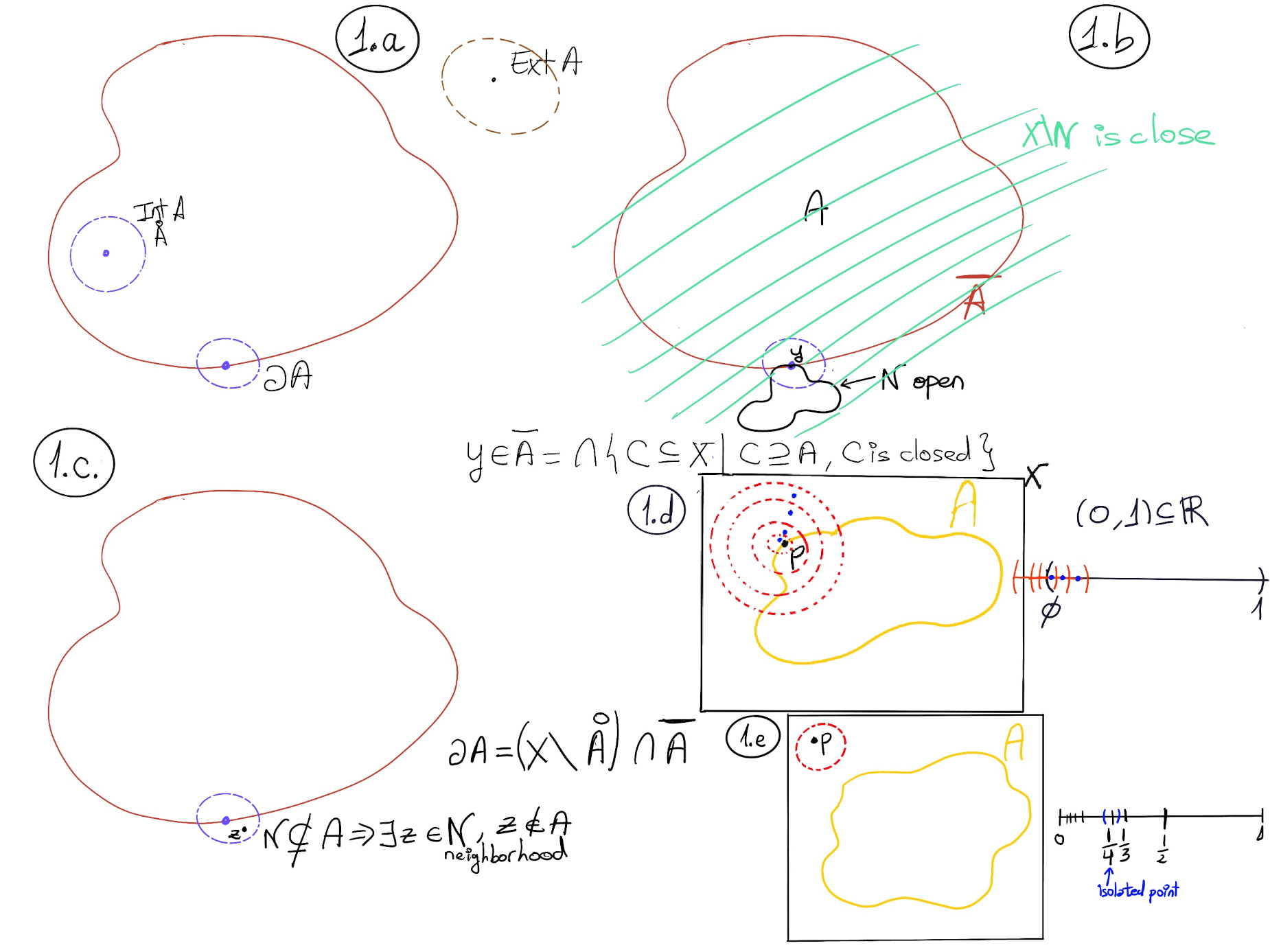

Let $\mathbb{T}$ be the collection of open sets in the usual metrical space sense, that is, a set A is open if ∀x ∈ A, ∃ε > 0: Bε(x) = {y ∈ M | d(x, y) < ε} ⊆ A (Figure 1.c.)

If M = ℝ, d = |x - y|, and we get the usual notion of open sets in the real line.

Notation. Unit interval, I ⊆ ℝ, I = [0, 1] = {x ∈ ℝ | 0 ≤ x ≤ 1}. Unit ball, $\mathbb{B}^n$ = {x ∈ ℝn| ||x|| < 1} = $\sqrt{x_1^2+···+x_n^2}$. Unit circle S1 ⊆ ℝ2, S1 = {x ∈ ℝ2: ||x|| = 1}. Unit n-sphere Sn ⊆ ℝn+1, Sn = {x ∈ ℝn+1: ||x|| = 1}, n = 2, this is basically the concept of an sphere.

Definition. A subset $\mathbb{F} ⊆ X$ of a topological space X is said to be closed if its complement X\$\mathbb{F}$ is open.

Some properties or consequences follow immediately:

Examples of closed sets:

y ∉ $\bar \mathbb{B}_r(x) =$ {y ∈ M: d(x, y) ≤ r} ⇒ d(x, y) > r ⇒ d(x, y) -r > 0, and we can take ε = d(x, y) -r.

Let’s take z ∈ Bε(x) (Figure 1.e) ⇒ d(x, z) + d(z, y) ≥ d(x, y) ⇒ [d(z, y) < ε, -d(z, y) > -ε] d(x, z) ≥ d(x, y) -d(z, y) > d(x, y) -ε = d(x, y) -(d(x, y) -r) = r. Therefore, d(x, z) > r ⇒ z ∉ $\bar \mathbb{B}_r(x)$

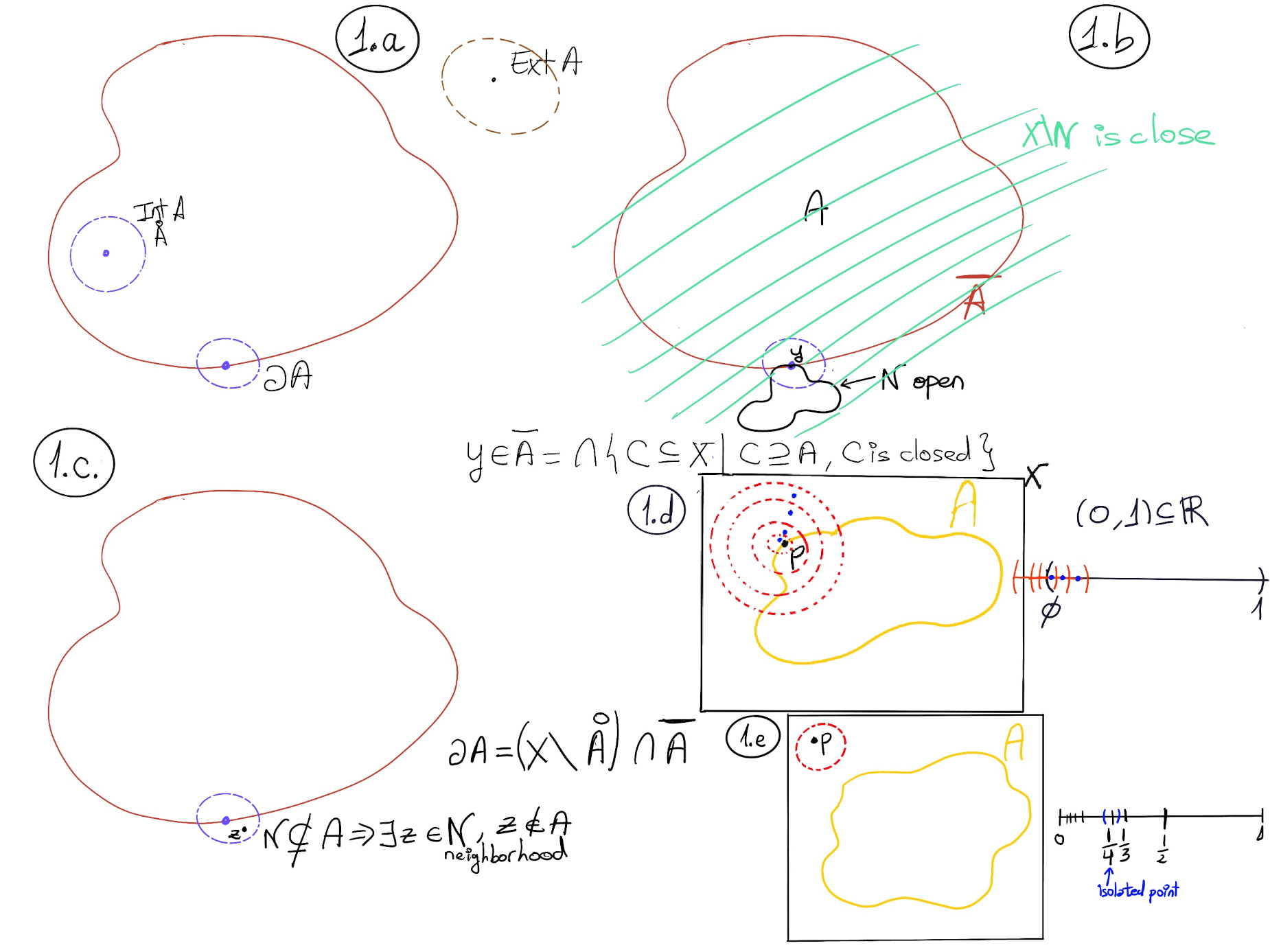

Definition. The closure of A in X, denoted by $\bar \mathbb{A}$ is the set $\bar \mathbb{A}=∩${B ⊆ X | B ⊇ A and B is closed} Figure 1.f. It is obvious that $\bar \mathbb{A}$ is closed, it is indeed the smallest closed set containing A.

The interior of A in X, denoted by Int A or $\mathring{A}$ is the set $\mathring{A}$ = ∪{C ⊆ X | C ⊆ A and C is open in X} Figure 1.g. It is also obvious that $\mathring{A}$ is open, it is indeed the largest open set contained in A.

The exterior of A, written Ext A, is X \ $\bar \mathbb{A}$, and the boundary of A written as ∂A, as ∂A = X\($\mathring{A}$ ∪ Ext A) Figure 1.h and 1.i.

Proposition. Let X be a topological space and A ⊆ X any subset.

Proof: y ∈ $\mathring{A}$ = ∪{B ⊆ X | B ⊆ A and B is open in A} ↭ ∃B ⊆ X, y ∈B, B ⊆ A, and B is open in A ↭ B is a neighborhood of y, contained in A

Proof. y ∈ $\bar \mathbb{A}=∩${C ⊆ X | C ⊇ A and C is closed} ↭ y ∈ C ∀C ⊆ X, C ⊇ A and C is closed.

Suppose ∃N, a neighborhood of y, open set, and N ∩ A = ∅ ⇒ X \ N is closed and X \ N ⊇ A and y ∉ X \ N (because y ∈ N) ⊥

Therefore, y ∈ C ∀C ⊆ X, C ⊇ A and C is closed ⇒ every neighborhood of y must contain a point of A.

Suppose that every neighborhood of y must contain a point of A ⇒ Suppose that ∃C ⊆ X, C ⊇ A and C is closed, but y ∉ C ⇒ X \ C is open, y ∈ X \ C, i.e. a neighborhood of y, and X \ C ∩ A = ∅ ⊥

Proof. y ∈ Ext A = X \ $\bar \mathbb{A}$ ↭ y ∉ $\bar \mathbb{A}$ ⇒ [A point y is in the closure of A ↭ every neighborhood of y contains a point of A] ↭ there exist a neighborhood of y contained in X \ A.

∂A = X\($\mathring{A}$ ∪ Ext A) = (X\$\mathring{A}$) ∩ (X\Ext A)) = (X\$\mathring{A}$) ∩ (X\X\$\bar \mathbb{A}$) = (X\$\mathring{A}$) ∩ $\bar \mathbb{A}$

Let’s assume y ∈ ∂A, and let N be a neighborhood of y. y ∈ (X\$\mathring{A}$) ⇒ y ∉ $\mathring{A}$ ⇒ [A point y is in the interior of A ↭ y has a neighborhood contained in A] there is no neighborhood contained in A, in particular N is not contained in A ⇒ ∃z ∈ N, z ∉ A.

On the other hand, y ∈ $\bar \mathbb{A}$ ⇒ [A point y is in the closure of A ↭ every neighborhood of y contains a point of A] ∃z’∈ N, z ∈ A. The converse statement is proved by tracing back through the above argument.

Let’s prove $\bar \mathbb{A} = \mathring{A} ∪ ∂A$.

x ∈ $\mathring{A} ∪ ∂A$ ⇒ x ∈ $\mathring{A}~ or~ x ∈ ∂A$

Case 1: $x ∈ \mathring{A}$ = ∪{C ⊆ X | C ⊆ A and C is open in X} ⇒ x ∈ $\bar \mathbb{A}$

Case 2: x ∈ ∂A. Suppose x is not in some closed set B, B ⊇ A ⇒ x ∈ (X\B), (X\B) open set, A ∩ (X\B) = ∅ ⊥ since every neighborhood of x (x ∈ ∂A) must contain elements in A and X\A. Therefore, $\mathring{A} ∪ ∂A⊆\bar \mathbb{A}$.

Let x ∈ $\bar \mathbb{A}$ and suppose x is an exterior point of A ⇒ It has a neighborhood contained in X \ A, so there is a neighborhood of x which entirely avoids A ⊥ (A point y is in the closure of A ↭ every neighborhood of y contains a point of A)

The interior, boundary, and exterior of a set A together partition the whole space into three blocks: A = $\mathring{A}∪Ext~ A ∪ ∂A$ ⇒ x ∈ $\mathring{A}∪ ∂A$. Therefore, $\bar \mathbb{A}⊆\mathring{A} ∪ ∂A$.

The exterior is the complement of a closed set $\bar \mathbb{A}$, so it is open. The boundary is the complement of the union of two open sets $\bar \mathbb{A}$ and Ext A, so it is closed.

Proof.

Let’s prove that A is open ⇒ $A = \mathring{A}$

Reclaim that $A = \mathring{A}$ = ∪{C ⊆ X | C ⊆ A and C is open in X}

Let’s suppose that A is a open set, then A ⊆ A and A is open in X ⇒ A ⊆ ∪{C ⊆ X | C ⊆ A and C is open in X} = $\mathring{A}$, but ∪{C ⊆ X | C ⊆ A and C is open in X} = $\mathring{A} ⊆ A$ because it is a union of sets that they are all contained in A.

A is open ⇐ $A = \mathring{A}$

If $A = \mathring{A}$, then we know that as $\mathring{A}$ is open, then A is open, too.

$A = \mathring{A}$ ⇒ A contains none of its boundary points.

$A = \mathring{A}$ ⇒ ∂A = X\($\mathring{A}$ ∪ Ext A) = X\(A ∪ Ext A) ⇒ A contains none of its boundary points.

$A = \mathring{A}$ ⇐ A contains none of its boundary points.

Suppose A contains none of its boundary points, i.e., A ∩ ∂A = ∅, we claim $A = \mathring{A}$. We already know that $\mathring{A} ⊆ A$, so we need to prove that $A ⊆ \mathring{A}$, i.e., ∀a ∈ A, y has a neighborhood completely contained in A.

Let’s assume for the sake of contradiction that ∃ a ∈ A, ∀ neighborhood U of a, U ⊊ A ⇒ ∃ b ∈ U, b ∈ X \ A ⇒ Every neighborhood of a contains both a point of A (a ∈ A) and a point b ∈ X \ A ⇒ a ∈ ∂A ⊥ (we have assume that A and ∂A are disjoint)

Introduction to Topological Manifolds, Lee