|

|

|

“Life is good and there’s no reason to think it won’t be, right until the moment when a blonde, non experienced nurse is going to insert a catheter in your penis like a Spanish matador,” Dad retorted. [···]

“Unless your name is Google, stop pretending you know everything. Unless your name is Facebook, stop sharing it because unless your name is Amazon, we are not buying it,” the class’ bully teased me once again, Apocalypse, Anawim, #justtothepoint.

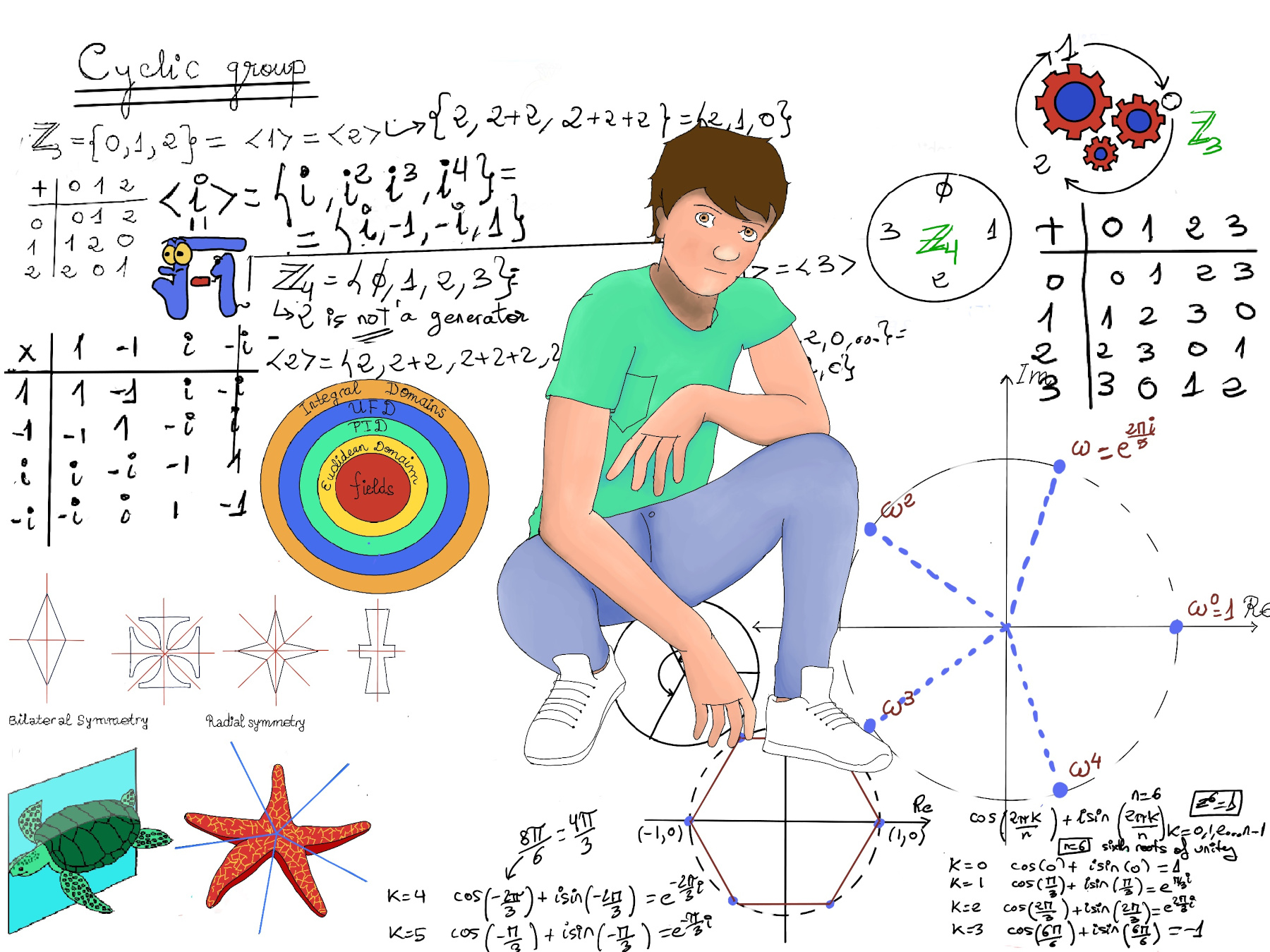

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ. A mathematical function can be thought of as a black box (or machine) that takes an input from its domain and produces exactly one output in its codomain. Inside the machine lives a specific rule (formula, procedure, or mapping) that dictates or tells you which output corresponds to each input, and a key property is uniqueness —each input maps to a single, deterministic output. No input can ever produce two different results (Figure E). The function f(x) = x2 accepts any real number x (domain: ℝ) and returns exactly one non-negative value x2 (output in codomain: [0,∞)). The input 3 always yields 9, never any other value.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

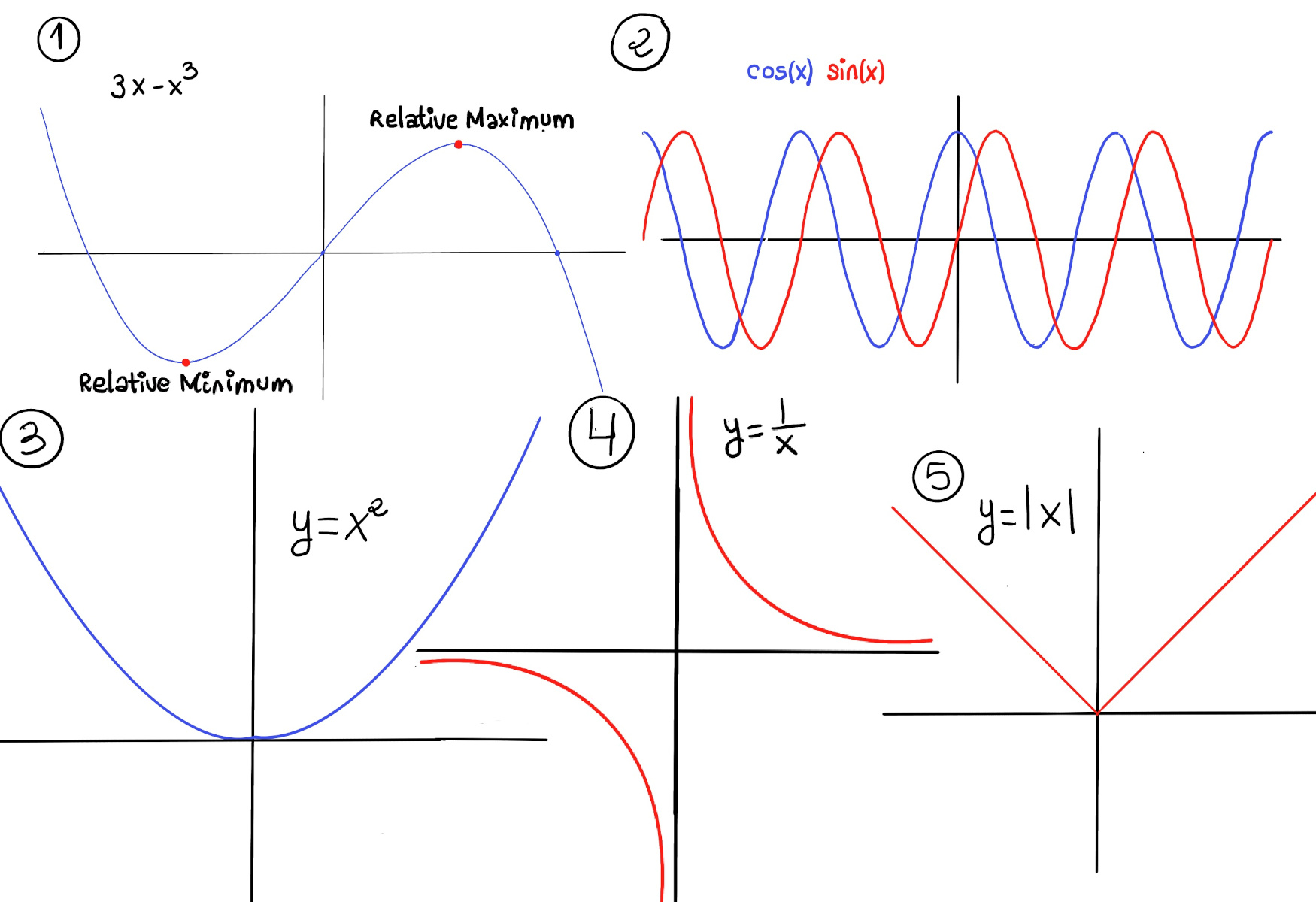

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

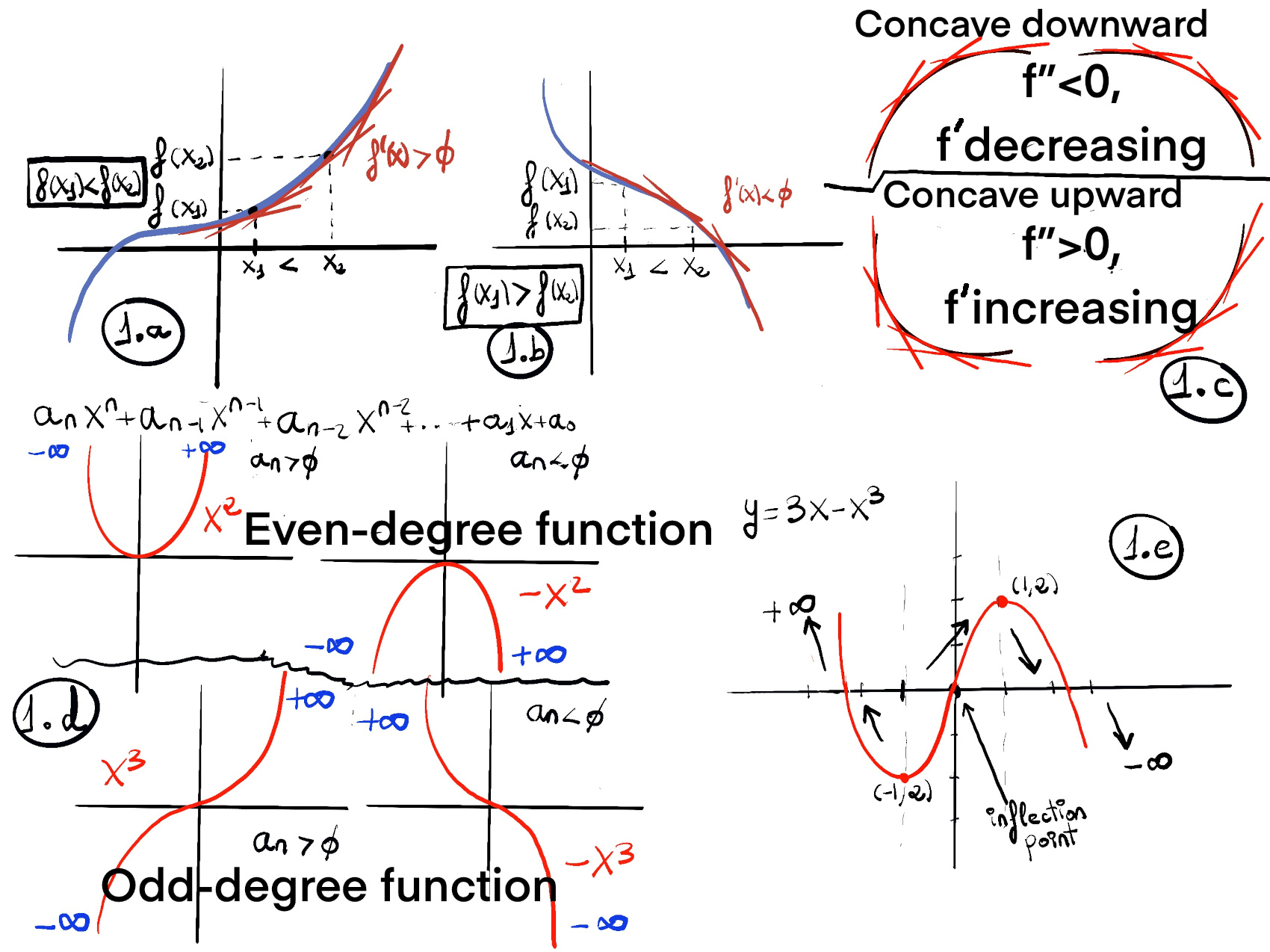

f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$.💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

First Derivative Test. Let f be differentiable on an open interval containing c, except possibly at c itself, and let c be a critical point (so f′(c) = 0 or f′ is undefined). Then:

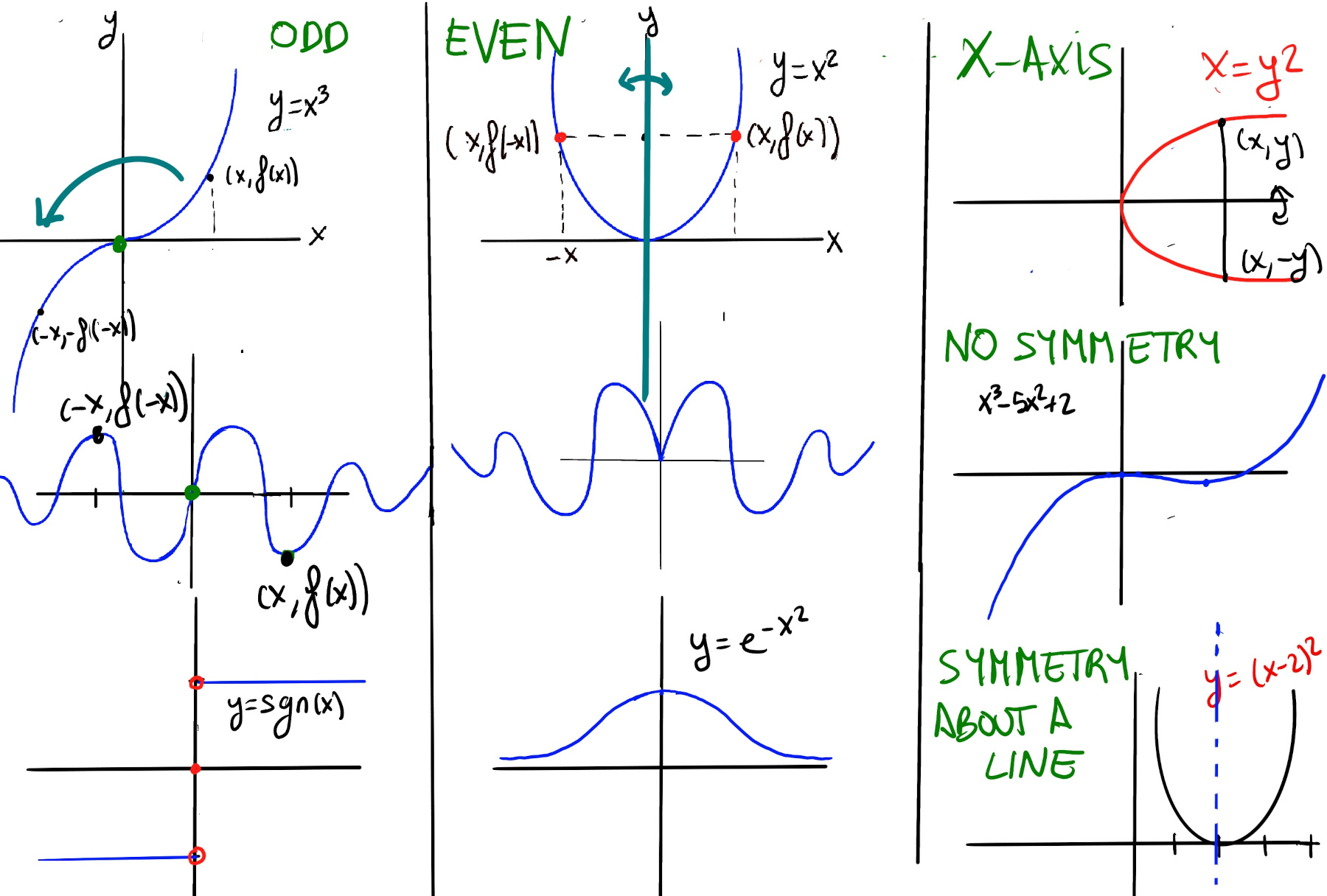

Symmetry means that a certain geometric transformation (reflection, rotation, translation) maps the graph to itself. Recognizing symmetry simplifies sketching, solving, and integrating functions. We describe the most useful types for single-variable real functions y = f(x).

A function f(x) is even if f(-x) = f(x) for every x in the domain, (x, y) = (-x, y). This condition means the graph is symmetric with respect to the y-axis. In other words, even functions allow us to view the y-axis as a mirror. If the point (x, y) lies in the graph, so does (-x, y), e.g., x2, x4, |x|, $e^{-x^2}$ -the Gaussian function- and cos(x).

Algebraic test: (1) Replace x by −x; (2) Simplify the expression; (3) If you obtain the original formula back, then the function is even. Example, f(x) = $x^2$. $f(-x) = (-x)^2=x^2 = f(x)$, then f is even.

If f and g are even, then:

All constant functions are even functions. The constant function f(x)=0 is both even and odd.

A function f(x) is odd if it satisfies f(-x) = -f(x) for every x in its domain. Geometrically, the graph of an odd function has rotational symmetry of $180\degree$ with respect to the origin. In other words, it is invariant (the graph remains unchanged) under rotation of $180\degree$ about the origin. Some examples are x, x3, sgn(x) -the sign function-, sin(x), and 1⁄x. If the point (x, y) lies on the graph, then (-x, -y) must also lie on the graph.

Another way to visualize origin symmetry is to imagine a reflection about the x-axis, followed by a reflection across the y-axis.

Algebraic test: (1) Replace x by −x; (2) Simplify the expression; (3) If the result equals the negative of the original function, -f(x), then the function f is odd, e.g., f(x) = $x^3, f(-x) = (-x)^3 = -(x)^3 = -f(x)$

If f and g are odd functions, then:

A graph is symmetric with respect to the x-axis if whenever a point (x, y) is on the graph, so is (x, -y), e.g., x = y2 ↭ y = ±$\sqrt{x}$, $x^2 + y^2 = 1$ (the unit circle). This symmetry acts like a mirror reflection over the x-axis: the upper half of the graph is a mirror image of the lower half (or vice versa).

To check if a relation (equation) has x-axis symmetry: (1) Replace y with -y in the equation. (2) Simplify. (3) If you obtain the original equation, then the graph is symmetric about the x-axis.

By definition, no single-valued function can be symmetric about the x-axis (or any other horizontal line), since anything that is mirrored around a horizontal line will violate the Vertical Line Test.

The graph is symmetric about the vertical line x = h if reflecting it across the line leaves it unchanged (invariant). For every point $(x, y)$ on the graph, the reflected point $(2h - x, y)$ must also be on the graph. This creates a “mirror image” across x = h, e.g., a parabola $y=(x-2)^2$ is symmetric about x = 2 — the axis passes through the vertex. $\cos(x-\frac{\pi}{2})$ is symmetric about the peak at $x = \frac{\pi}{2}$.

An axis of symmetry is an imaginary line that divides a figure into two identical parts that are mirror images of one another. The axis of symmetry of a parabola is the line that divides the curve into two mirror-image halves. It passes through the center of a parabola and bisects it into two equal halves.

For a quadratic $y=ax^2+bx+c$ with $a \neq 0$, the axis of symmetry (vertical line through the vertex) is $x = -\frac{b}{2a}.$ The vertex has coordinates $\Big(-\dfrac{b}{2a}, f\big(-\dfrac{b}{2a}\big)\Big)$.

How to detect it. Verify that f(h + d) = f(h - d) for all d such that both points are in the domain. This is equivalent to the function being even with respect to the shifted variable u = x - h, i.e., $f(x) = g(x - h)$ where g is even. Examples: $x^2-4x+3$ can be rewritten as $(x-2)^2-1$, the axis of symmetry is x = 2, and its vertex is (2, -1).

Even functions are symmetric about x = 0 (y-axis), so they are a special case where h = 0.

A curve has point symmetry about (h, k) if, after shifting the origin to (h, k) (i.e., defining g(x) = f(x + h) − k), the resulting function g(x) is odd, that is g(-x) = -g(x) for all x in the appropriate domain. This means the original curve is unchanged by a 180° rotation about (h, k).

$g(-x) = f(-x + h) - k, -g(x) = -(f(x + h) - k) = -f(x + h) + k$. g is odd, so $f(-x + h) - k = -f(x + h) + k \implies \boxed{f(-x + h) + f(x + h) = 2k}$. This must hold for all x (where defined).

If f itself is odd ($f(-x) = -f(x)$), then it has point symmetry about (0, 0), e.g, $x^3, \sin(x), \frac{1}{x}$.

Cubic functions $f(x) = ax^3 + bx^2 + cx + d$ ($a \neq 0$) often have point symmetry about their inflection point. The x-coordinate of the inflection (and symmetry point) is $h = -\frac{b}{3a}$ (from setting second derivative to zero: $f''(x) = 6ax + 2b = 0$). Then, $k = f(h)$.

Examples:

Some graphs do not exhibit any particular symmetry, e.g., f(x) = x3 -5x2 +2 satisfies neither f(-x) = f(x) nor f(-x) = -f(x). Keep in mind, most graphs of equations do not have symmetry across the x-axis, y-axis, or the origin, so most functions will fall into this category.

Any function f defined on a symmetric domain (i.e. if x is in domain then -x is too) can be written uniquely as the sum of an even and an odd function: $f(x) = \underbrace{\frac{f(x)+f(-x)}{2}}_{\text{even}} + \underbrace{\frac{f(x)-f(-x)}{2}}_{\text{odd}}.$

$f_{even}(−x) = \frac{f(−x)+f(−(−x))}{2} = \frac{f(−x)+f(x)}{2} =f_{even}(x), f_{odd}(−x) = \frac{f(−x)-f(−(−x))}{2} = \frac{f(−x)-f(x)}{2} =-f_{odd}(x)$

Examples:

Odd Function Examples (Symmetry about the origin): f(x) = 3x − x³. f(−x) = 3(−x) − (−x)³ = −3x − (−x³) = −3x + x³ = −(3x − x³) = −f(x) ✓ (Figure 1.e). f(x) = x³ + 5x. f(−x) = (−x)³ + 5(−x) = −x³ − 5x = −(x³ + 5x) = −f(x) ✓. They typically have only odd-powered terms like $x, x^3, x^5, \cdots $.

Even Function Example (Symmetry about the y-axis): f(x) = 3x² − 7. f(−x) = 3(−x)² − 7 = 3x² − 7 = f(x) ✓. They typically have only even-powered terms (like constants, $x^2, x^4, \cdots)$.

Equations with x-axis symmetry (like $y^2=x$, parabola opening right or $x^2+y^2=4$) fail the Vertical Line Test and therefore are not functions.

Similarly, x2 + y2 = 1 is a circle centered at the origin with radius 1 so it has symmetry about the x and y-axis, and about the origin, but it is not a function.

x -2y = 5. Test for x-axis symmetry. Replace y with −y: x -2(-y) = 5 ↭ x +2y = 5, so it is not symmetric to the x-axis.

f(x) = -4x3 +1 is neither even nor odd, no y-axis symmetry and no origin symmetry. f(-x) = -4(-x)3 +1 = 4x3 +1 ≠ f(x) and ≠ -f(x).

This is a classic example of the most common case: a cubic polynomial with both odd and even-powered terms (or a constant added to an odd function) destroys all symmetry.