|

|

|

Get your facts first, then you can distort them as you please, Mark Twain.

“How are you doing pal?” “Sucking air, pumping blood, and slowly maintaining an undignified, insignificant existence while pretending but fooling nobody, to overcome a life of suppressed rage, unknown biases, dark areas, emotional rollercoaster, and most importantly, blatant denial,” Apocalypse, Anawim, #justtothepoint.

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

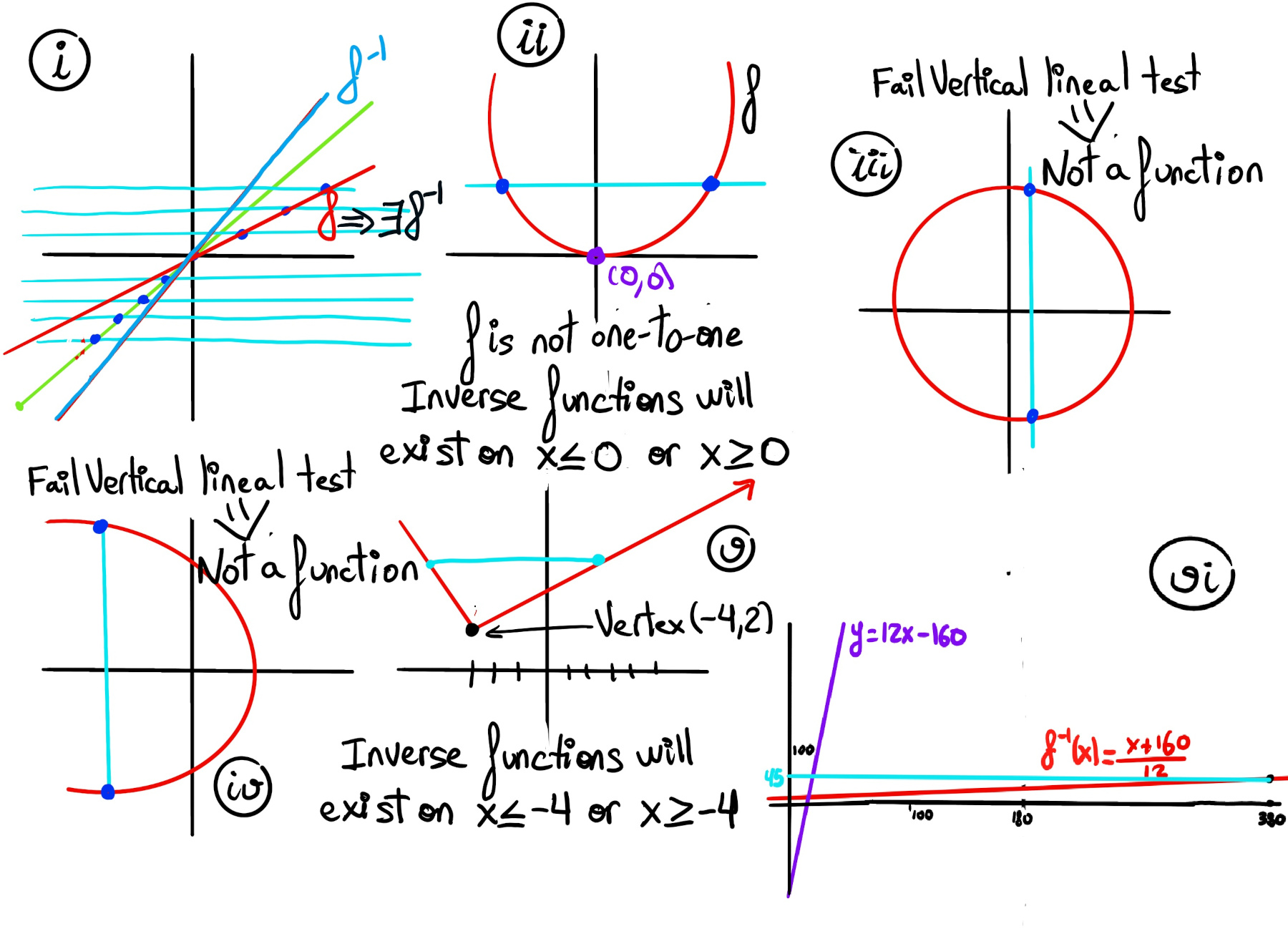

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ. A mathematical function can be thought of as a black box (or machine) that takes an input from its domain and produces exactly one output in its codomain. Inside the machine lives a specific rule (formula, procedure, or mapping) that dictates or tells you which output corresponds to each input, and a key property is uniqueness —each input maps to a single, deterministic output. No input can ever produce two different results (Figure E). The function f(x) = x2 accepts any real number x (domain: ℝ) and returns exactly one non-negative value x2 (output in codomain: [0,∞)). The input 3 always yields 9, never any other value.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$.💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

First Derivative Test. Let f be differentiable on an open interval containing c, except possibly at c itself, and let c be a critical point (so f′(c) = 0 or f′ is undefined). Then:

Loosely speaking, the inverse function of a function f is a function that undoes the operation of the original function. If a function f maps each element x in its domain to a unique element y in its codomain, then the inverse function, denoted by $f^{-1}$, maps each such element y back to its corresponding x.

Formally, if f(x) = y, then $f^{-1}(y) = x$. This relationship can be summarized by the identities $f^{-1}(f(x)) = x, \forall x \in \mathrm{Dom}(f),$ and $f(f^{-1}(y)) = y, \forall y \in \mathrm{Dom}(f^{-1}).$

For a given function f, its inverse g = f-1 is a function that reverses the input and output of the original function.

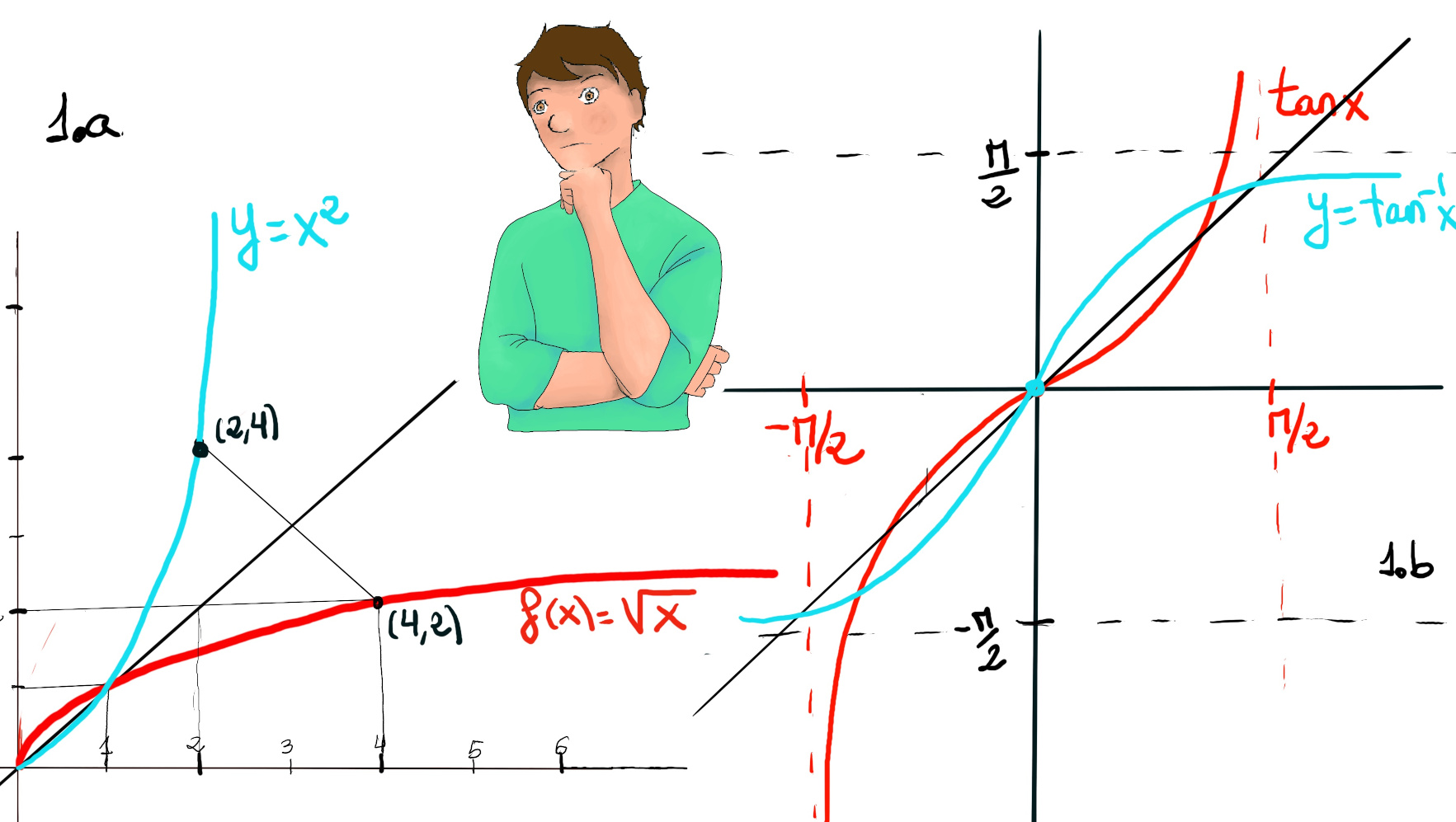

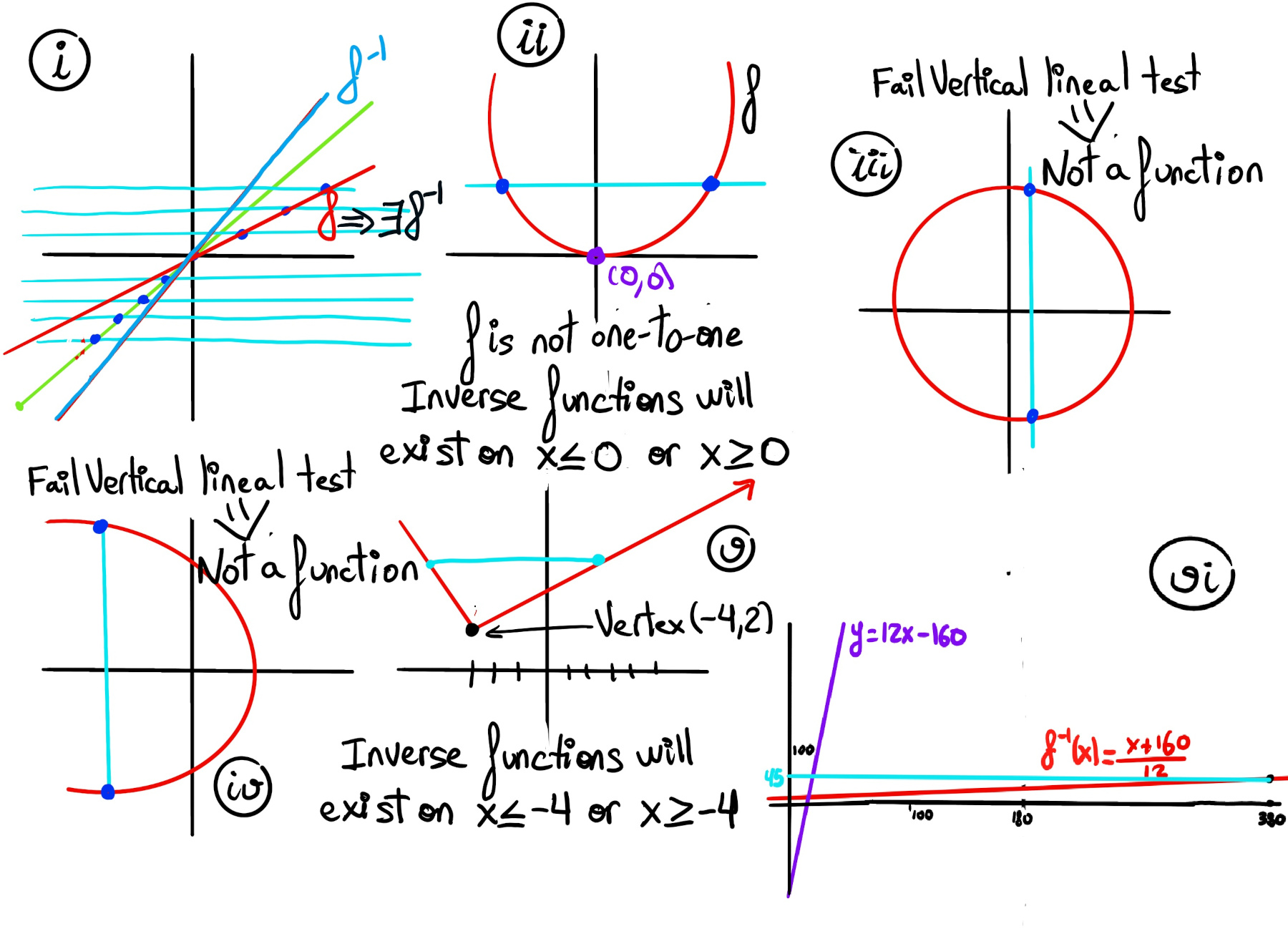

If you want to plot or graph the inverse of a function, simply reflect the graph of f(x) across the line y = x. A point (a, b) on the graph of f corresponds to the point (b, a) on the graph of $f^{-1}$ and the line y = x acts as a mirror.

For an inverse function to exist, the original function must be both one-to-one (injective) and onto (surjective).

Definition. A function $f: A \to B$ is one-to-one (injective) if distinct inputs produce or map to distinct outputs. In other words, each element in the domain maps to a distinct (unique) element in the codomain. Formally, $\forall x_1, x_2 \in A, f(x_1)=f(x_2) \Rightarrow x_1=x_2$. Graphically, this means the function passes the horizontal line test (every horizontal line intersects the graph at most once).

Definition. A function $f: A \to B$ is onto (surjective) if every element in the codomain is the image of at least one element in the domain A or has a pre-image in the domain. In other words, the range of f is equal to the entire codomain B. Formally, $\forall b\in B, \exist a\in A: f(a) = b$.

A function that is both injective and surjective is called a bijection. This establishes a perfect “pairing” between every element of A and every element of B.

$ x = \frac{2y+5}{3y-2} ⇒ 3yx -2x = 2y + 5 ⇒ y(3x-2) = 2x + 5 ⇒ f^{-1}(x) = \frac{2x+5}{3x-2}.$ Notice that this function is its own inverse.

Polynomial. Let f(x) = x3 -1. The inverse function is found by switching the roles of x and y and solving for y: x = y3 -1 ↭ y3 = x +1 ↭ $f^{-1}(x) = \sqrt[3]{x+1}$. This function is invertible on all of $\mathbb{R}$ because it is strictly increasing.

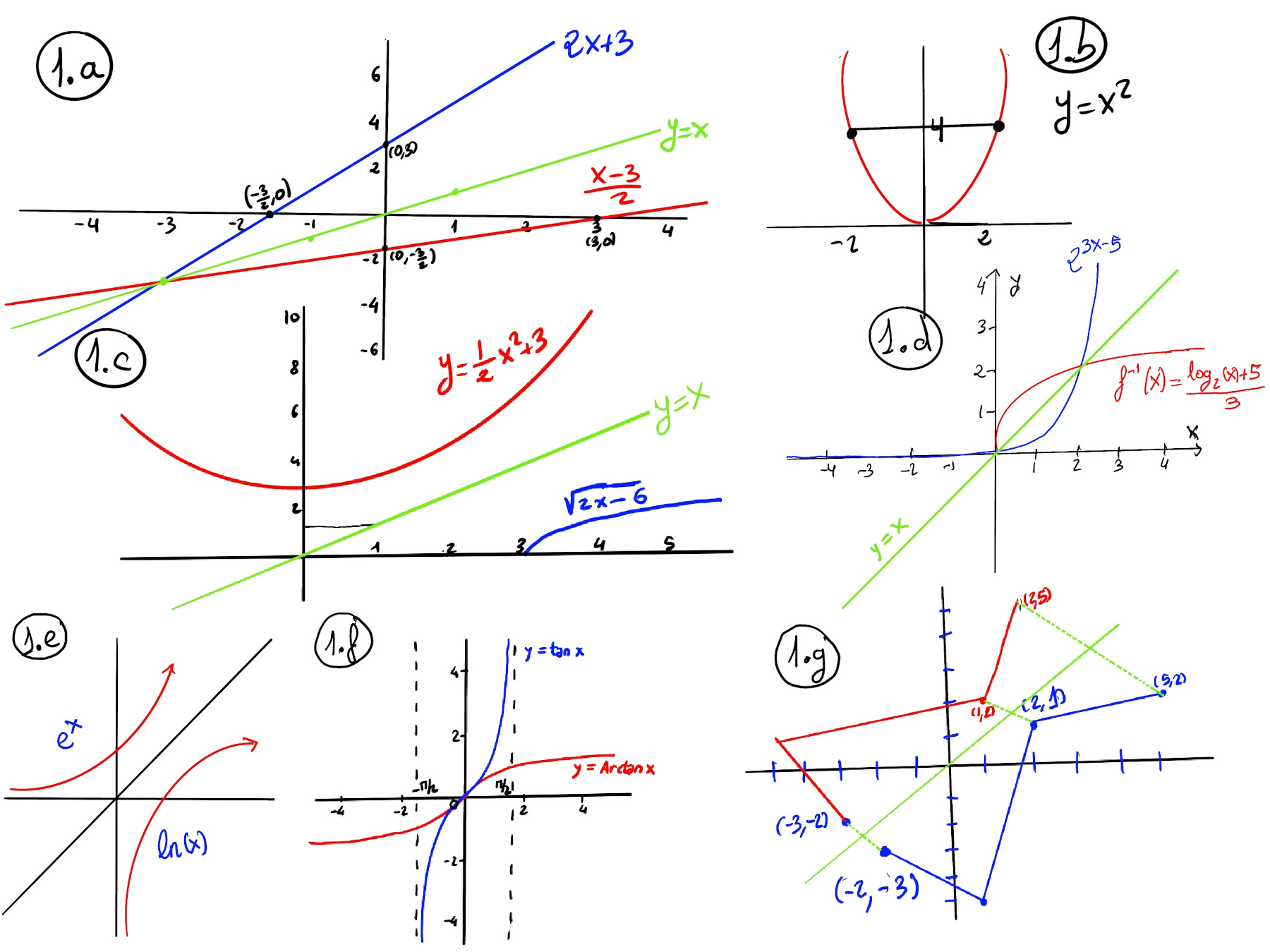

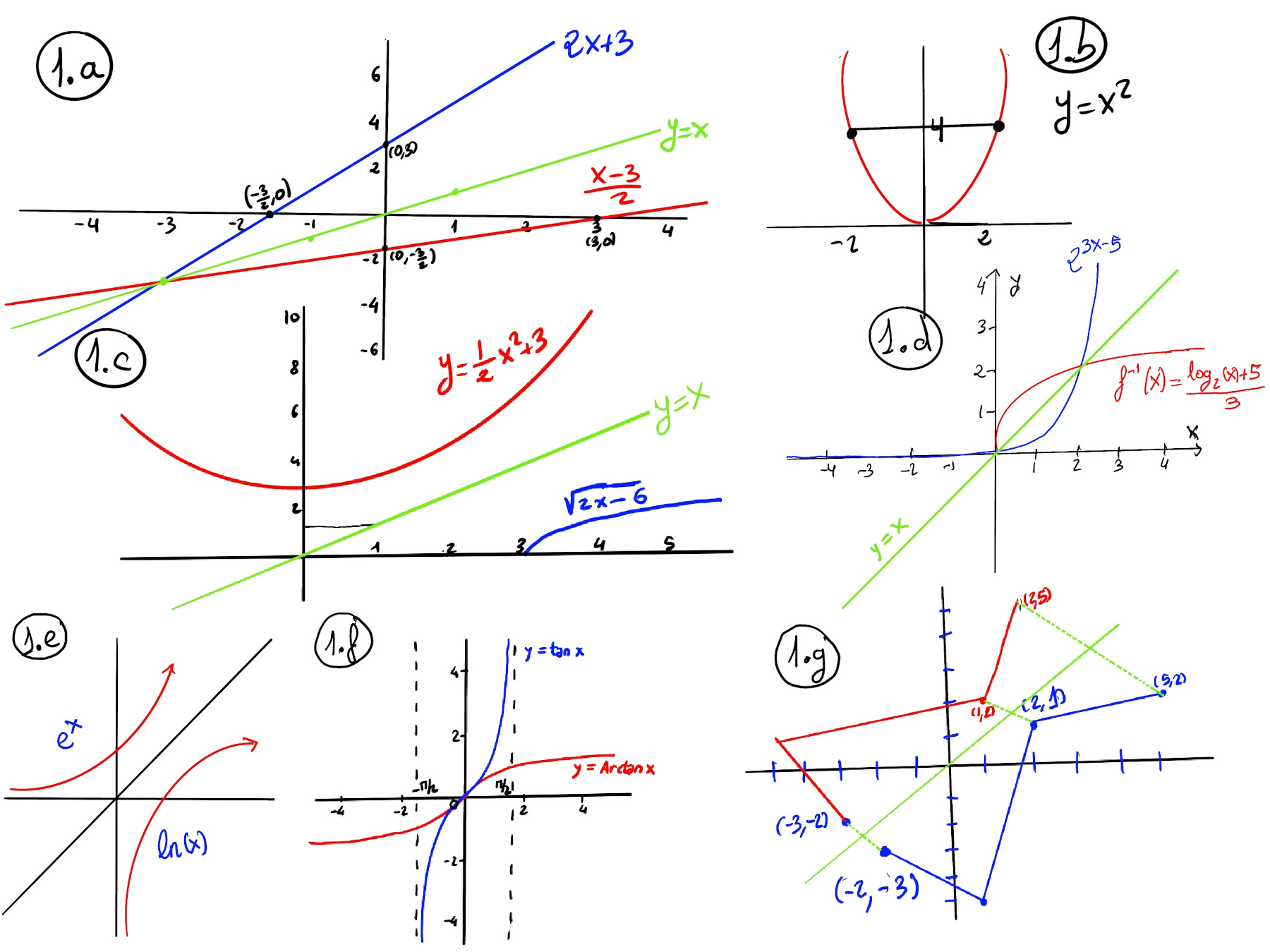

Linear function. Let f(x) = 2x + 3. This function is one-to-one and onto. The inverse function is found by switching the roles of x and y and solving for x: y = 2x + 3 ↭ $x = \frac{y - 3}{2}$. Thus, $f^{-1}(x) = \frac{x - 3}{2}$ (Figure 1.a).

Counterexample, A function without an inverse on $\mathbb{R}$. Let f(x) = x2. This function is not one-to-one since f(2) = f(-2) = 4, hence it does not have an inverse over ℝ. However, if we restrict the domain to $x \ge 0$, the inverse exists and is $f^{-1}(x) = \sqrt{x}$ (Figure 1.b.).

Radical function with restricted domain. Let f(x) = $\sqrt{2x -6}$. Notice that Domain(f) = [3, ∞] because $2x - 6 \ge 0 \implies x \ge 3$, Range(f) = [0, ∞) (Figure 1.c).

y = $\sqrt{2x -6}$. To find the inverse of a function, you need to switch the roles of x and y, and then solve for y in terms of x. $x = \sqrt{2x -6} ⇒ x^2 = (\sqrt{2y-6})^2 ⇒ x^2 = 2y -6 ⇒ f^{-1}(x) = \frac{1}{2}x^2 + 3.$ with domain [0, ∞) and range [3, ∞). Notice that the domain of $f^{-1}$ is the range of f.

Always check whether a function is one-to-one before attempting to find its inverse. Furthermore, many functions become invertible after an appropriate domain restriction.

Inverse of an exponential. Calculate the inverse of f(x) = $2^{3x-5}$. Swap x and y (this reflect the graph across y = x) $x = 2^{3y-5}$⇒[Solve for y. Take log2 of both sides and consider that logb(ba) = a] $log_2(x) = 3y -5$ ⇒[Solve for y] $3y = log_2(x) + 5 \implies y = \frac{log_2(x) + 5}{3}$. So the inverse function is $f^{-1}(x) = \frac{log_2(x) + 5}{3}$ (Figure 1.d.) with domain x > 0 (since the original range of f is (0, ∞).

Find the inverse function based on the given graph (Figure 1.g).

To prove that two functions f and g are inverses, one needs to show that composing one function with the other gives the identity function. In other words, $f(g(x)) = x, \forall x \in Dom(g), g(f(x)) = x, \forall x \in Dom(f)$.

As it was previously stated, these are not inverses on all of $\mathbb{R}$. $f: [-5,\infty) \to [0,\infty)$, domain $[-5, \infty)$, range $[0, \infty), g:\ \mathbb{R} \to [-5,\infty)$, range $[-5, \infty)$.

To make them true inverses,we must restrict the domain of g to $[0, \infty)$ so that g maps $[0,\infty) \to [-5,\infty)$.

For $x \ge 0$, $f(g(x)) = \sqrt{x^2-5+5} = \sqrt{x} = x$ (the final equality holds because x ≥ 0). For $x \ge 5,$ $g(f(x)) = (\sqrt{x+5})^2-5 = x +5 -5 = x$. Thus, with the domain restriction $g: [0,\infty) \to[-5,\infty)$, the two functions are inverses: $f:\ [-5,\infty) \to [0,\infty), g: [0,\infty) \to [-5,\infty).$

Problem. Martha earns 8 dollars per hour for up to 40 hours per week and receives overtime (any hours beyond 40) pay at a rate of 1.5 times her regular hourly wage. If Martha earned $380 last week, how many hours did she work? (Figure vi)

Model the earnings function E(h), where h is the total hours worked. If h > 40, then $E(h) =[\text{1.5 times her regular hourly wage,} 1.5\cdot 8 = 12] 8\cdot40 + 12\cdot(h-40)=320 + 12(h-40)=12h -160$

$E(h) = \begin{cases} 8h, &0 \le h \le 40 \\\\ 12h -160, &h > 40 \end{cases}$

We are told E(h)=380. Since 380 > 320 = 8×40, she must have worked overtime, so we should use the overtime formula: 12h - 160 = 380.

Solve: $12h = 540 \implies h = \frac{540}{12} = 45$. Answer: Martha worked 45 hours (i.e., 5 overtime or extra hours).

If you view E on the domain $h \ge 40$ with E(h) = 12h - 160, then its inverse is $E^{-1}(x)=\frac{x+160}{12}$, and $E^{-1}(380)=(380+160)/12=45$.

Trigonometric functions are periodic and therefore, they are not one-to-one on $\mathbb{R}$. To obtain inverses we choose principal branches (restricted domains) to make them one-to-one.

Theorem. Derivate of the inverse functions. Let f be a bijective function that is differentiable at $x_0$, and assume $f'(x_0)\neq 0$. Then, the inverse function $f^{-1}$ is differentiable at $a = f(x_0)$ and its derivative is given by $\boxed{(f^{-1})'(a)=\frac{1}{f'(f^{-1}(a))}}$.

Equivalently, $(f^{-1})'(f(x_0))=\frac{1}{f'(x_0)}.$

Proof.

Let y = f-1(x) ↭[By definition of the inverse function, this is equivalent to] x = f(y)⇒[Differentiate both sides with respect to x. Chain Rule] $\frac{d}{dx}(x) = f'(y)·\frac{dy}{dx} \implies 1 = f'(y)·\frac{dy}{dx} \implies \frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{f'(y)}$⇒[y = f-1(x)] $(f^{-1})'(x) = \frac{1}{f'(f^{-1}(x))}$ ⇒[Evaluating at x = a] $(f^{-1})'(a) = \frac{1}{f'(f^{-1}(a))}$∎

The condition $f'(x_0) \neq 0$ is essential. If $f'(x_0) = 0$, the inverse may fail to be differentiable at $f(x_0)$. Geometrically, since the graph of $f^{-1}$ is the reflection of the graph of f across the line y = x, the slopes of their tangents at corresponding points are reciprocals.

Step 1. Verify invertibility. f’(x) = 5x4 +6x2 + 7 > 0 ⇒ f is strictly increasing and therefore, one-to-one.

Step 2. Find $f^{-1}(1)$. f(0) = 1 ⇒[f is one-to-one] f-1(1) = 0 ⇒[Apply the inverse derivative formula] $(f^{-1})'(1) = \frac{1}{f'(f^{-1}(1))} = \frac{1}{f'(f^{-1}(1))} = \frac{1}{f'(0)} = \frac{1}{7}.$

Since $f'(x)=\cos(x)$, the inverse derivative formula gives $(\arcsin(x))'=\frac{1}{\cos(\arcsin x)}$.

Using a right triangle, $\cos(\arcsin x)=\sqrt{1-x^2}$, so $(\arcsin x)'=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}, \forall x, |x| \lt 1.$

The horizontal line test is a graphical method used to determine whether a function is one-to-one and whether it is onto.