|

|

|

“If you dream it you can do it” is absolutely and undeniably bullshit, wretched crap of the worst order. What cannot be cannot be, and besides witch, it’s impossible. If you can make money at what you love to do, excellent. If you cannot, understand reality, tame your dreams, search for a career path close enough to your passion, based on your education, experience, personality, talents, and skills, but still realistic and achievable, Anawim, #justtothepoint.

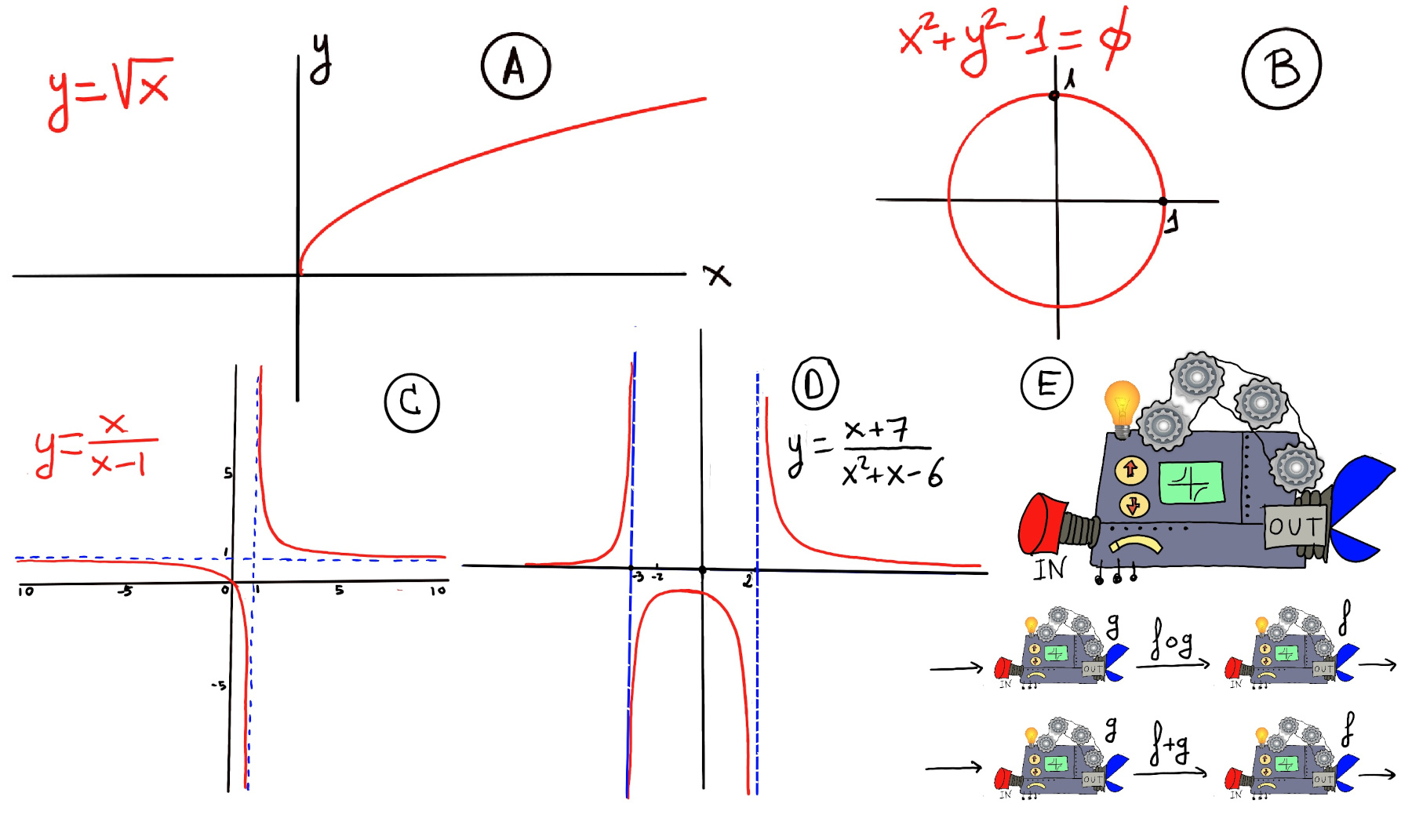

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range). A mathematical function is like a black box that takes certain input values and generates corresponding output values (Figure E).

Very loosing speaking, a limit is the value to which a mathematical function gets closer and closer to as the input gets closer and closer to some given value.

A limit describe what is happening around a given point, say “a”. It is the value that the function approaches as the input approaches “a”, and it does not depend on the actual value of the function at a, or even on whether the function is defined at “a” at all.

Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis and the understanding of how functions behave. The concept of a limit can be written or expressed as $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L.$ This notation is read as “the limit of f as x approaches a equals L”.

Intuitively, this means that the values of f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L (and I mean as close as we like, e.g., L ± 0.1, L ± 0.01, L ± 0.001, and so on), by choosing values of x sufficiently close to a, but not necessarily equal to a.

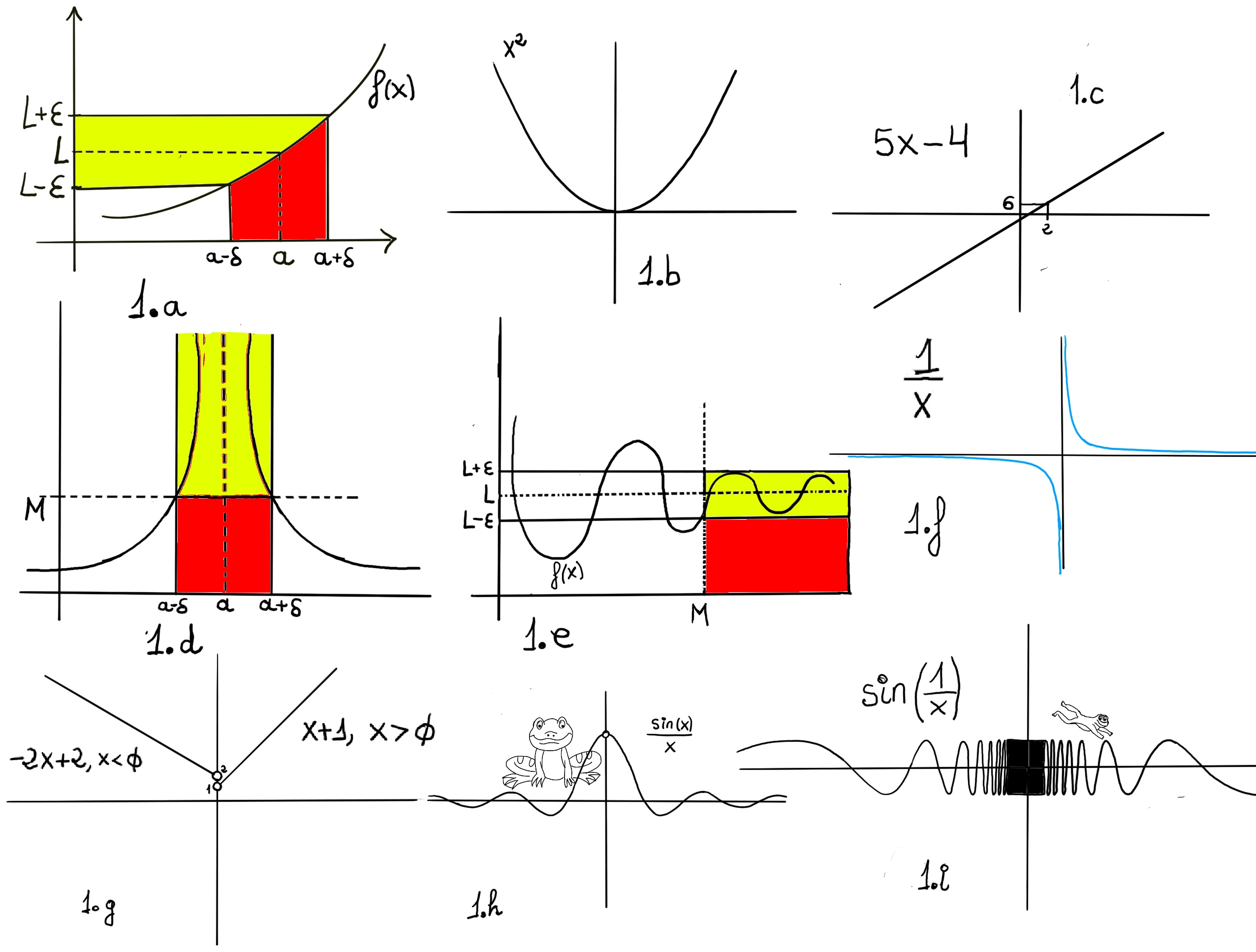

Formal definition. We say that the limit of f, as x approaches a, is L, and write $\lim_{x \to a}f(x) = L$. For every real ε > 0, there exists a real δ > 0 such that whenever 0 < | x − a | < δ we have | f(x) − L | < ε. In other words, we can make f(x) arbitrarily close to L, f(x)∈ (L-ε, L+ε) (within any distance ε > 0) by making x sufficiently close to a (within some distance δ > 0, but not equal to a) (x ∈ (a-δ, a+δ), x ≠ a) -Fig 1.a.-

Don’t worry, you are not alone. Calculating limits can be confusing and challenging for many students. But don’t worry, you are in the right place. Here are some common strategies and techniques for evaluating limits:

We have already studied some of these methods: Direct substitution, cancelling out common factors (factoring), combining fractions, the conjugate method (Rationalization), and Non-Zero Over Zero.

L’Hôpital’s Rule is a powerful calculus technique used to evaluate limits of indeterminate forms like $\frac{0}{0}$ or $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$ by taking the derivatives of the numerator and denominator separately until the limit can be solved by substitution. It states that for functions f and g which are differentiable on an open interval I except possibly at a point a ∈ I, if $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \lim_{x \to a} g(x) = 0$ or ± ∞, and g'(x) ≠ 0, ∀x ∈ $I \setminus \{ a \}$, then $\lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to a} \frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)},$ provided that the right hand (latter) limit exists or equals ± ∞.

Condition for Application: (i) Indeterminate form must be $\frac{0}{0}$ or $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$; (ii) Both f and g must be differentiable near a; (iii) The rule only applies if the limit of the derivatives exists or is infinite, then the new limit is the same as the original.

Iteration:If the result is still indeterminate, apply L’Hôpital’s Rule again to the new derivatives.

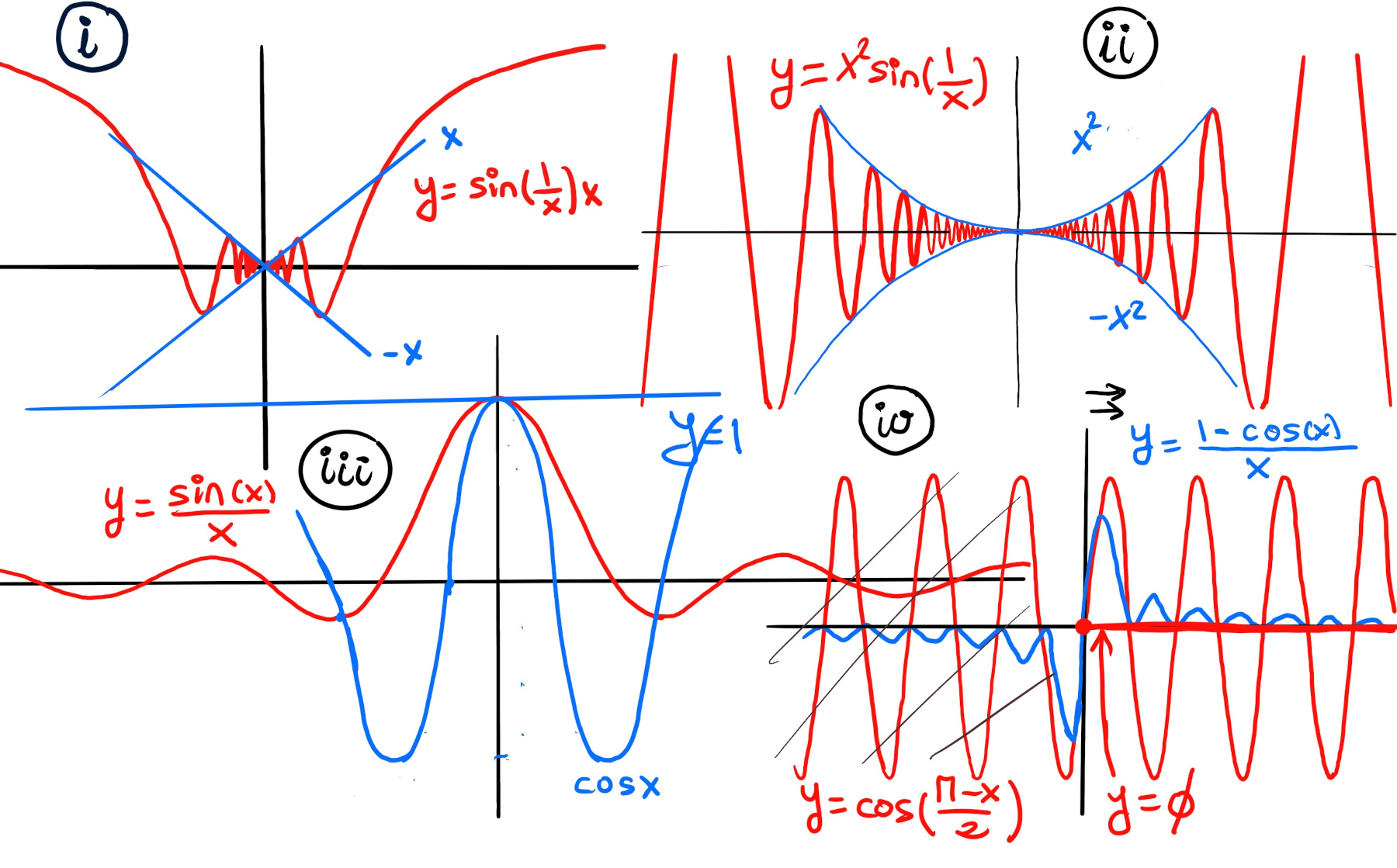

Oscillatory Example $\lim_{x \to 0} f(x), ~where~f(x)= x·sin(\frac{1}{x}) = 0$ for x ≠ 0, and f(0) = 0 (Figure i), $\lim_{x \to 0} x·sin(\frac{1}{x}) = 0$

$\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{sin(x)}{x}) = 1,$ (Figure iii)

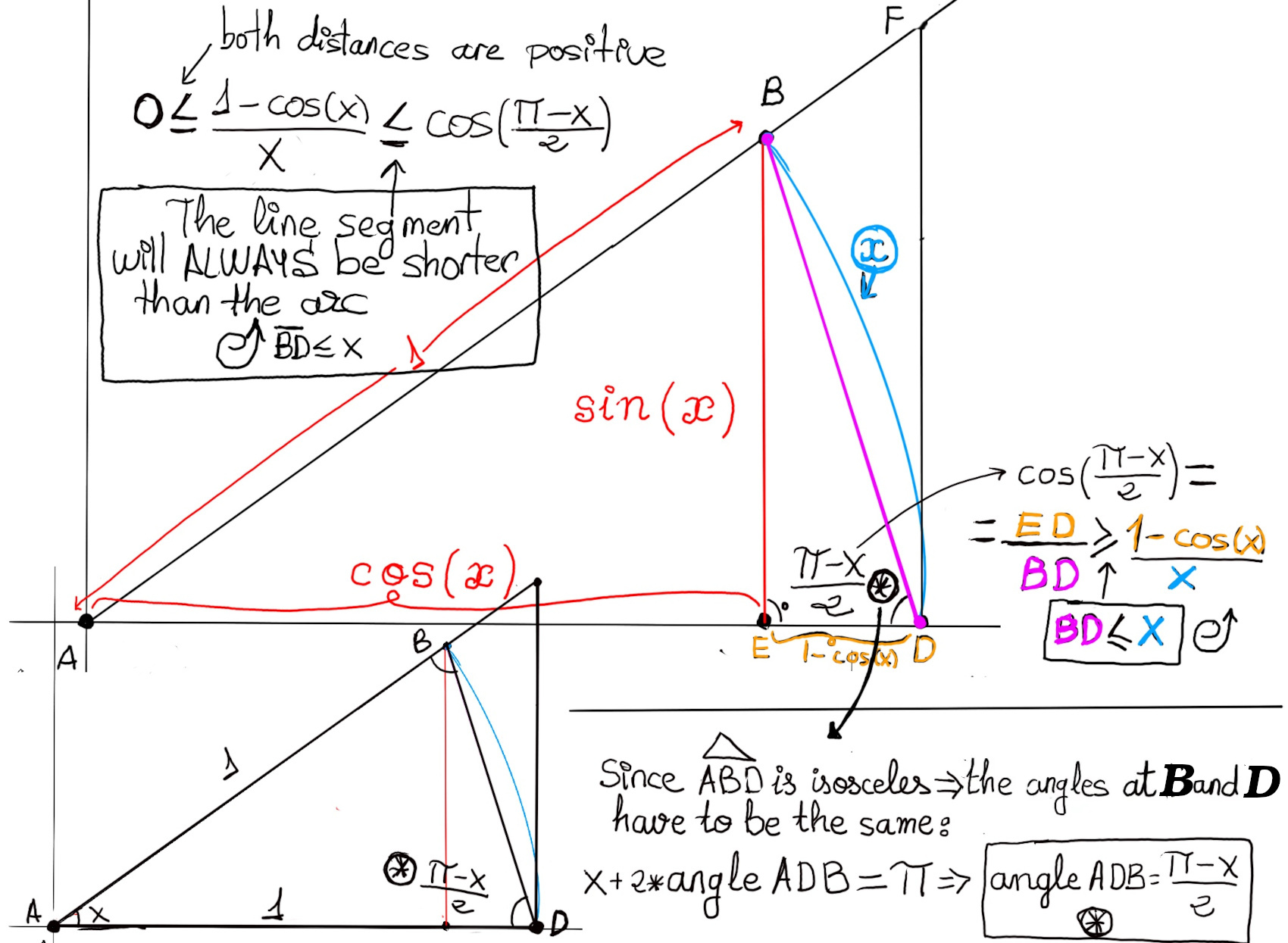

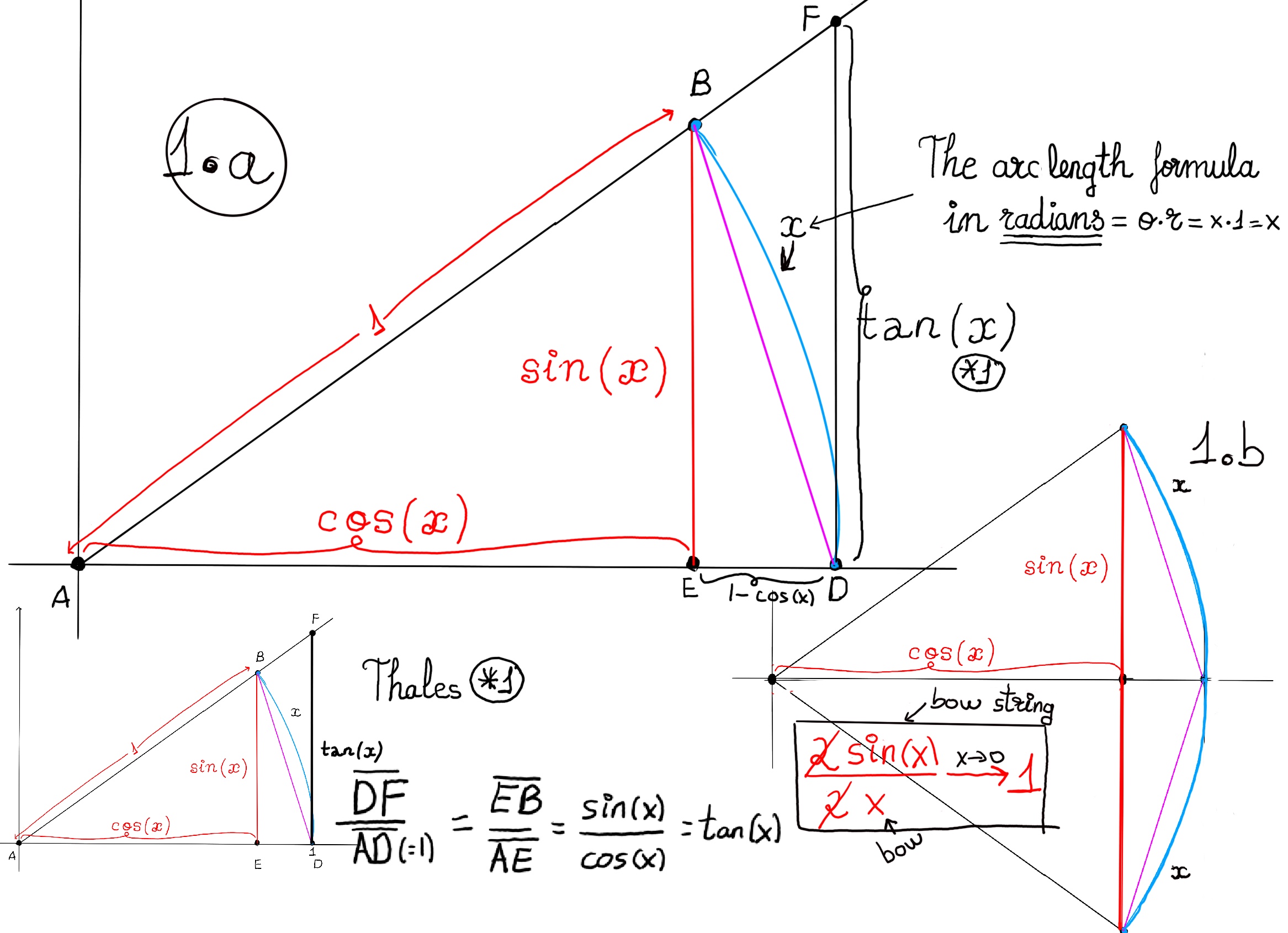

Let’s prove it geometrically. Consider the unit circle centered at the origin A with radius r = 1. Let $\theta = x$ be a small angle in radians, where $0 \lt x \lt \frac{\pi}{2}$. Point B is at (cos(x), sin(x)). The arc length of a circle in radians can be expressed as, $\text{Arc Length} = \theta·r =[r = 1] x$. In other words, the arc BD has length equal to the angle in radians, Arc Length = x.

Notice that as x→0, the bow string (chord) is the same size than the bow (arc) itself, note that if we consider a central angle of 2x (Figure 1.b), the arc length becomes 2x and the chord length is $ 2\sin(x)$. As x→0, these becomes indistinguishable, suggesting $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{2sin(x)}{2x} = \lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{sin(x)}{x}) = 1.$ However, to make this rigorous, we’ll use the squeeze theorem with area inequalities for central angle x.

We are going to work in the unit circle r = 1. Let x be an angle measured in radians, with $0 \lt x \lt \frac{\pi}{2}$. From the geometry of the unit circle, we have the following area inequality: $Area(\triangle ADF) ≥ Area(Sector ADB) ≥ Area(\triangle ADB)$

(i) Area of the sector. The Area of a circle with an angle measuring 360º is πr2. The area of a sector of angle θ (θ measured in radians) in a circle of radius r is Area of sector = $\frac{1}{2}r^2\theta$. Since r = 1 and θ = x, Area(Sector ADB) = $\frac{1}{2}x$

(ii) Area of the triangle $\triangle ADB$: $\frac{1}{2}sin(x)$

(iii) Area of the triangle $\triangle ADF$ : Using Thales’ theorem, $\frac{h_{\triangle ADF}}{sin(x)} = \frac{1}{cos(x)} \implies h_{\triangle ADF} = tan(x)$. Therefore, $A(\triangle ADF) = \frac{1}{2}\cdot 1 \cdot tan(x) = \frac{tan(x)}{2}$

Putting the three areas together: $\frac{tan(x)}{2} ≥ \frac{x}{2} ≥ \frac{sin(x)}{2}$

$[0 \lt x \lt \frac{\pi}{2}, \text{Multiplying by 2}] ⇨ \frac{sin(x)}{cos(x)} ≥ x ≥ sin(x) ⇨[\text{Now take reciprocals (which reverses inequalities because all terms are positive):}] \frac{cos(x)}{sin(x)} ≤ \frac{1}{x} ≤\frac{1}{sin(x)}$

$\frac{cos(x)}{sin(x)} ≤ \frac{1}{x} ≤\frac{1}{sin(x)}[\text{Multiply everything by sin(x)>0 for } 0 \lt x \lt \frac{\pi}{2}] ⇨ cos(x) ≤ \frac{sin(x)}{x} ≤1$

We now take limits as $x \to 0, \lim_{x \to 0} cos(x) = \lim_{x \to 0} 1 = 1$ ⇨[The Squeeze Theorem implies] $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{sin(x)}{x}) = 1.$ This holds for $0 \lt x \lt \frac{\pi}{2}$. However since, sin(x) is an odd function and cos(x) is an even function, the same inequality (in absolute value) holds for $x \to 0^-$. Therefore, the limit holds from both sides.

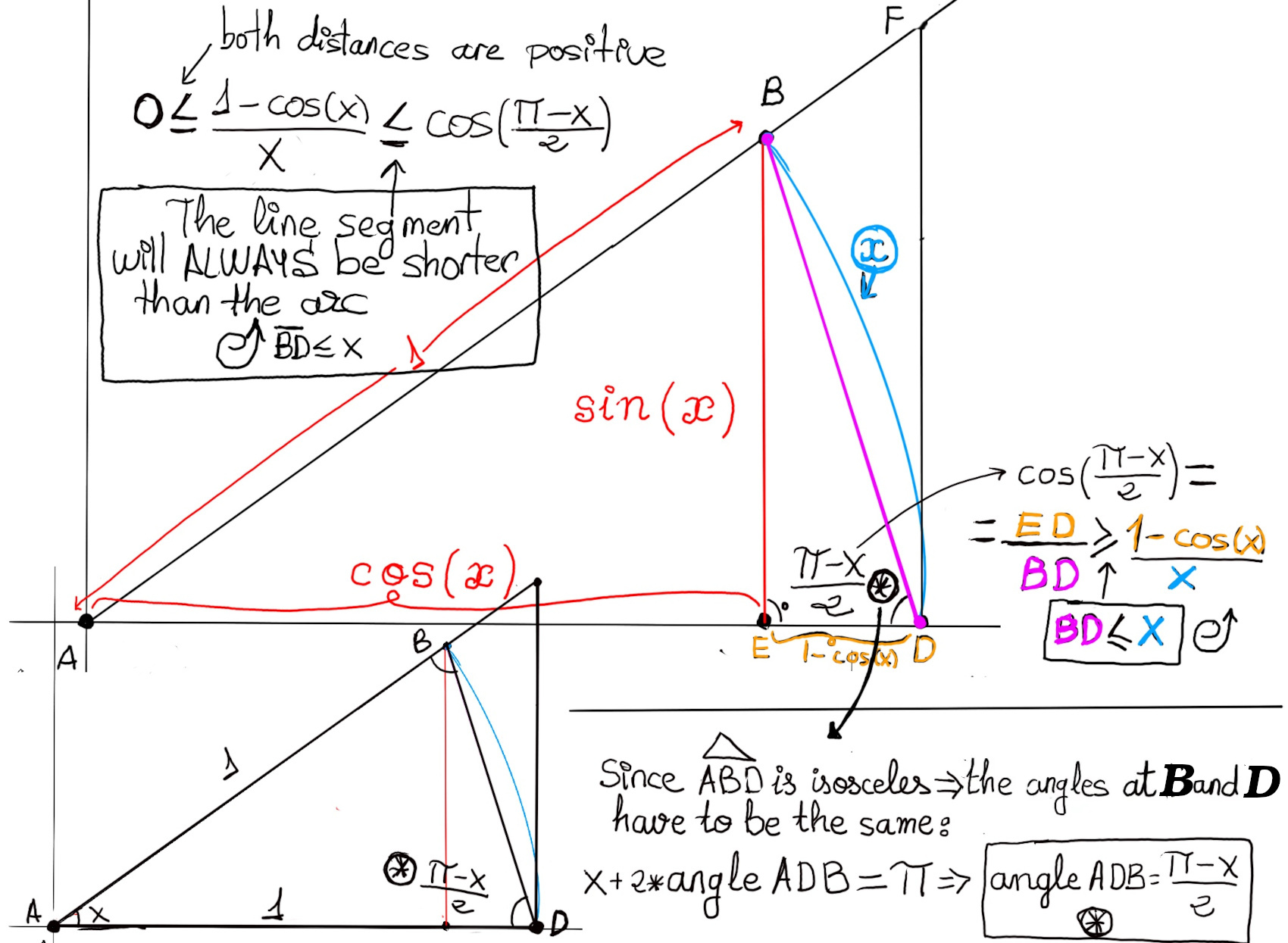

$\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{1-cos(x)}{x}) = 0,$ (Figure iv). We are working again in the unit circle (radius 1) with central angle x (in radians) between points A and B. Since $\triangle{ABD}$ is isosceles, the base angles at B and D are equal (the vertex angle at A is x, so). The sum of interior angles of a triangle is $\pi$ radians so: $x + 2\cdot \angle(ADB) = \pi \implies \angle(ADB) = \frac{\pi-x}{2}$.

An isosceles triangle is a polygon that consists of two equal sides ($\overline{AB} = \overline{AD} = 1$), two equal base angles, three sides and three vertices and the sum of internal angles equal to π radians.

Lengths involved: (i) Chord BD, This is the straight-line distance between B and D; (ii) Vertical segment $\overline{ED}$: this is the difference between the radius of the circle (y = 1) and the x-coordinate of E, which is $\cos(x)$, so $\overline{ED} = 1 -\cos(x)$.

Now look at the right triangle with hypotenuse $\overline{BD}$ and vertical leg $\overline{ED}$. The angle at D in that right triangle is exactly $\angle{ADB}=\frac{\pi -x}{2}$, so $\cos \left( \frac{\pi -x}{2}\right) =\frac{ED}{BD}$.

From geometry of the circle, the chord BD is shorter than the arc $\hat{BD}$, whose length is x (since radius = 1):

$$ \begin{aligned} \overline{BD} \le x &\implies [\text{Since ED > 0, dividing ED by both sides reverses the inequality}] \\[2pt] &\frac{\overline{ED}}{\overline{BD}} \ge \frac{\overline{ED}}{x}\\[2pt] &\implies \cos \left( \frac{\pi -x}{2}\right) \ge \frac{1-cos(x)}{x}\\[2pt] &\implies [\text{We also clearly have } \frac{1-cos(x)}{x} \gt 0] \\[2pt] &[\text{Putting all together }] \cos \left( \frac{\pi -x}{2}\right) \ge \frac{1-cos(x)}{x} \ge 0 \end{aligned} $$ $\lim_{x \to 0} cos(\frac{\pi-x}{2}) = \lim_{x \to 0} 0 = 0, \lim_{x \to 0} 0 = 0$ ⇨[By the squeeze theorem] $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{1-cos(x)}{x}) = 0.$

$\lim_{x \to 0} cos(\frac{\pi-x}{2}) = \lim_{x \to 0} 0 = 0, \lim_{x \to 0} 0 = 0$ ⇨[By the squeeze theorem] $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{1-cos(x)}{x}) = 0.$

$\lim_{x \to 0} x^2·e^{sin(\frac{1}{x})}$

$\forall x \ne 0, -1 ≤ sin(\frac{1}{x}) ≤ 1 ⇒$[The exponential is a monotone increasing function] $e^{-1} ≤ e^{sin(\frac{1}{x})} ≤ e^1 ⇒[\text{Multiplying by }x^2 \ge 0 \text{ gives: }] x^2e^{-1} ≤ x^2e^{sin(\frac{1}{x})} ≤ x^2e$

$\lim_{x \to 0} x^2e = e·\lim_{x \to 0} x^2 = e·0 = 0, \lim_{x \to 0} x^2e^{-1} = e^{-1}·\lim_{x \to 0} x^2 = e^{-1}·0 = 0$ ⇒[By the Squeeze Theorem] $\boxed{\lim_{x \to 0} x^2·e^{sin(\frac{1}{x})} = 0}.$

We use the double-angle identity for cosine: $cos(2\theta) = 1 -2sin^2(\theta)$. Let $\theta = \frac{x}{2}$. Then, $cos(x) = 1 -2sin^2(\frac{x}{2}) \implies 1 -cos(x) = 2sin^2(\frac{x}{2})$