|

|

|

|

|

Perfect is the enemy of the good.

No pressure, no diamonds, Thomas Carlyle.

For every problem there is always, at least, a solution which seems quite plausible and reasonable. It is simple and clean, direct, neat, and very nice, and yet it is wrong, #Anawim, justtothepoint.com

Lagrange’s Theorem. Let G be a finite group and let H be a subgroup of G. Then, the order of H is a divisor of the order of G, .i.e., |H| | (divides) |G| or, more precisely, |G| = |H| · |[G:H]|.

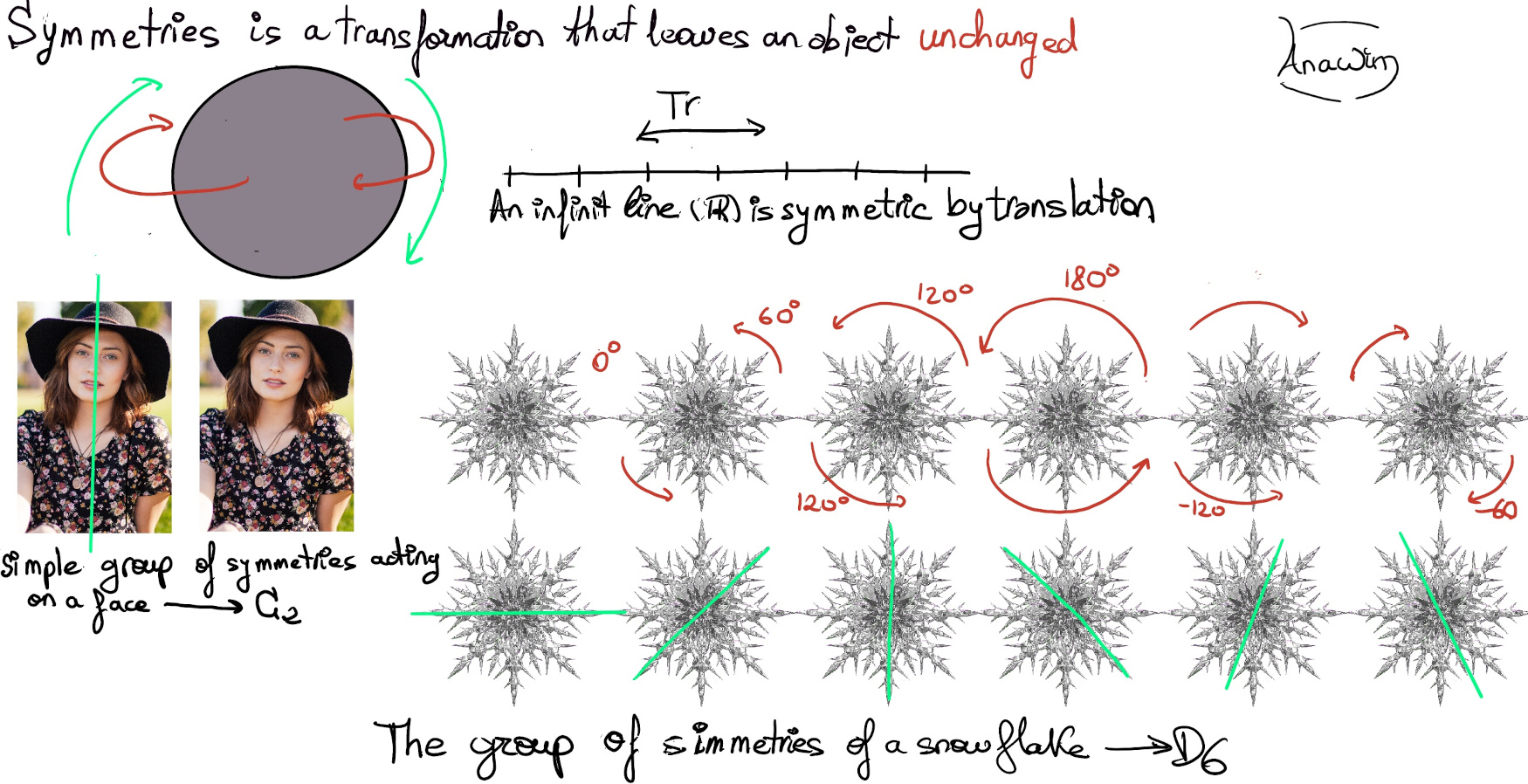

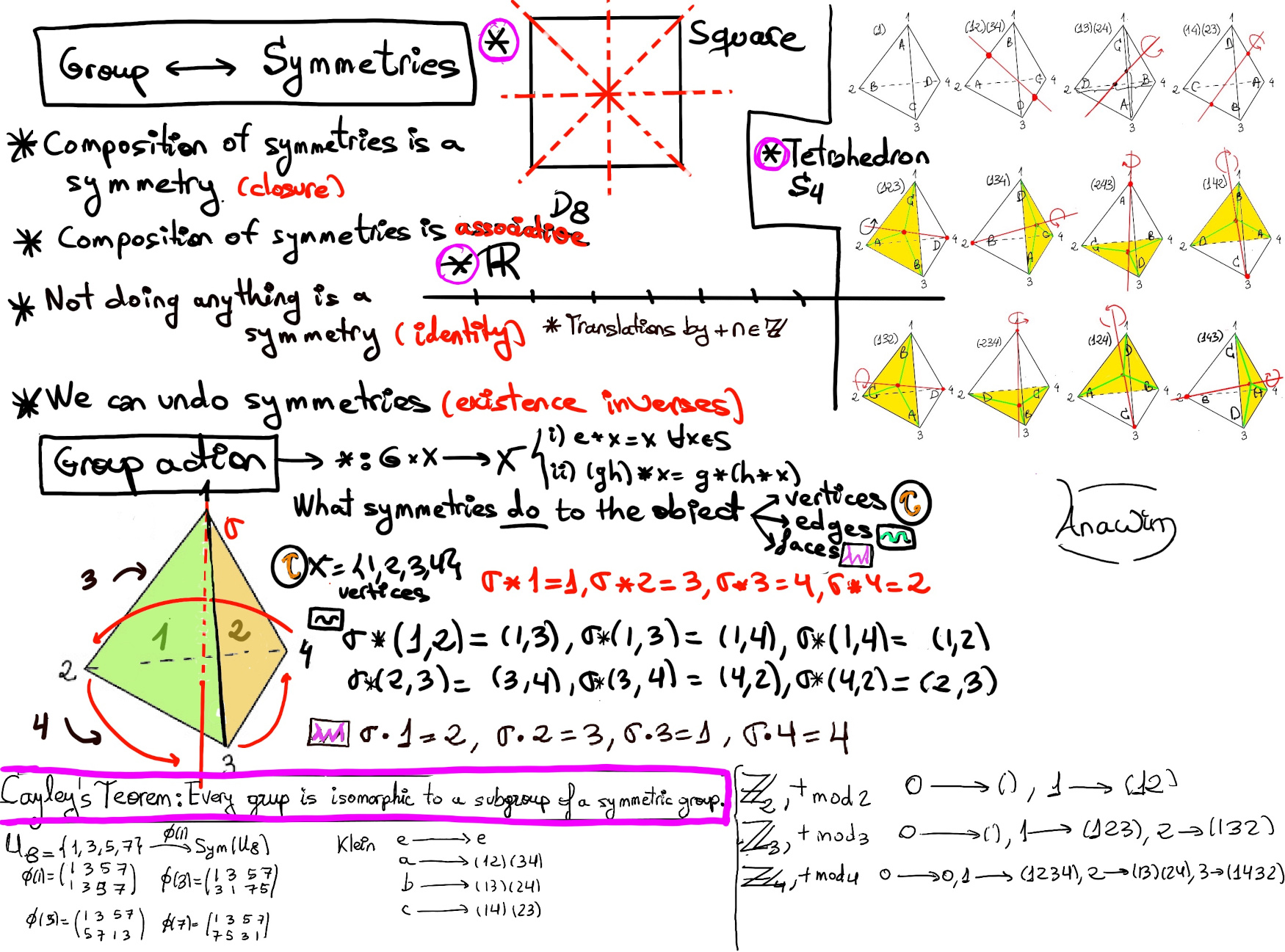

A (left) group action is an operation Φ: G x X → X such that ∀(g, x) ∈ G x X: g*x = Φ(g, x) ∈ X. It satisfies that ∀g, h ∈ G, x ∈ X: g * (h * x) = (g * h) * x, and ∀x ∈ X: e * x = x. The group G thus acts on the set X.

There is a one-to-one correspondence between group actions of G on X and permutation representations of G in X as follows. Let Φ: G x X → X be a group action and ρ: G → Sx be a permutation representation (a homomorphism from G to the symmetric group of X). The following are equivalent:

Definition. Let G be a group of permutations of a set S, and s ∈ S. The orbit of s under G, orbG(s), is the subset of S defined as {Φ(s): Φ ∈ G}. It is basically everything that can be reached from s by a permutation of G.

The stabilizer of s in G, stabG(s), is the subset of permutations which don't move s when they act on it, stabG(s) = {Φ ∈ G| Φ(s)=s}

Alternative Definitions. Let an arbitrary group G act on a set S. For each s ∈ S, its orbit is orbG(s) = {g·s : g ∈ G} ⊆ X and its stabilizer is stabG(s) = {g ∈ G: g·s = s} ⊆ G. The orbit is the set of places where a point can be moved by the group action. The stabilizer is the set of group elements that fix a given point.

Proposition. Let an arbitrary group G act on a set S. stabG(x) = {g ∈ G| g·x = x} is a subgroup of G.

Proof.

Examples:

(i) $(\begin{smallmatrix}1 & 0\\ 0 & 1\end{smallmatrix})·(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ y\end{smallmatrix}) =(\begin

{smallmatrix}x\\ y\end{smallmatrix})$

(ii) $A·(B·(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ y\end{smallmatrix})) = (AB)·(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ y\end{smallmatrix})$ by the associative law of matrix multiplication.

orbG(0) = {0} since A·0 = 0 ∀A ∈ GL2(ℝ), and stabG(0) = GL2(ℝ). orbG$(\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ = ℝ2 - $(\begin{smallmatrix}0\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ because if $(\begin{smallmatrix}a\\ b\end{smallmatrix})$ ≠ 0, then $(\begin{smallmatrix}a\\ b\end{smallmatrix}) = (\begin{smallmatrix}a & 1\\ b & 0\end{smallmatrix}) (\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ and stabG$(\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ = {$(\begin{smallmatrix}1 & x\\ 0 & y\end{smallmatrix})$ : y ≠ 0} ⊆ GL2(ℝ) because $(\begin{smallmatrix}1 & x\\ 0 & y\end{smallmatrix})·(\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})=(\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$

However, orbG$(\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ ≠ ℤ2 - {0}. The reason is that a matrix $(\begin{smallmatrix}a & b\\ c & d\end{smallmatrix})$ sends $(\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ to $(\begin{smallmatrix}a\\ c\end{smallmatrix})$, which is a vector with relatively prime coordinates since ad -bc = ± 1. Conversely, each vector $(\begin{smallmatrix}m\\ n\end{smallmatrix})$ with relatively prime coordinates is in the orbit of $(\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ because ∃x, y∈ ℤ: mx + ny = 1, so $(\begin{smallmatrix}m & -y\\ n & x\end{smallmatrix})$ ∈ GL2(ℤ) -its determinant is 1- and $(\begin{smallmatrix}m & -y\\ n & x\end{smallmatrix})(\begin{smallmatrix}1\\ 0\end{smallmatrix}) = (\begin{smallmatrix}m\\ n\end{smallmatrix})$

$orb_G(\begin{smallmatrix}0\\ 0\end{smallmatrix}) = {(\begin{smallmatrix}0\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})}, stab_G(\begin{smallmatrix}0\\ 0\end{smallmatrix}) = G$

x, y ≠ 0 and x ≠ y, $orb_G(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ y\end{smallmatrix})$ = {$(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ y\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ -y\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}-x\\ y\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}-x\\ -y\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}y\\ x\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}-y\\ x\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}-y\\ -x\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}y\\ -x\end{smallmatrix})$}

y ≠ 0, $orb_G(\begin{smallmatrix}0\\ y\end{smallmatrix}) = orb_G(\begin{smallmatrix}y\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ = { $(\begin{smallmatrix}0\\ y\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}0\\ -y\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}-y\\ 0\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}y\\ 0\end{smallmatrix})$ }

x ≠ 0, $orb_G(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ x\end{smallmatrix}) $ = { $(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ x\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}-x\\ -x\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ -x\end{smallmatrix}), (\begin{smallmatrix}-x\\ x\end{smallmatrix})$ }

y≠0, $stab_G(\begin{smallmatrix}0\\ y\end{smallmatrix}) = ${$(\begin{smallmatrix}1 & 0\\ 0 & 1\end{smallmatrix}),(\begin{smallmatrix}-1 & 0\\ 0 & 1\end{smallmatrix})$} where y ≠ 0

x≠0, $stab_G(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ 0\end{smallmatrix}) = (\begin{smallmatrix}1 & 0\\ 0 & 1\end{smallmatrix}),(\begin{smallmatrix}1 & 0\\ 0 & -1\end{smallmatrix})$ where y ≠ 0

x≠0, $stab_G(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ x\end{smallmatrix}) = (\begin{smallmatrix}1 & 0\\ 0 & 1\end{smallmatrix}),(\begin{smallmatrix}0 & 1\\ 1 & 0\end{smallmatrix})$ where y ≠ 0

x, y ≠ 0, x ≠ y, $stab_G(\begin{smallmatrix}x\\ y\end{smallmatrix}) = ${e}

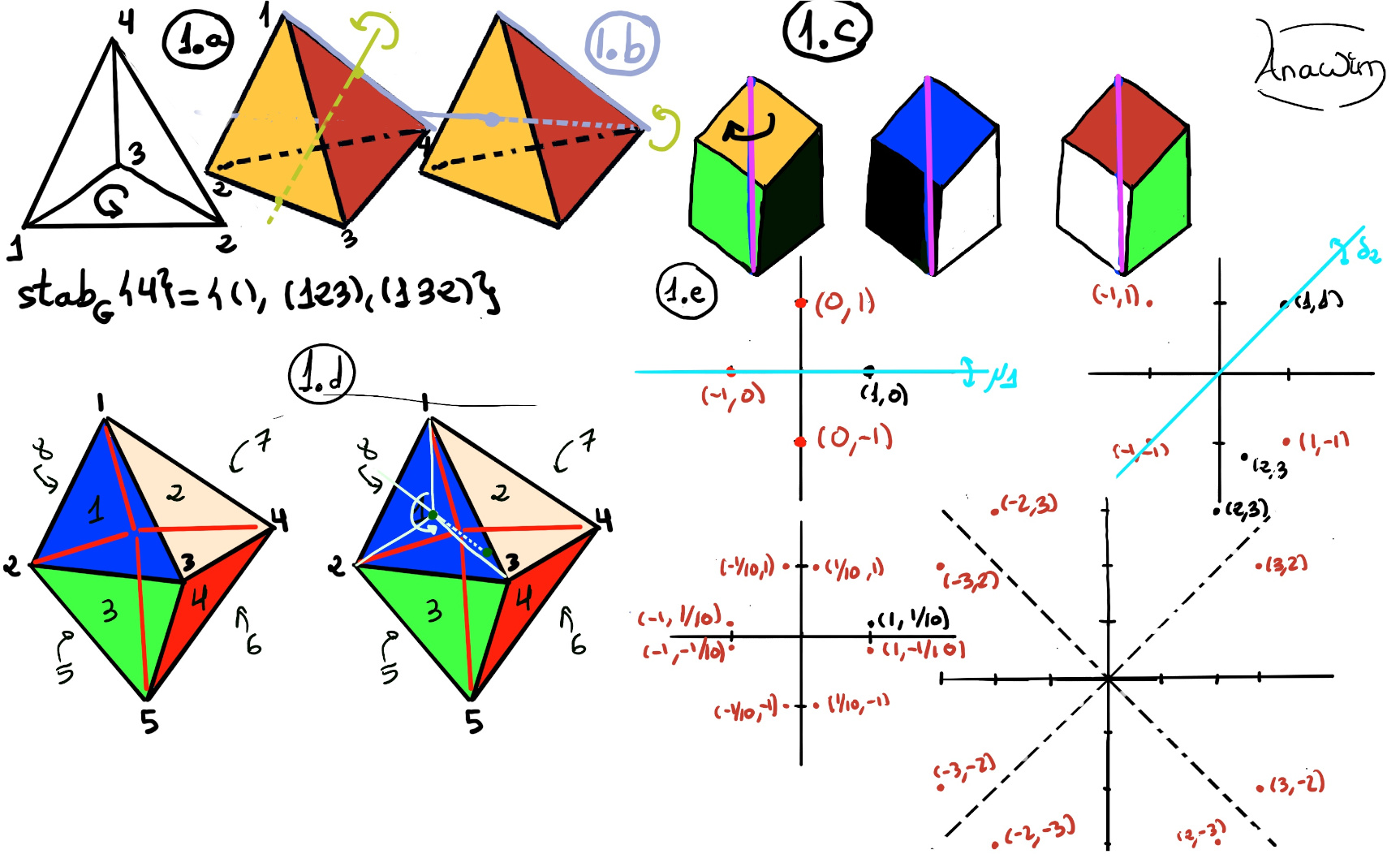

stabS4(4) = {(), (12), (13), (23), (123), (132)} ≋ S3, i.e., A permutation of S4 = {1, 2, 3, 4} that fixes the element 4 is basically the same as a permutation of {1, 2, 3}. stabS4(2) = {(), (13), (14), (34), (134), (143)} [It is the permutation of {1, 3, 4} (with 2 fixed)] ≋ S3.

∀i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4}, orbS4(4) = {1, 2, 3, 4}. Then, ∀i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4}, |orbS4(i)|·|stabS4(i)| = |{1, 2, 3, 4}|·|S3| = 4·6 = 24 = |S4|, so the orbit-stabilizer theorem is confirmed.

For n ≥ 2, consider Sn in its natural action on {1, 2, . . . , n}. What is the stabilizer of an integer i ∈ {1, 2, . . . , n}? It is the set of permutations of {1, 2, . . . , n} fixing i, which can be thought of as the set of permutations of {1, 2, . . . , n} − {i}. This is an isomorphic copy of Sn-1 inside Sn (once we identify or rename {1, 2, . . . , n} − {i} with the numbers from 1 to n − 1). Therefore, the stabilizer of each number in {1, 2, . . . , n} for the natural action of Sn on {1, 2, . . . , n} is isomorphic to Sn-1. Any of the n objects can be mapped to any other under an element in Sn, hence |Sn| = |stabSn(i)|·|orbSn(i)| = |Sn-1|·n = (n-1)!·n = n!, so the orbit-stabilizer theorem is, once again, confirmed.

orbG(1) = {1, 2, 3}. orbG(2) = {2, 1, 3}. orbG(4) = {4, 6, 5}. orbG(7) = {7, 8}.

(1):1 → 1, (132)(465)(78): 1 → 3, (132)(465): 1 → 3, (123)(456):1 → 2 [···] orbG(1) = {1, 2, 3}

stabG(1) = {(1), (78)}. stabG(2) = {(1), (78)}. stabG(4) = {(1), (78)}. stabG(7) = {(1), (132)(465), (123)(456)}.

Then again, |stabG(1)| * |orbG(1)| = |{(1), (78)}| * |{1, 2, 3}| = 2 * 3 = 6 = |G| = |{(1), (132)(465)(78), (132)(465), (123)(456), (123)(456)(78), (78)}|

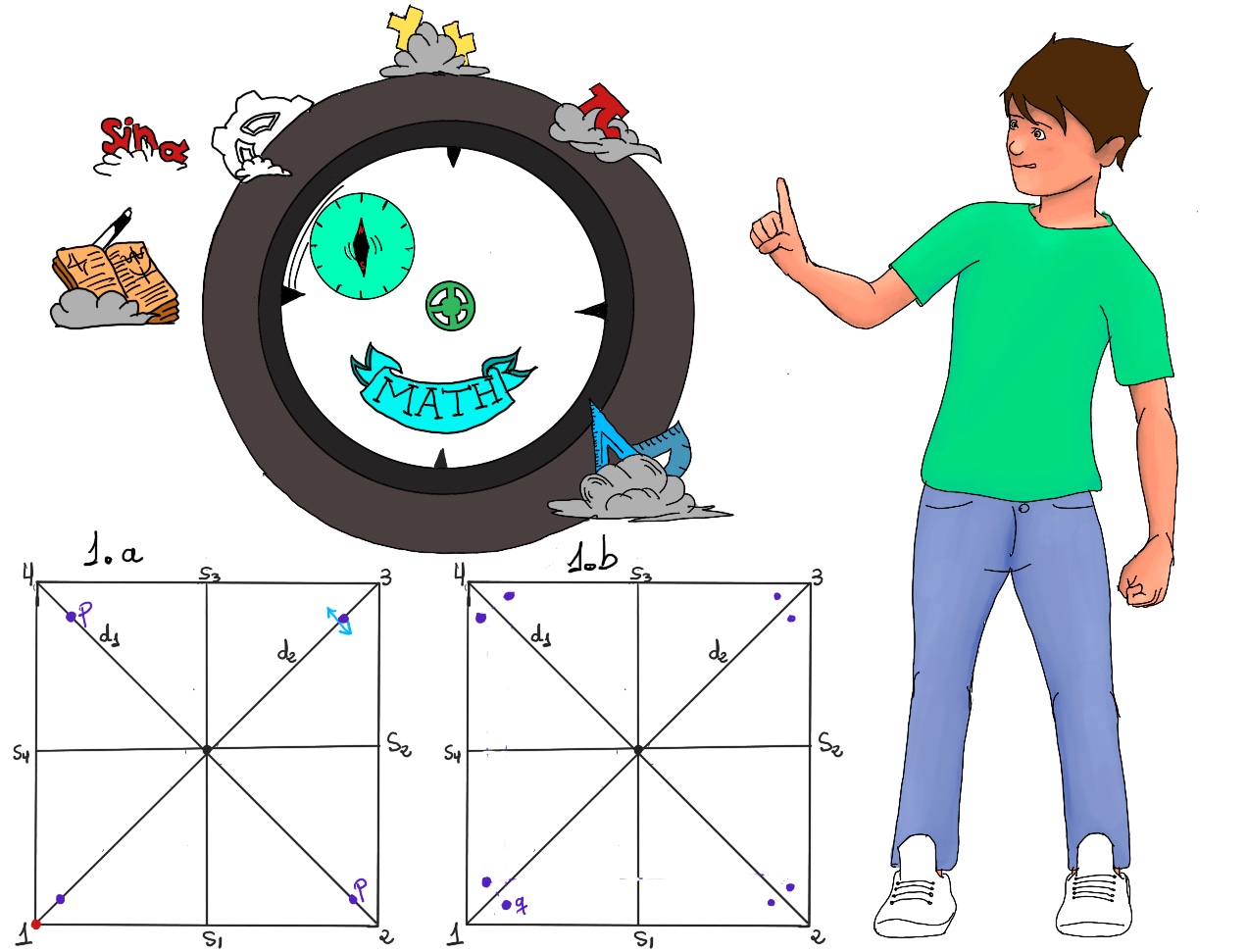

stabD4(1) = {e (=ρ0), δ2}. stabD4(s3) = {e (=ρ0), μ2}. stabD4(d1) = {e (=ρ0), δ1, ρ2, δ2}. stabD4(p) = {e (=ρ0), δ1}. stabD4(q) = {e (=ρ0)}.

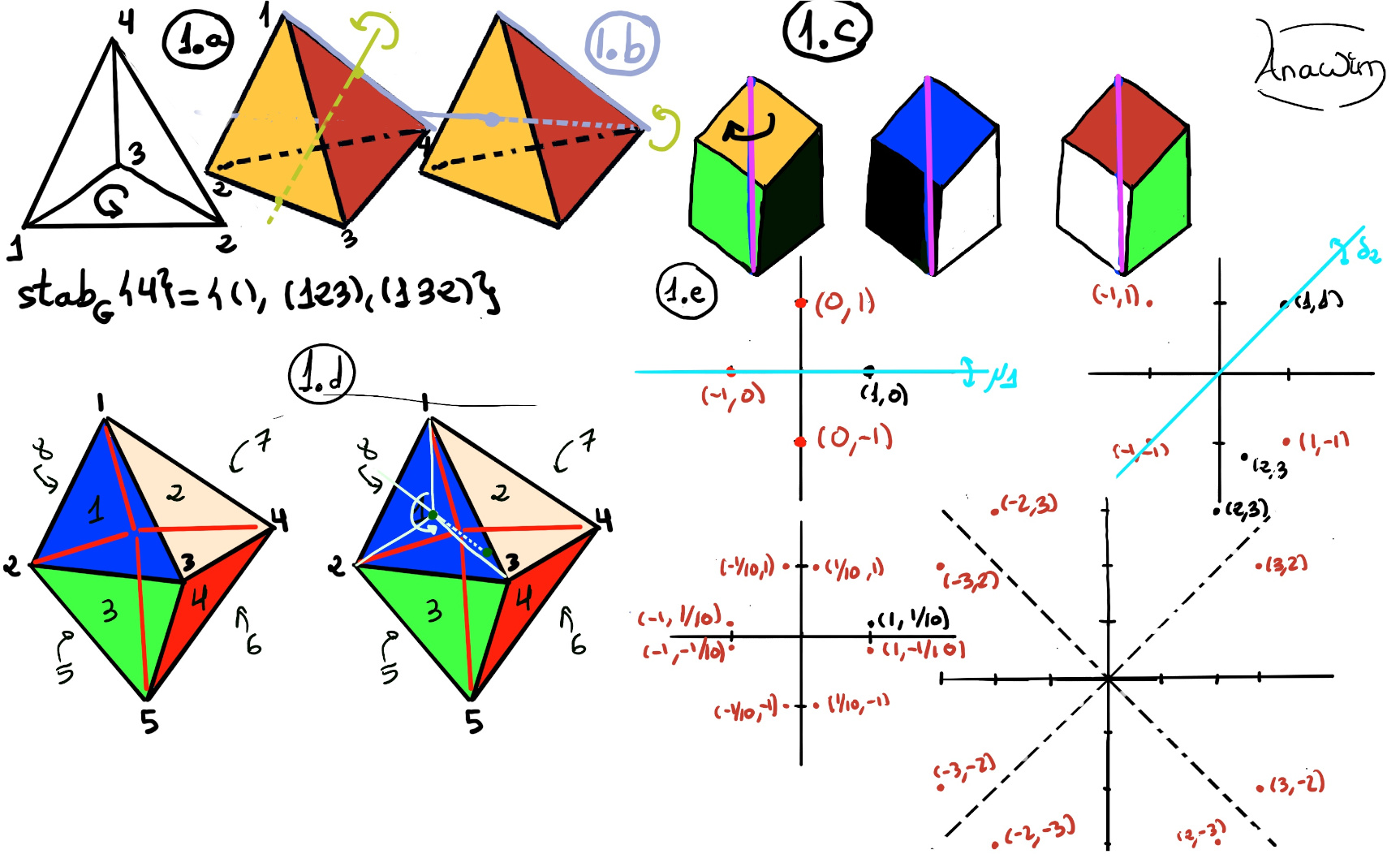

Figure 1.a and Fig 1.b illustrates the orbit of the points p, q under D4 (left -p- and right -q-) respectively.

Let’s complete the following chart for different points of ℝ2 (1.e):

| (x,y) | orbitD4(x, y) | stabD4(x, y) | # orbit | # stabilizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0,0) | (0, 0) | D4 | 1 | 8 |

| (1, 0) | (1, 0), (0, 1), (-1, 0), (0, -1) | e, μ1 | 4 | 2 |

| (1, 1) | (1, 1), (-1, 1), (1, -1), (-1, -1) | e, δ2 | 4 | 2 |

| (1, 1/10) | (1, 1/10), (1, -1/10), (-1, 1/10), (-1, -1/10), (-1/10, 1), (1/10, 1), (-1/10, -1), (1/10, -1) | e | 8 | 1 |

| (2, 3) | (2, 3), (3, 2), (-2, 3), (-3, 2), (2, -3), (3, -2), (-2, -3), (-3, -2) | e | 8 | 1 |

The number of elements in the orbit times the number of elements in the stabilizer is always the same, it is always 8, for each point, so the orbit-stabilizer theorem is confirmed.

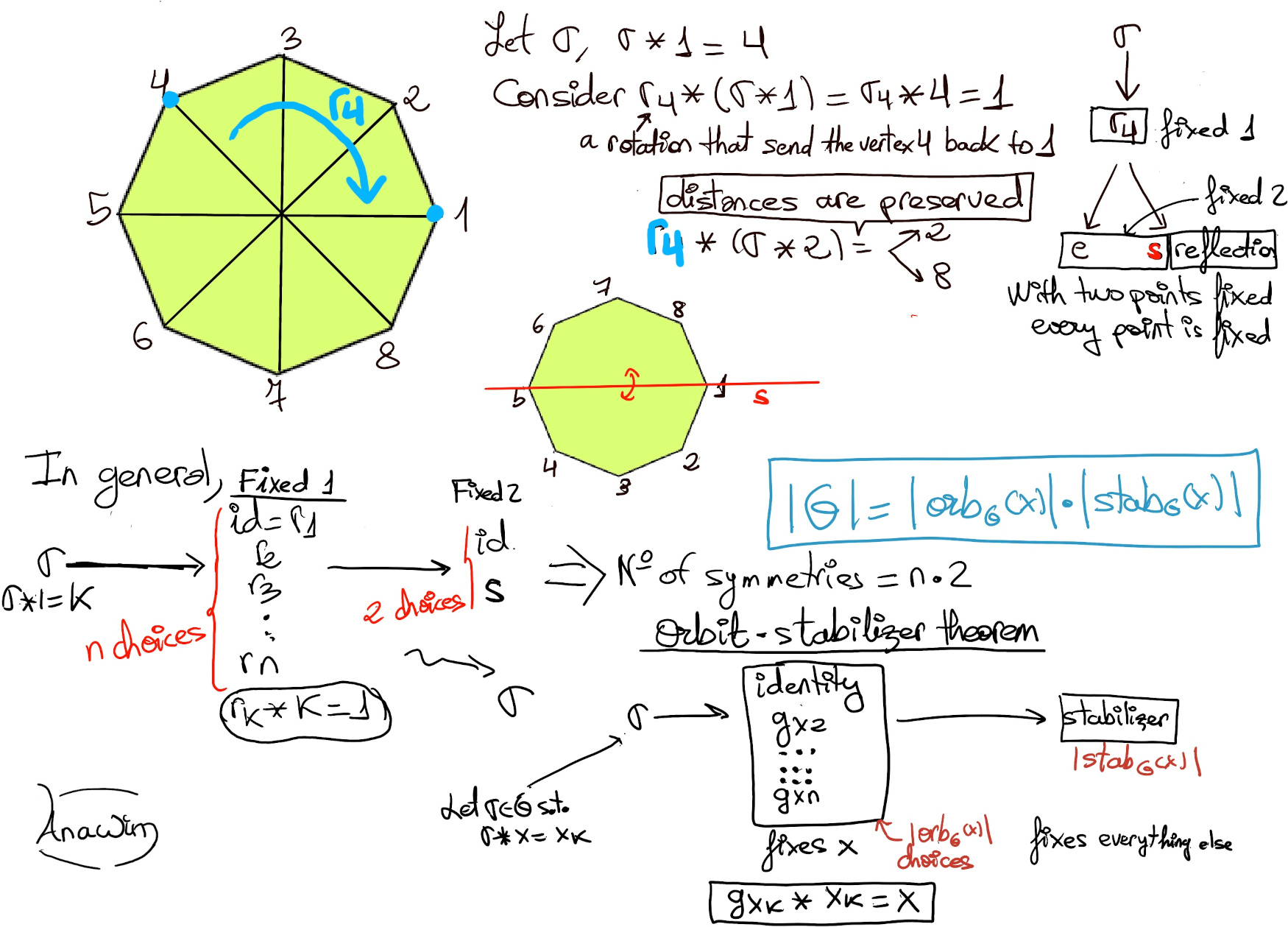

Orbit-Stabilizer Theorem. Let G be a finite group of permutations of a set S. Then, ∀i ∈ S, |orbG(i)| = [G: stabG(i)] = $\frac{|G|}{|stab(i)|}$ or, alternatively, |G| = |orbG(i)||stabG(i)|

An alternative formulation is as follows. Let G be a group which acts on a finite set S. Then, ∀i ∈ S, |orbG(i)| = [G: stabG(i)] = $\frac{|G|}{|stab(i)|}$ or, alternatively, |G| = |orbG(i)||stabG(i)|

Proof.

stabG(i) is a subgroup of G, so by Lagrange’s Theorem, |G|/|stabG(i)| = [G : stabG(i)] is the number of distinct left (or right) cosets of stabG(i) in G.

We claim that |orbG(i)| = [G : stabG(i)], that is, the number of distinct left (or right) cosets of stabG(i) in G. We are going to do this by defining a bijection between both sets.

Let T be the mapping T: G/stabG(i) → orbG(i), defined as follows, ∀Φ ∈ G, ΦstabG(i) = Φ(i).

αstabG(i) = βstabG(i) ⇒[aH = bH ↭ a-1b ∈ H] α-1β ∈ stabG(i) ⇒[By definition of stabilizer] α-1β(i) = i ⇒ α(α-1β(i)) = α(i) ⇒ β(i) = α(i).

is T one-to-one? Suppose T(αstabG(i)) = T(βstabG(i)) ⇒ α(i) = β(i) ⇒ α-1β(i) = i ⇒ α-1β ∈ stabG(i) ⇒[aH = bH ↭ a-1b ∈ H] αstabG(i) = βstabG(i)

is T onto? Let j ∈ orbG(i) ⇒ ∃α ∈ orbG(i): α(i) = j, and therefore T(αstabG(i)) = α(i) = j ∎

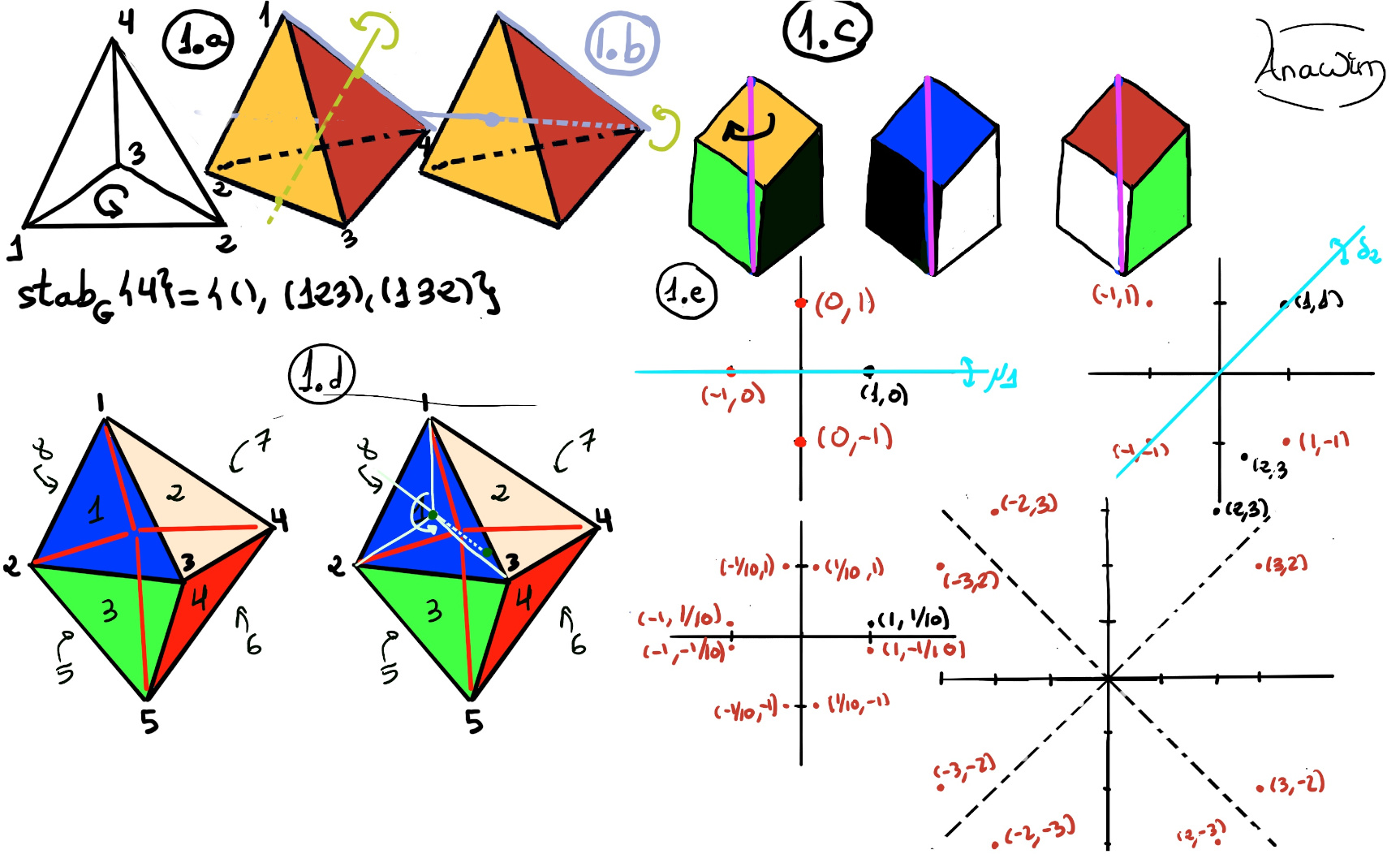

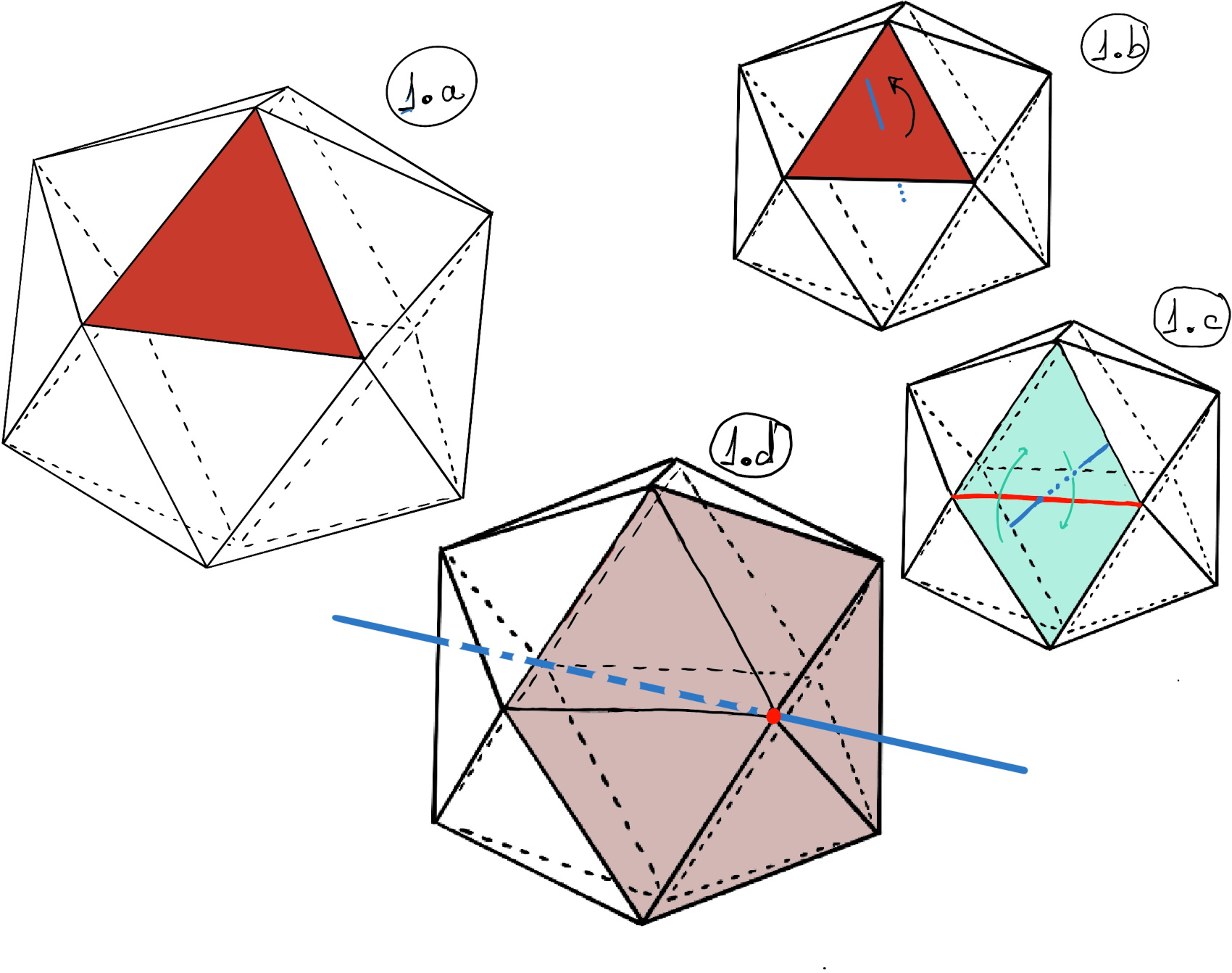

Exercises. Each platonic solid has a rotational symmetry group which acts naturally on the solid.

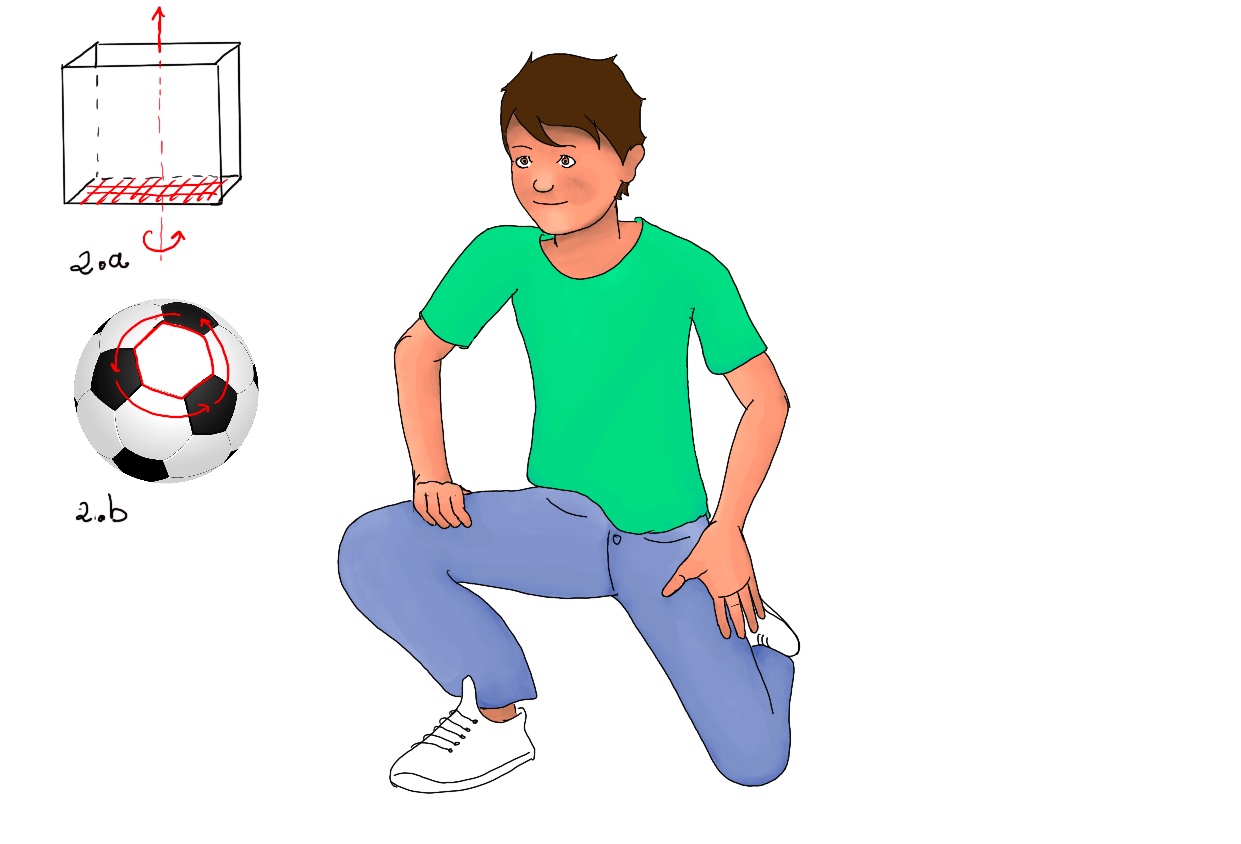

|orbG(1)| = 6, i.e., there are six rotations that carries face number 1 to any other face. Futhermore, |stabG(1)| = 4, that is, there are four rotations (0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°) about the line perpendicular to the face and passing through its center that leave face number 1 where it is or fixed (Figure 2.a)

Finally, we are able to calculate how many rotations a cube has. By the Orbit-Stabilizer Theorem, |G| = |orbG(1)||stabG(1)| = 6 x 4 = 24.

There are 24 symmetries. A cube has six faces (1, 2,…, 6) any of which can be moved to the bottom, and this face can be rotated into four different positions, so therefore 6 x 4 = 24.

| Action | #orbitG | #stabG | ord(G) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| on faces | 6 | 4 | 24 | |

| on edges | 12 | 2 | 24 | |

| on vertices | 8 | 3 | 24 |

As for a vertex x, orbG(x) = 8 because there exists a symmetry such that a specific vertex can get mapped to any of the other. Consider rotating a cube about its longest diagonal axis, there are three faces that are permuted cyclically (in Figure 1.c., red, yellow, and blue are an orbit of three; and the black, white, and green are another). The stabilizer of the vertex consists of the identity 2π, rotation along the long diagonal axis by 2π/3, and the same rotation by 4π/3

A tetrahedron is a pyramid with a triangular base. It has 4 vertices, 6 edges, and 4 faces. Clearly any vertex can be rotated to any other, orbG(v1) = {v1, v2, v3, v4} The stabilizer of the vertex 1 is the group of rotations keeping it fixed. It consists of the identity e, and (234), and (243) (Figure 1.a.). Any rotational axis going through a vertex and the centre of gravity must go through the centre of the opposite face which is an equilateral and the angle of rotation that leaves the vertex invariant is 2π/3. G = {I, (123), (124), (132), (134), (143), (124), (234), (243), (12)(34), (13)(24), (14)(23)}

The edge |orbG(23)| = 6, and |stabG(23)| = 2, the identity and the axe joining the midpoint of (23) and (14), that is “e” and “(14)(23)”.

| Action | #orbitG | #stabG | ord(G) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| on faces | 4 | 3 | 12 | |

| on edges | 6 | 2 (Figure 1.b) | 12 | |

| on vertices | 4 | 3 | 12 |

The group of rotational symmetries in ℝ3 leaving the tetrahedron invariant are: the identity, I (= 1); two rotations through 120° and 240° about each of the four axes joining vertices with centres of opposite faces (= 1 + 2*4); and one rotation through angle 180° about each of the three axes joining the midpoints of opposites edges. (= 1 + 2*4 + 3 = 12)

Any face can go to any face, and there are three rotational symmetries that fix the face 1; one is the identity, a second one is σ = (238)(457) -it permutes the three vertices of face 1, soits axis must be the line through the center of that particular face and the center of the octahedron (1.d); and the last one is σ2 = σ-1

| Action | #orbitG | #stabG | ord(G) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| on faces | 8 | 3 | 24 | |

| on edges | 12 | 2 | 24 | |

| on vertices | 6 | 4 | 24 |

| Action | #orbitG | #stabG | ord(G) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| on faces | 20 | 3 | 60 | |

| on edges | 30 | 2 (Figure 1.c) | 60 | |

| on vertices | 12 | 5 (Figure 1.d) | 60 |

A soccer ball is a set of 20 faces that are regular hexagons and 12 faces that are regular pentagons. Let’s view each rotation in G as a permutation of the 12 pentagons. Since any pentagon can be moved to any other pentagon by some rotation, |orbG(1)| = 12. Besides, there are five rotations that fix or stabilize any particular pentagon. Thus, by the Orbit-Stabilizer Theorem, |G| = |orbG(1)||stabG(1)| = 12 x 5 = 60.

Let’s view each rotation in G as a permutation of the 20 hexagons. Since any hexagon can be carried to any other hexagon by some rotation, |orbG(1)| = 20. Besides, there are three rotations that fix or stabilize any particular hexagon.

Notice that the six sides of one of the hexagons are not all equal, three of them border on pentagons and three of them border on hexagons. There are not six valid rotations, but only three. Indeed, the other three rotations do not map pentagons to pentagons, and hence aren’t symmetries of the soccer ball (Figure 2.b).

Thus, by the Orbit-Stabilizer Theorem, |G| = |orbG(1)||stabG(1)| = 20 x 3 = 60.