|

|

|

|

|

|

The Compound Effect is the principle of reaping huge rewards from a series of small, smart choices, Darren Hardy.

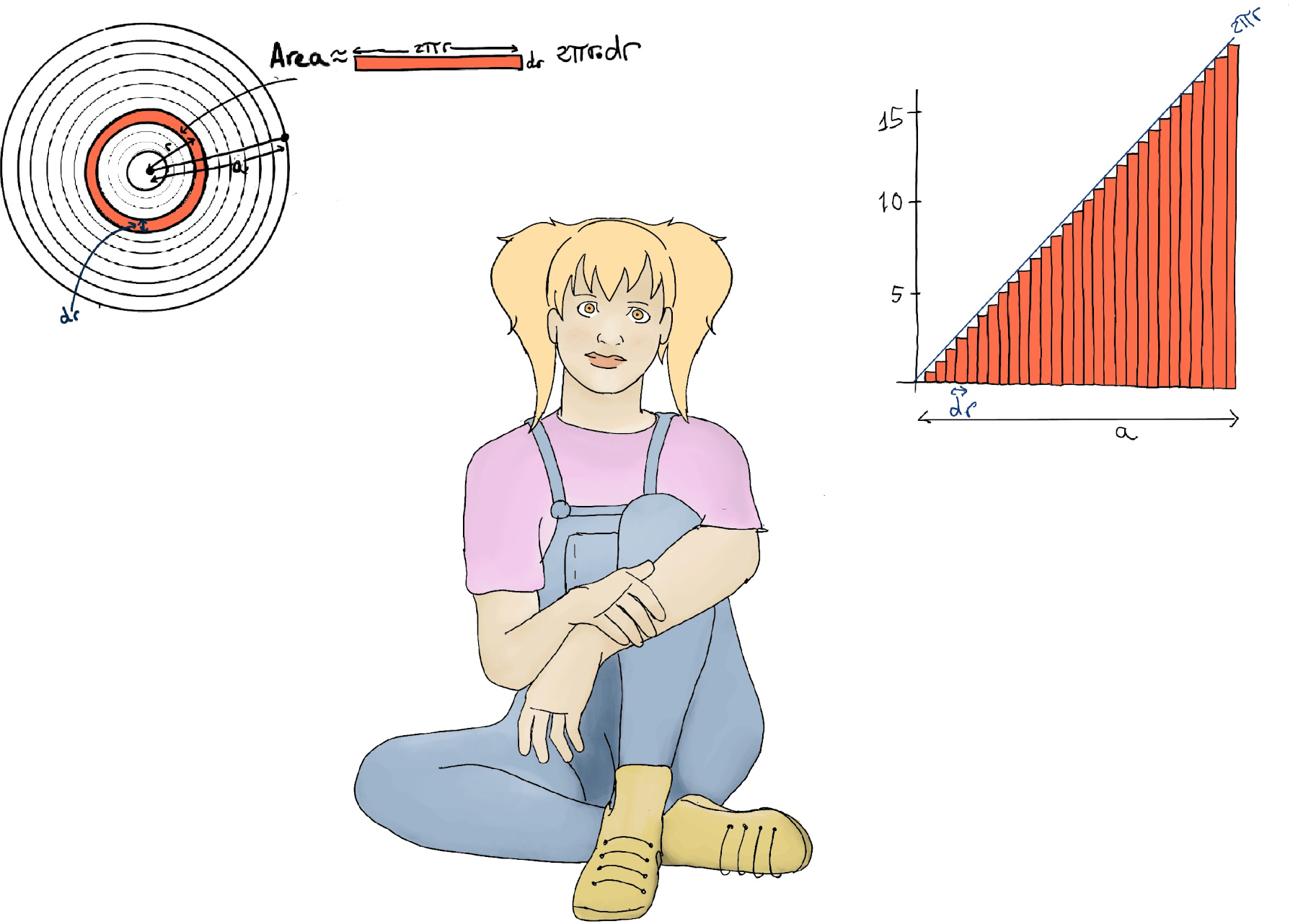

How to calculate the area of a circle of radius a? The best approximation is slicing the circle into many concentric rings. We can approximate the area of any of these concentric rings by 2πr·dr. So we can approximate the area of the whole circle by the sum of these areas (their values of r ranges from “0” to “a” spaced out by dr). This approximation gets more accurate as the size of dr gets smaller and smaller.

We can plot these areas and have a triangle with a base of “a” and a height that is 2π·a, so its area is $\frac{1}{2}·base·height = \frac{1}{2}·a·(2π·a) = π·a^2$

Futhermore, the sum of these rectangles approximates the area under the graph 2πr. More formally, $\int_{0}^{a} 2πrdr = 2π\int_{0}^{a} rdr = 2π\frac{r^2}{2} \bigg|_{0}^{a} = 2π\frac{a^2}{2}-2π\frac{0^2}{2}= π·a^2.$

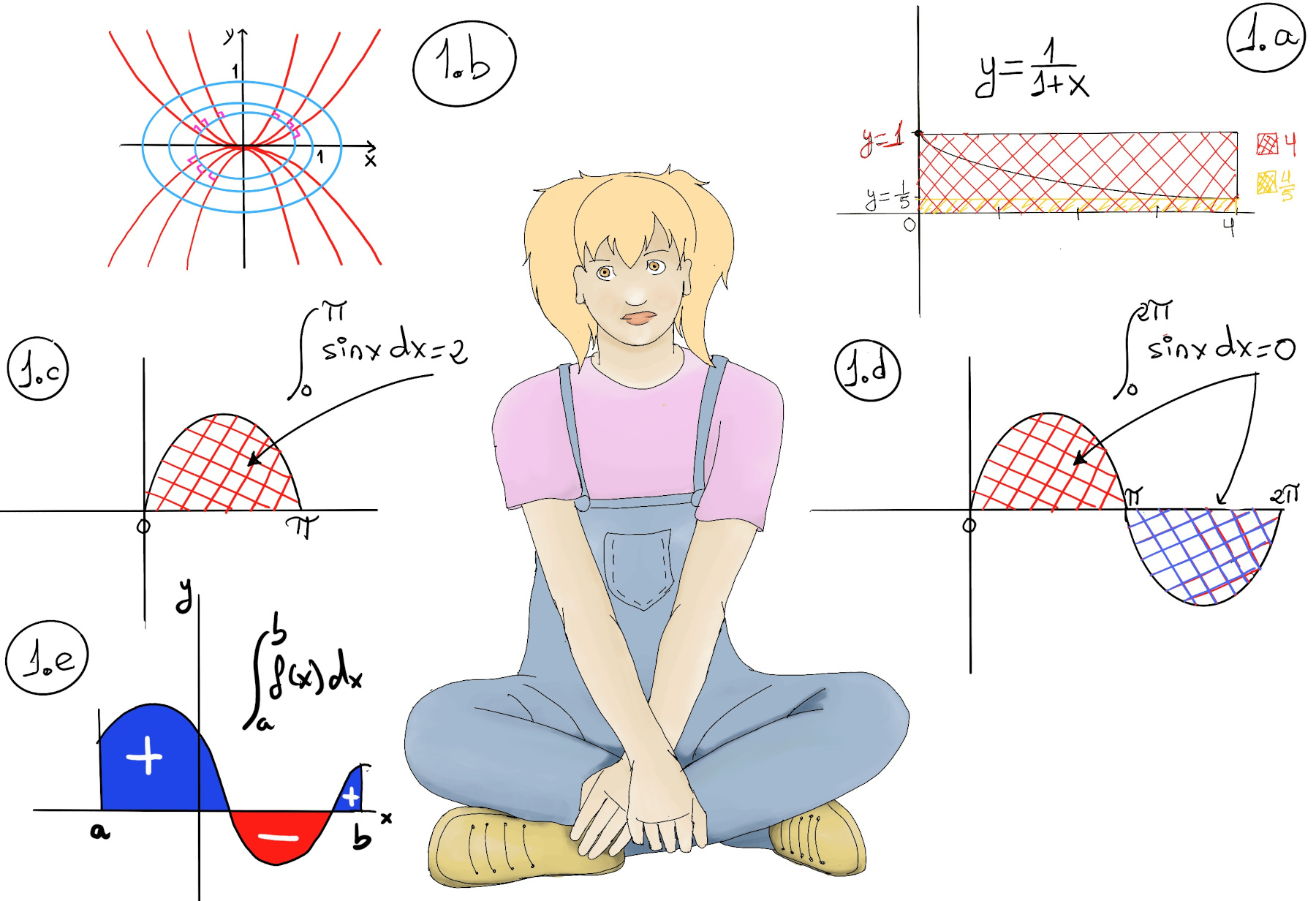

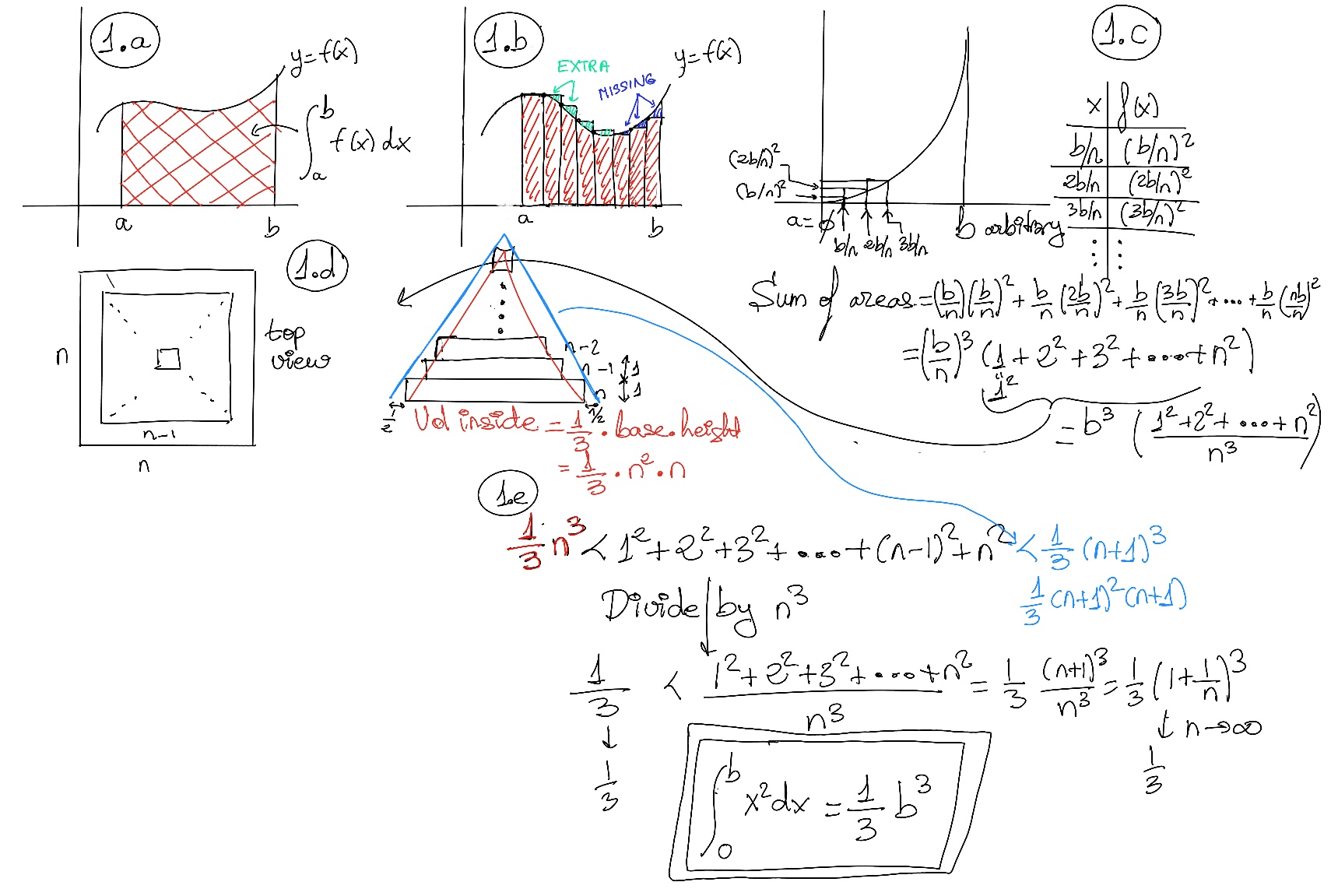

A definite integral is a mathematical concept used to find the area under a curve between two fixed limits. It is represented as $\int_{a}^{b}f(x)dx$, where a and b are the lower and upper limits, and f(x) is the integrand.

A definite integral of a function is defined as the area of the region bounded by the function's graph or curve between two points, say a and b, and the x-axis. The integral of a real-valued function f(x) on an interval [a, b] is written or expressed as $\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx$ and it is illustrated in Figure 1.a.

To compute the area, we can divide the region under the function into a series of rectangles whose areas corresponds to function values as heights that are multiplied by the step width to calculate the total sum. Of course, we need to rectify this sum (it is just an approximation) by taking a limit, and as the rectangles get infinitesimally thin, we achieve the desired result (Figure 1.b.).

Let’s try to calculate $\int_{0}^{b} x^2dx$ where a = 0 and b is arbitrary. We divide the segment [0, b] into n pieces (Figure 1.c.). The sum of the areas of all rectangles is equal to $(\frac{b}{n})·(\frac{b}{n})^2+(\frac{b}{n})·(\frac{2b}{n})^2+(\frac{b}{n})·(\frac{3b}{n})^2+···+(\frac{b}{n})·(\frac{nb}{n})^2 = b^3(\frac{1^2+2^2+3^2+···n^2}{n^3})$

To try to understand ${1^2+2^2+3^2+···n^2}$, we can observe that it is basically a pyramid, the base of which is n x n blocks. On top of it, we put a second layer of n-1 x n-1 blocks (Figure 1.d). And we keep on piling up layer after layer. At the top of the pyramid, there is just one block of stone. Underneath our staircase pyramid, there is an ordinary pyramid, and its volume is $\frac{1}{3}(baselength~ ·~ baseheight)·height=\frac{1}{3}n^2~ ·~ n$ On the outside, there is also another ordinary pyramid, with base_length, base_height, and height (n+1), (n+1), and (n+1) respectively.

So our initial quantity ${1^2+2^2+3^2+···n^2}$ is to be found or bounded between these two pyramids: $\frac{1}{3}n^3 < 1^2+2^2+3^2+···n^2 < \frac{1}{3}(n+1)^3$ (Figure 1.e.) If we divide by n3, $\frac{1}{3} < \frac{1^2+2^2+3^2+···n^2}{n^3} < \frac{1}{3}(1+\frac{1}{n})^3$. When n→ infinite, the left and right side tends to $\frac{1}{3}$, and by the Squeeze Infinite, $\frac{1^2+2^2+3^2+···n^2}{n^3} → \frac{1}{3}$ Therefore, our total area $\int_{0}^{b} x^2dx=\frac{1}{3}b^3.$

A Riemann sum is another approximation of an integral by a finite sum. The interval is partitioned into n pieces and we pick any height of f in each interval (e.g. f(ci)) The sum is defined as $\sum_{i=1}^n f(c_i)\Delta x,~ where~\Delta x=\frac{b-a}{n}$ Please notice that in the limit, as the rectangles get thinner and thinner, the difference between the area covered by the rectangles and the area under the curve will get smaller and smaller, and finally it does not matter our choices (ci), we get the desired result, that is, $\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx$.

How much money do we borrow in the whole year? $\sum_{i=1}^{365} f(\frac{i}{365})\Delta t$ → [It is going to be very close] $\int_{0}^{1} f(t)dt$

How much money do you actually owe? Obviously, and regretfully, the interest on our debt is compounded continuously. If P is our principal (we start with a debt of P), then after some time t you owe Pert where r is the interest rate.

Compound interest is an interest calculated on both the principal and the existing interest over a given period of time. Its formula is $P(1 +\frac{r}{n})^{nt}$ where n is the number of terms the initial amount or principal P is compounding in the time t. If our debt is compounded continuously, then after time we owe $\lim_{n \to ∞} P(1 + \frac{r}{n})^{nt}=Pe^{rt}$ and we are using the fact that $\lim_{n \to ∞} (1 + \frac{r}{n})^{n} = e^r$.

So, you borrow these amounts $f(\frac{i}{365})\Delta t$, but when you borrow these quantities, the amount of time left in the year is 1 -i/365, which is the amount of time this incremental debt will accumulate interest, that is, $(f(\frac{i}{365})\Delta t)e^{r(1-\frac{i}{365})}$. An at the end of the year, $\sum_{i=1}^{365} (f(\frac{i}{365})\Delta t)e^{r(1-\frac{i}{365})}$ that is basically $\int_{0}^{1} e^{r(1-t)}f(t)dt$.

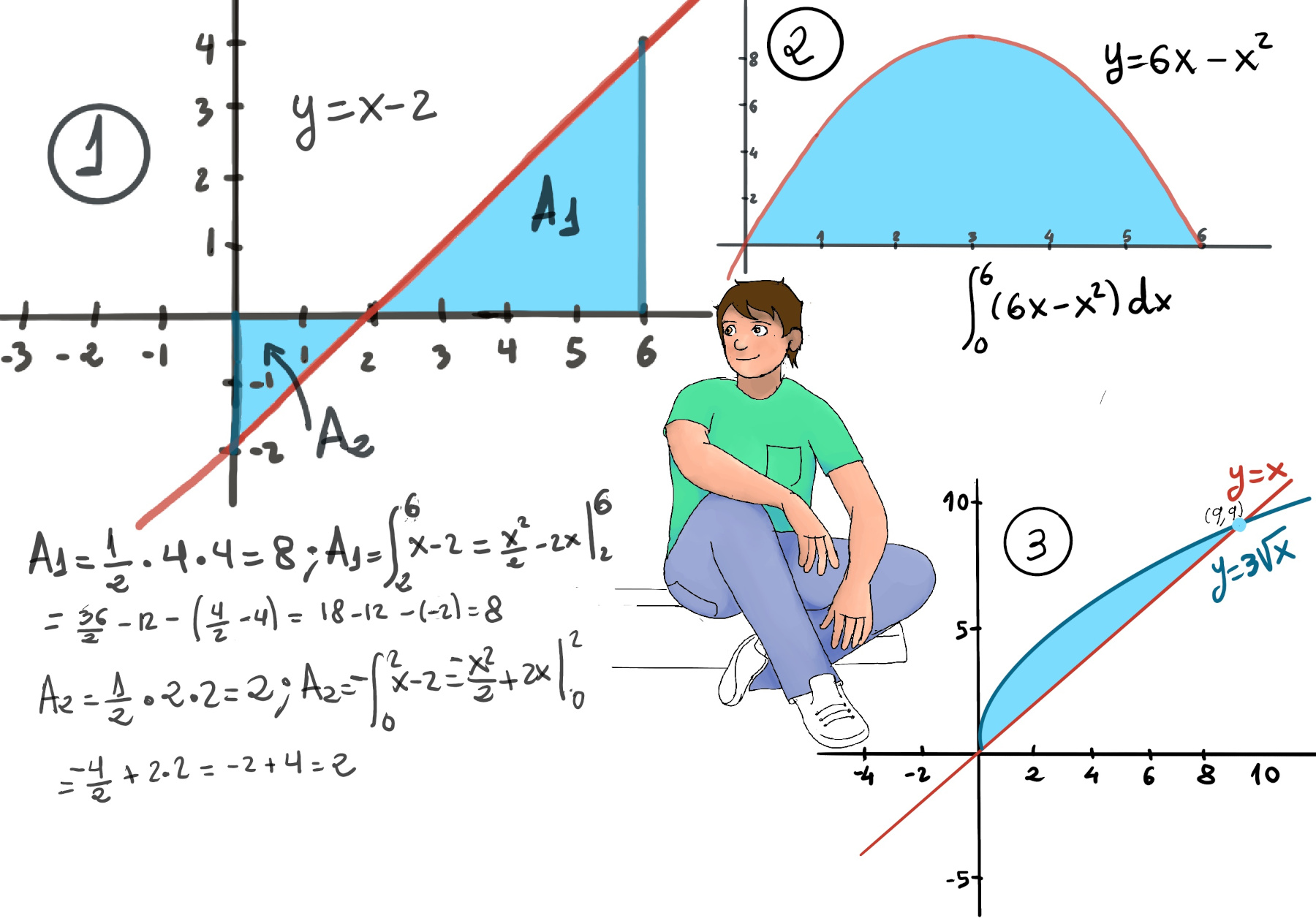

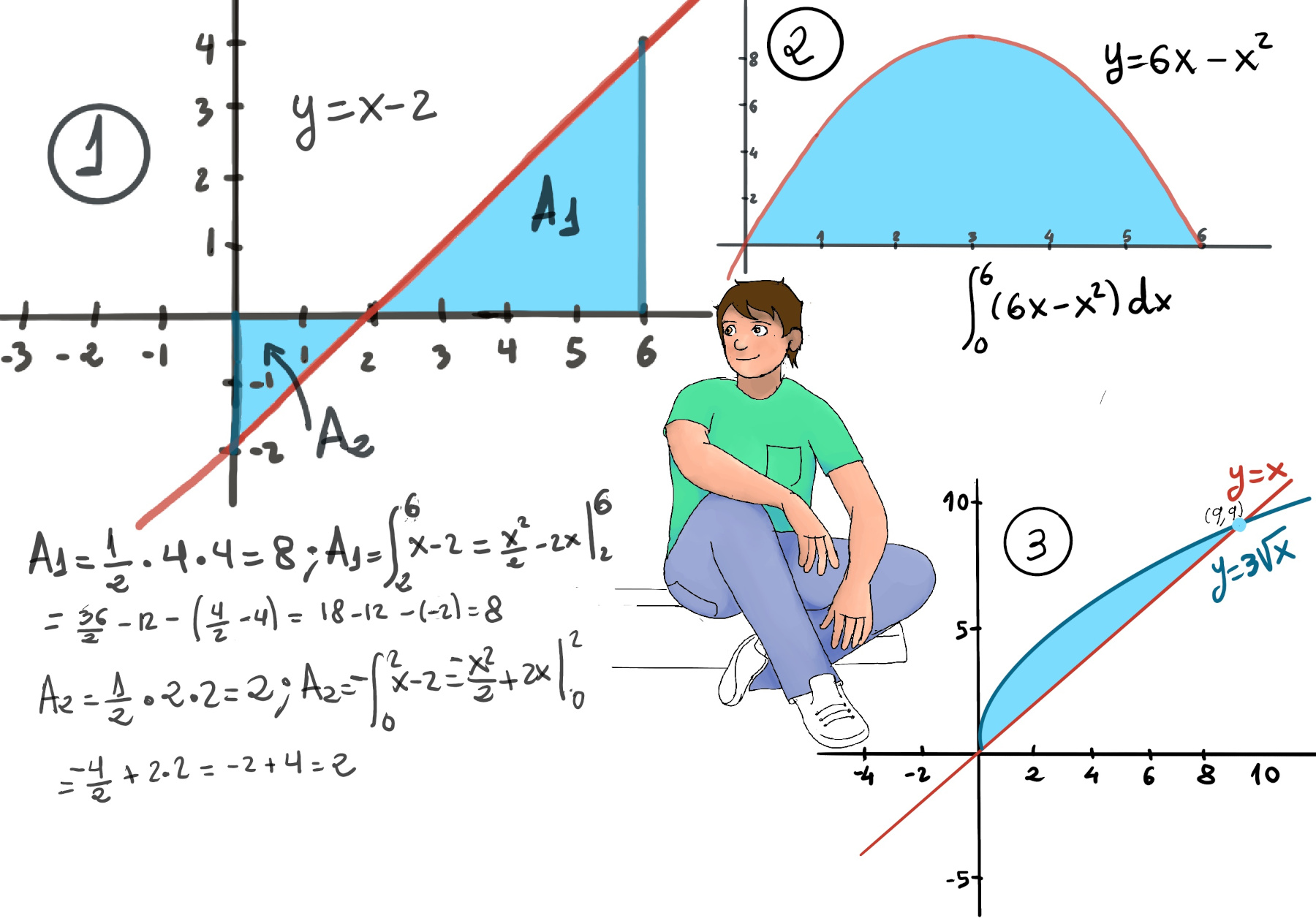

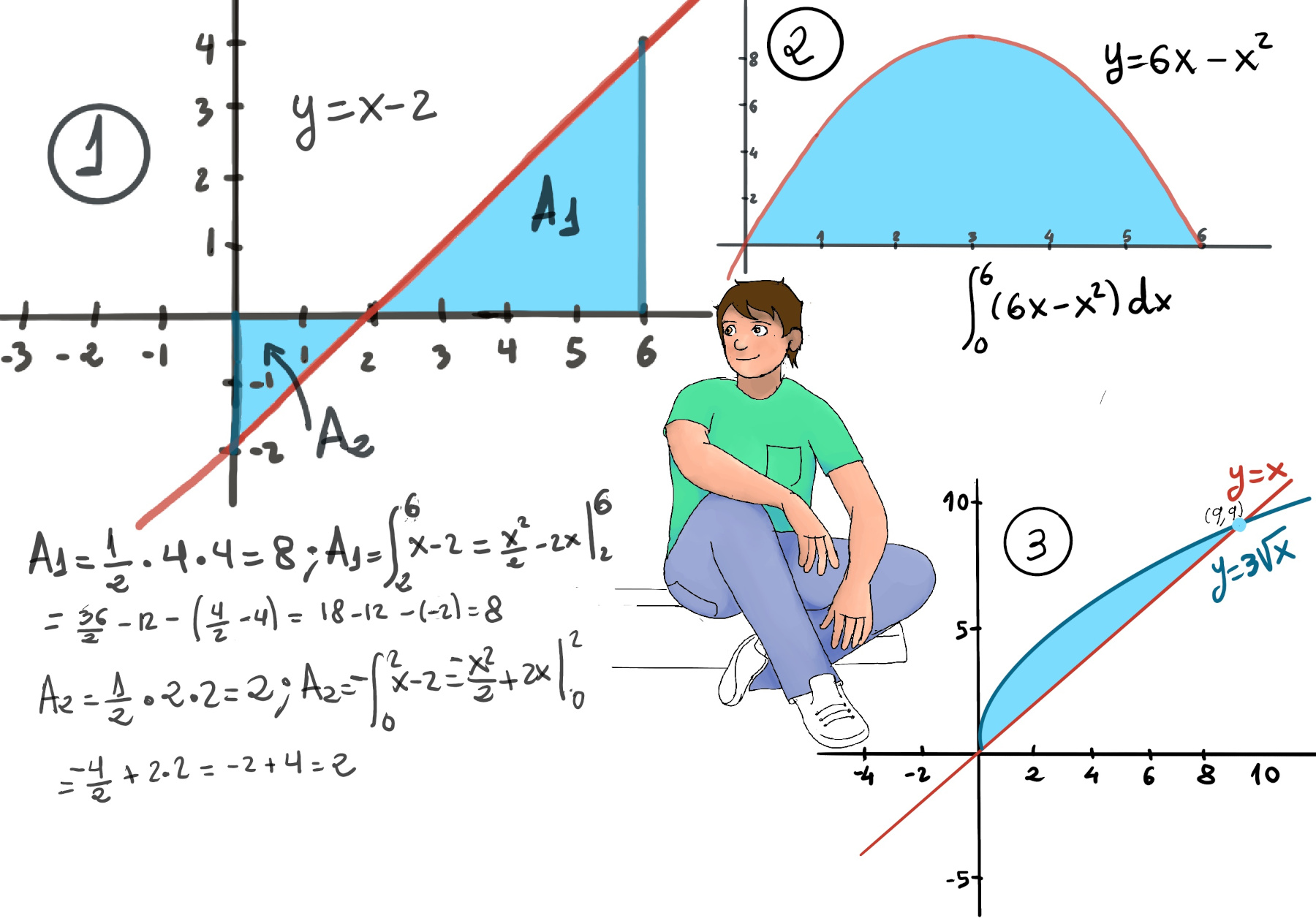

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus states roughly that the integral of a function f over an interval is equal to the change of any antiderivate F (F'(x) = f(x)) between the ends of the interval, i.e., $\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx = F(b)-F(a)=F(x) \bigg|_{a}^{b}$

Examples:

For some distance s(t), the velocity function is v(t)=s’(t). Therefore, given a velocity function, v(t) (v(t) is what is measured in the speedometer), $\int_{a}^{b} v(t)dt$ =s(b)-s(a) where s(b) - s(a) is the actual distance traveled, that is, what is measured in the odometer, that is, the instrument on your car dashboard that displays how many miles or kilometers your vehicle has traveled.

Let’s say that you checked your speedometer every single second (Is your phone out of juice? 😃. Seriously, $\Delta t = 1~ second$), $v(t_i)\Delta t$ is the distance traveled in the ith second, the Riemman Sum is equal $\sum_{i=1}^n v(t_i)\Delta t≈\int_{a}^{b} v(t)dt$ = s(b)-s(a) -how far you have traveled-.

Let’s notice that $\int_{0}^{2π} sinxdx = (-cosx)\bigg|_{0}^{2π}=-cos2π-(-cos0) = -1 -(-1) = 0$ (Figure 1.d.)

💡A definite integral of a function should be interpreted as the signed area of the region in the plane that is bounded by its graph and the horizontal axis. Be extremely careful, areas above the horizontal -x- axis of the plane are positive while areas below the horizontal axis are considered negative (Figure 1.e.).