|

|

|

|

|

|

The odoriferous fumes being emitted from the vast depths of your cavernous armpits are quite sufficient to act as a pesticide agent for all the cocaine fields in the entire country of Columbia or a pretext for another mandatory masking.

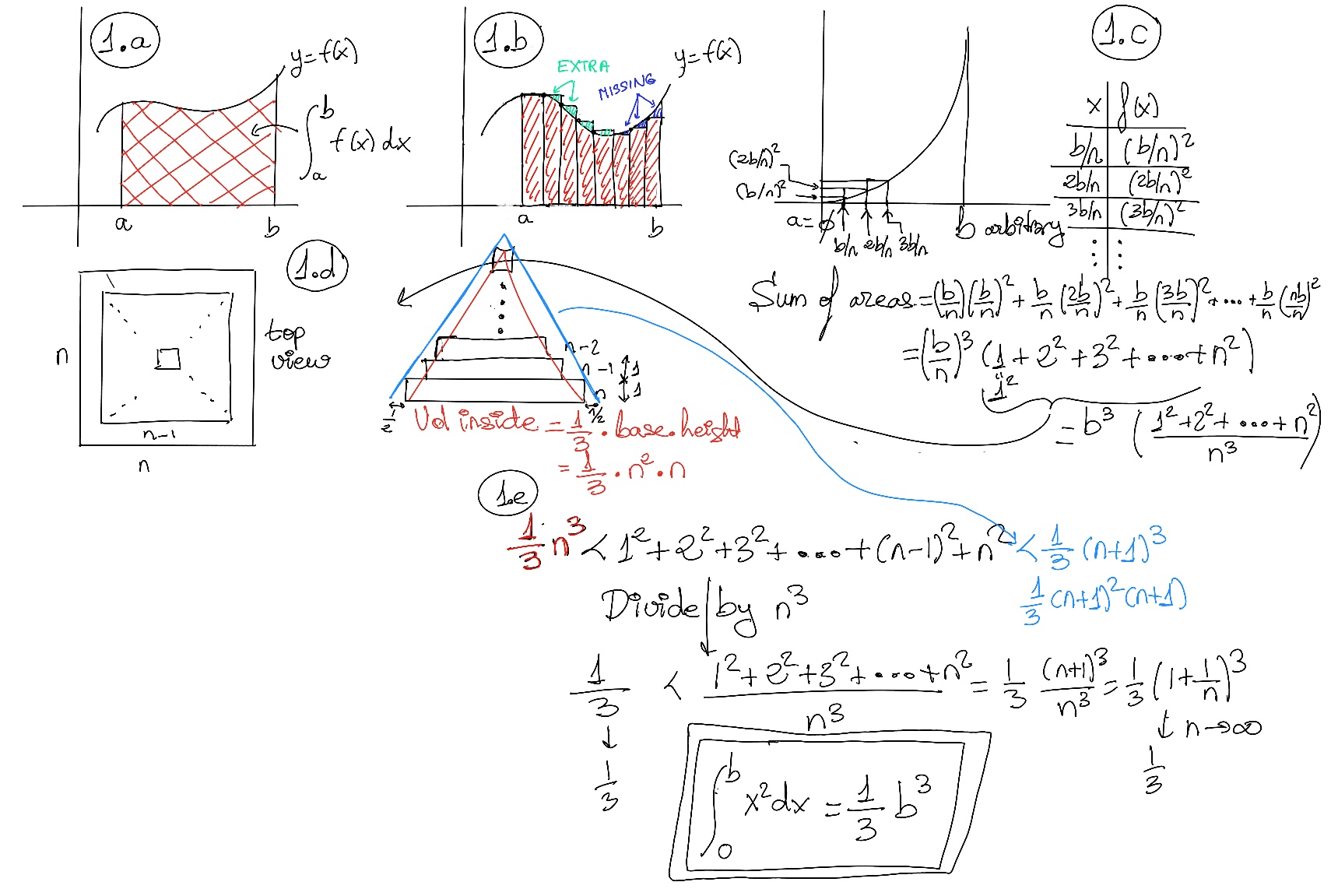

A definite integral is a mathematical concept used to find the area under a curve between two fixed limits. It is represented as $\int_{a}^{b}f(x)dx$, where a and b are the lower and upper limits, and f(x) is the integrand.

A definite integral of a function is defined as the area of the region bounded by the function's graph or curve between two points, say a and b, and the x-axis. The integral of a real-valued function f(x) on an interval [a, b] is written or expressed as $\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx$ and it is illustrated in Figure 1.a.

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus states roughly that the integral of a function f over an interval is equal to the change of any antiderivate F (F'(x) = f(x)) between the ends of the interval, i.e., $\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx = F(b)-F(a)=F(x) \bigg|_{a}^{b}$

Definite integrals have specific limits of integration that determine the net area under the curve of the function between these limits. Improper integrals arise when the interval of integration is unbounded, that is, $\int_{a}^{∞} f(x)dx = \lim_{b \to ∞}\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx$, or when the integrand is undefined at certain points within the interval of integration. Techniques for evaluating improper integrals involve taking limits as the integration bounds approach infinity or as singularities are approached.

Theorem (p-series) Coordinates Calculus.

Limit or asymptotic comparison. Assume f, g are positive continuous functions. If f(x) ≈ g(x) as x → ∞, that is, $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = c$, c ≠ 0 then $\int_{a}^{∞} f(x)dx$ and $\int_{a}^{∞} g(x)dx$ both improper integrals converge or both diverge.

Proof.

$\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = c$ ⇒ ∃a: |f(x)⁄g(x)-c| < c/2 ∀x>a ⇒ -c/2 < f(x)⁄g(x)-c < c/2 ⇒ -cg(x)/2 < f(x)-cg(x) < cg(x)/2 ⇒[Adding +cg(x)] c⁄2g(x) < f(x) < 3cg(x)/2 ∀x>a ⇒ $\frac{c}{2}\int_{a}^{∞} g(x)dx < \int_{a}^{∞} f(x)dx < \frac{3c}{2}\int_{a}^{∞} g(x)dx$. These inequalities show that both integrals converge or both diverge simultaneously, QED.

Comparison Theorem. Suppose that f and g are continuous functions with f(x) ≥ g(x) ≥ 0 ∀x ≥ a.

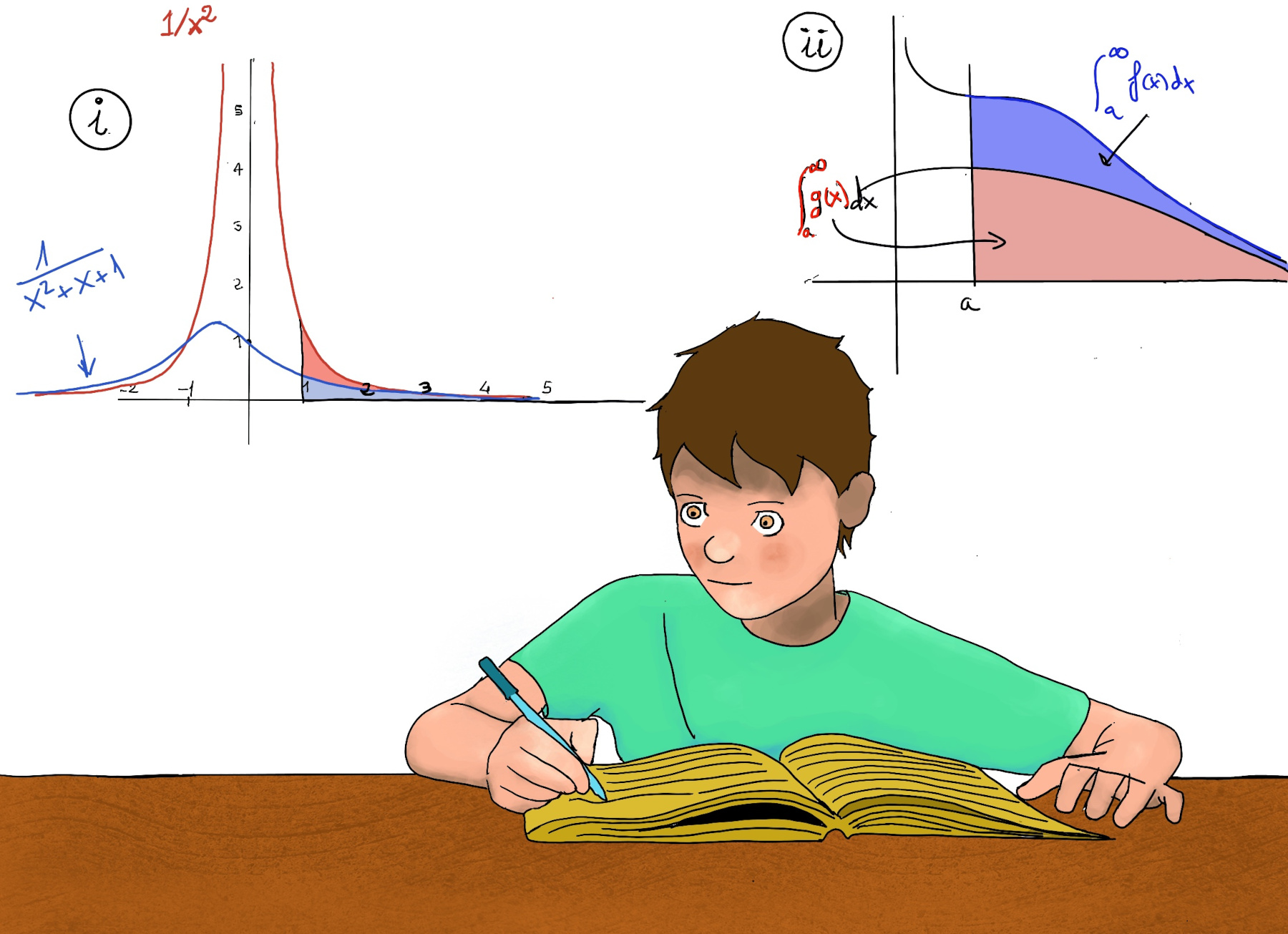

∀x ≥ 1 ⇒ x + 1 ≥ 1 > 0 ⇒ x2 + x + 1 > x2 ⇒[Taking reciprocals] $\frac{1}{x^2+x+1} < \frac{1}{x^2}$ ⇒ ∀b > 1, $\int_{1}^{b} \frac{1}{x^2+x+1}< \int_{1}^{b} \frac{1}{x^2}$ ⇒[Taking the limits (Properties of Limits)] $\lim_{b \to ∞} \int_{1}^{b} \frac{1}{x^2+x+1} < \lim_{b \to ∞} \int_{1}^{b} \frac{1}{x^2} ↭ \int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^2+x+1}< \int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^2}$, and since we know (Theorem (p-series), p = 2 > 1), $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^2}$ converges, then we can conclude that our original integral $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^2+x+1}$ also converges.

The comparison of these improper integrals can be visualized by comparing the area under each function (Figure i). The idea is quite simple, if the area under the larger function is finite (i.e. the improper integral $\int_{a}^{∞} f(x)dx$ converges), the area under the smaller function must also be finite (i.e., $\int_{a}^{∞} g(x)dx$ converges) -Figure ii-. Likewise, if the area under the smaller function is infinite (i.e., $\int_{a}^{∞} g(x)dx$ diverges), then the area under the larger function must also be infinite (i.e. the improper integral $\int_{a}^{∞} f(x)dx$ diverges).

$\int_{0}^{∞} \frac{dx}{\sqrt{x^2+10}} = \int_{0}^{1} \frac{dx}{\sqrt{x^2+10}} + \int_{1}^{∞} \frac{dx}{\sqrt{x^2+10}}$. Consider that $\sqrt{x^2+10}≈\sqrt{x^2}=x$ as x → ∞ ⇒ $\frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2+10}} ≈ \frac{1}{x}, \int_{0}^{1} \frac{dx}{\sqrt{x^2+10}}$ is a certain (finite) number, and $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{dx}{x}$ diverges, so our original improper integral diverges.

$\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{x^2-1}{2x^5+3x+12}dx$ converges because $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{x^2-1}{2x^5+3x+12}dx ≤ \int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{2x^3}dx$ [🚀] and we know that $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{2x^3}dx = \frac{1}{2}\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^3}dx$ and by Theorem (p-series) the last integral converges, p = 3 > 1.

[🚀] ∀x ≥ 1, $0 ≤ \frac{x^2-1}{2x^5+3x+12} ≤ \frac{1}{2x^3} ↭$[x ≥ 1 ⇒ x2-1≥ 0, 2x5+3x+12 ≥ 0] $2x^3(x^2-1) ≤ 2x^5+3x+12 ↭ 2x^5-2x^3 ≤ 2x^5+3x+12 ↭ -2x^3 ≤ 3x+12$ and that is always true because -2x3 < 0 ≤ 3x+12 ∀x ≥ 1.

∀x≥2, $\frac{x^2+x+1}{x^3-\sqrt[3]{x}} ≥ \frac{x^2}{x^3-\sqrt[3]{x}} ≥ \frac{x^2}{x^3} = \frac{1}{x}.$ $\int_{2}^{∞} \frac{1}{x}dx$ diverges by Theorem (p-series), p = 1, hence $\int_{2}^{∞} \frac{x^2+x+1}{x^3-\sqrt[3]{x}}dx$ diverges by the comparison test for improper integrals.

$\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{sin^2(x)}{x^2}dx$. $\frac{sin^2(x)}{x^2}dx ≤ \frac{1}{x^2}$ on [1, ∞), $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^2}dx$ is convergent (Theorem, p-series, p = 2 ≥ 1) ⇒ $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{sin^2(x)}{x^2}dx$ converges by comparison.

$\int_{0}^{∞} \frac{dx}{\sqrt{x^3+7}}$ [$\frac{1}{\sqrt{x^3+7}}≈\frac{1}{\sqrt{x^3}}=\frac{1}{x^{3/2}}$] ≈ $\int_{0}^{∞} \frac{dx}{x^{3/2}}$ converges (Theorem, p-series, p = 3⁄2 ≥ 1)⇒ By the comparison test for improper integrals, it follows that our original integral converges.

$\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{x-2}{x^3+1}$

$\frac{x-2}{x^3+1}< \frac{x}{x^3+1}$ on [1, ∞). Futhermore, $\frac{x}{x^3+1} < \frac{x}{x^3} = \frac{1}{x^2} ⇒ \frac{x-2}{x^3+1} < \frac{1}{x^2}$. $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^2}$ converges (Theorem, p-series, p = 2 ≥ 1) ⇒[By the comparison test for improper integrals] $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{x-2}{x^3+1}$ converges.

We know that $\frac{cos(x)}{\sqrt{x}} ≤ \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}$ on [0, π⁄2].

$\int_{0}^{\frac{π}{2}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}dx = \lim_{a \to 0} \int_{a}^{\frac{π}{2}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}dx = \lim_{a \to 0} \int_{a}^{\frac{π}{2}} 2\sqrt{x}\bigg|_{a}^{\frac{π}{2}} =$

$\lim_{a \to 0} 2\sqrt{\frac{π}{2}}-2\sqrt{a} = 2\sqrt{\frac{π}{2}} = \sqrt{2π}$ ⇒ $\int_{0}^{\frac{π}{2}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}dx$ converges ⇒[By the comparison test for improper integrals] $\int_{0}^{\frac{π}{2}} \frac{cos(x)}{\sqrt{x}}dx$ converges

We know that $2\int_{0}^{1} e^{-x^2}dx$ is a finite number and regarding the integral $+2\int_{1}^{∞} e^{-x^2}dx$, $e^{x^2}≥x^2$ on [1, ∞) because nothing grows faster than the exponential ⇒ $e^{-x^2} = \frac{1}{e^{x^2}} ≤ \frac{1}{x^2}$. Futhermore, $\int_{0}^{1} \frac{1}{x^2}dx$ is convergent ⇒ $\int_{1}^{∞} e^{-x^2}dx$ is convergent ⇒ $\int_{-∞}^{∞} e^{-x^2}dx$ is convergent.

The Gaussian integral, also known as the Euler–Poisson integral, is the integral of the Gaussian function $f(x)=e^{-x^{2}}$ over the entire real line. $\int_{-∞}^{∞} e^{-x^2}dx = \sqrt{π}$

$\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1+\frac{1}{e^x}}{x}dx$. As x approaches infinity, the integrand $\frac{1+\frac{1}{e^x}}{x}dx$ behave like $\frac{1}{x}, \frac{1+\frac{1}{e^x}}{x} ≈ \frac{1}{x}$. The integral $\int_{1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{x}dx$ is a well-known improper integral and diverges ⇒ $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1+\frac{1}{e^x}}{x}dx$ diverges.

$\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{x-1}{x^4+2x^2}dx$

$∀x≥1, \frac{x-1}{x^4+2x^2}≤\frac{x}{x^4+2x^2}=\frac{x}{x(x^3+2x)}=\frac{1}{x^3+2x}≤\frac{1}{x^3}$. Therefore, $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{x-1}{x^4+2x^2}dx ≤ \int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^3}dx$, and our original converges because $\int_{1}^{∞} \frac{1}{x^3}dx$ converges (Theorem (p-series), p = 3 > 1).