|

|

|

Most important numbers are not 0, 1, the golden ratio, π, e, i, Graham’s number, Planck’s or Avogadro’s constant, but your ATP Pin number, your girlfriend phone number, then your mother-in-law phone number, and finally your divorce solicitor’s number, Anawim, justtothepoint.com.

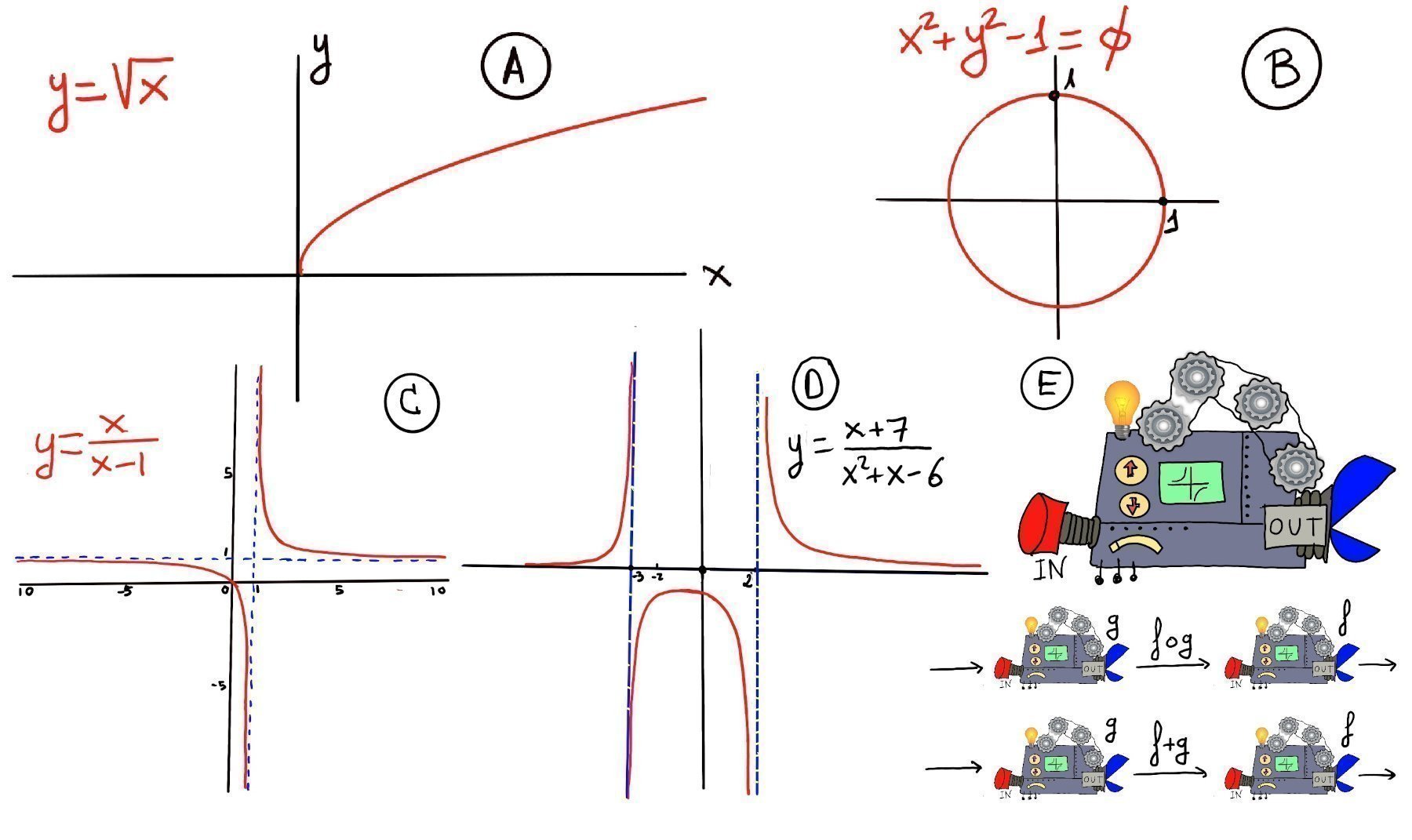

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range). A mathematical function is like a black box that takes certain input values and generates corresponding output values (Figure E).

Very loosing speaking, a limit is the value to which a mathematical function gets closer and closer to as the input gets closer and closer to some given value.

A limit describe what is happening around a given point, say “a”. It is the value that the function approaches as the input approaches “a”, and it does not depend on the actual value of the function at a, or even on whether the function is defined at “a” at all.

Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis and the understanding of how functions behave. The concept of a limit can be written or expressed as $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L.$ This notation is read as “the limit of f as x approaches a equals L”.

Intuitively, this means that the values of f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L (and I mean as close as we like, e.g., L ± 0.1, L ± 0.01, L ± 0.001, and so on), by choosing values of x sufficiently close to a, but not necessarily equal to a.

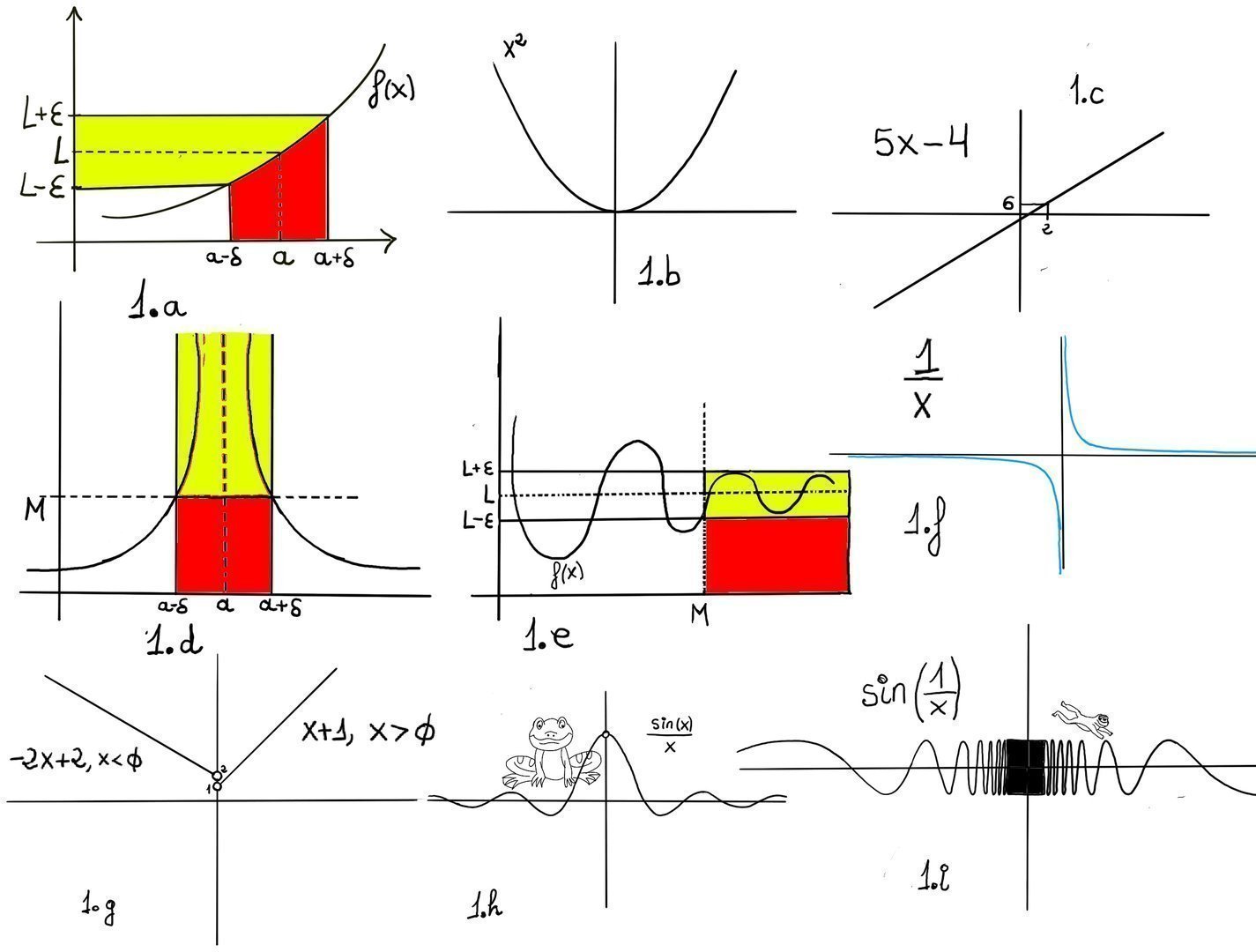

Formal definition. We say that the limit of f, as x approaches a, is L, and write $\lim_{x \to a}f(x) = L$. For every real ε > 0, there exists a real δ > 0 such that whenever 0 < | x − a | < δ we have | f(x) − L | < ε. In other words, we can make f(x) arbitrarily close to L, f(x)∈ (L-ε, L+ε) (within any distance ε > 0) by making x sufficiently close to a (within some distance δ > 0, but not equal to a) (x ∈ (a-δ, a+δ), x ≠ a) -Fig 1.a.-

The Squeeze Theorem (also called the Sandwich or Pinching Theorem) is a cornerstone of calculus and real analysis. It rigorously establishes the limit of a function by “trapping” it between two others with known, equal limits. It is especially useful for handling tricky limits when direct substitution or algebraic manipulation fails, especially those involving oscillations or indeterminate forms.

Intuitive Statement. The Squeeze Theorem helps determine the limit of a function by comparing it to two other functions whose limits are known. If f(x) is “sandwiched” between g(x) and h(x), and both g(x) and h(x) approach the same limit L as x approaches a point a, then f(x) must also approach that limit at that point.

Imagine the graph of f(x) “trapped” or “sandwiched” between g(x) and h(x), both converging to L as x gets closer to a. As x gets closer and closer to a, the “gap” between g(x) and h(x) shrinks, forcing f(x) to approach L as well.

Formal definition. Let f, g, and h be functions defined on an interval I containing x = a, except possibly at a itself. Suppose that for every x in I not equal to a ($x \ne a$), we have g(x) ≤ f(x) ≤ h(x) and $\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \lim_{x \to a} h(x) = L.$ Then, $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L.$

Proof:

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta_1>0: 0<|x-a|<\delta_1,~implies~ |g(x)-L|<\epsilon~ [*_1]$

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta_2>0: 0<|x-a|<\delta_2,~implies~ |h(x)-L|<\epsilon~ [*_2]$

Let’s choose as $\delta = min(\delta_1, \delta_2)$ $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: 0<|x-a|<\delta,~implies~$

$L -\epsilon < g(x) < L +\epsilon$ [*1] and $L -\epsilon < h(x) < L +\epsilon$ [*2]

$L -\epsilon < g(x) ≤ f(x) ≤ h(x) < L +\epsilon \implies L -\epsilon < f(x) < L +\epsilon \implies |f(x)-L|<\epsilon \implies \lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L$

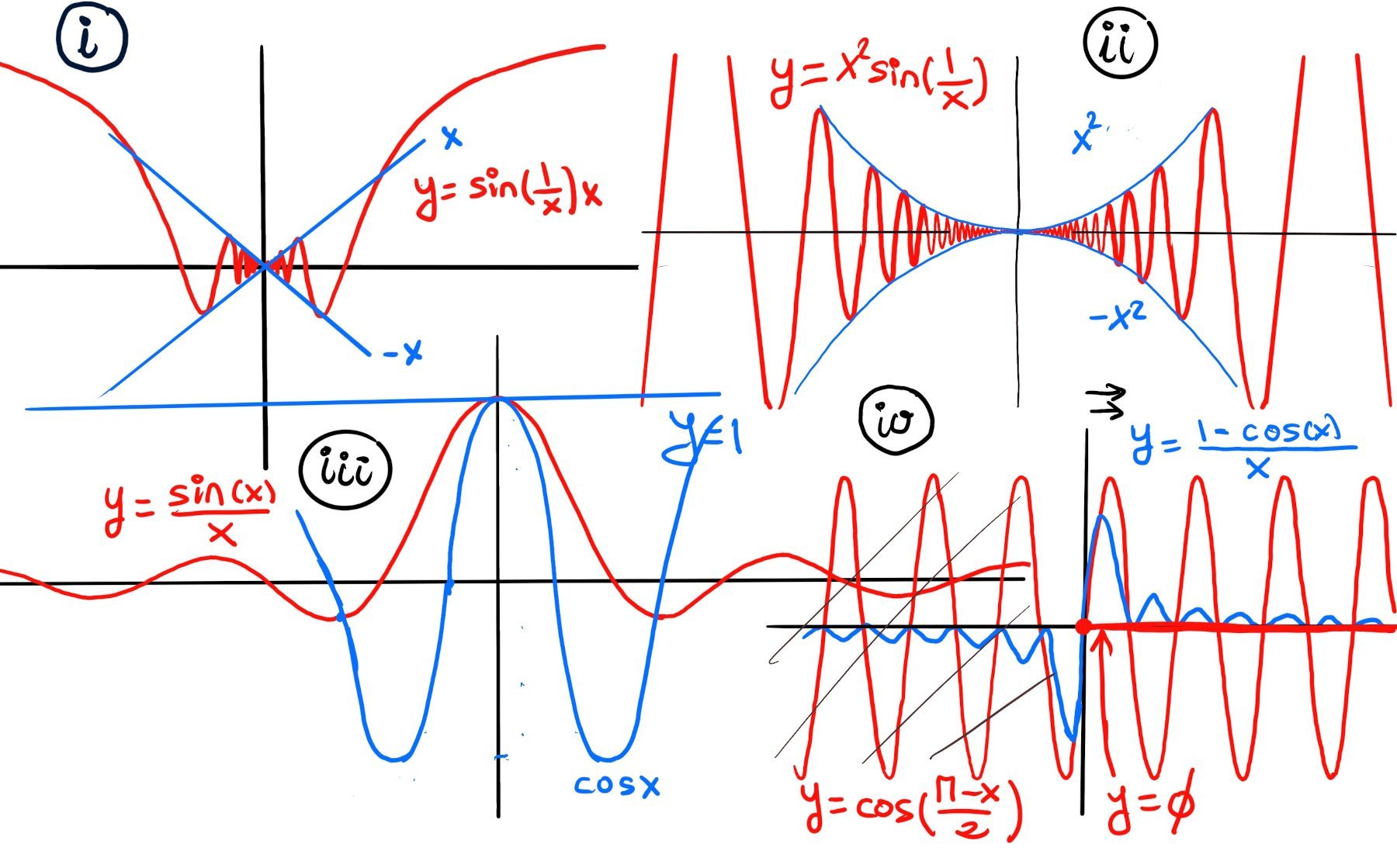

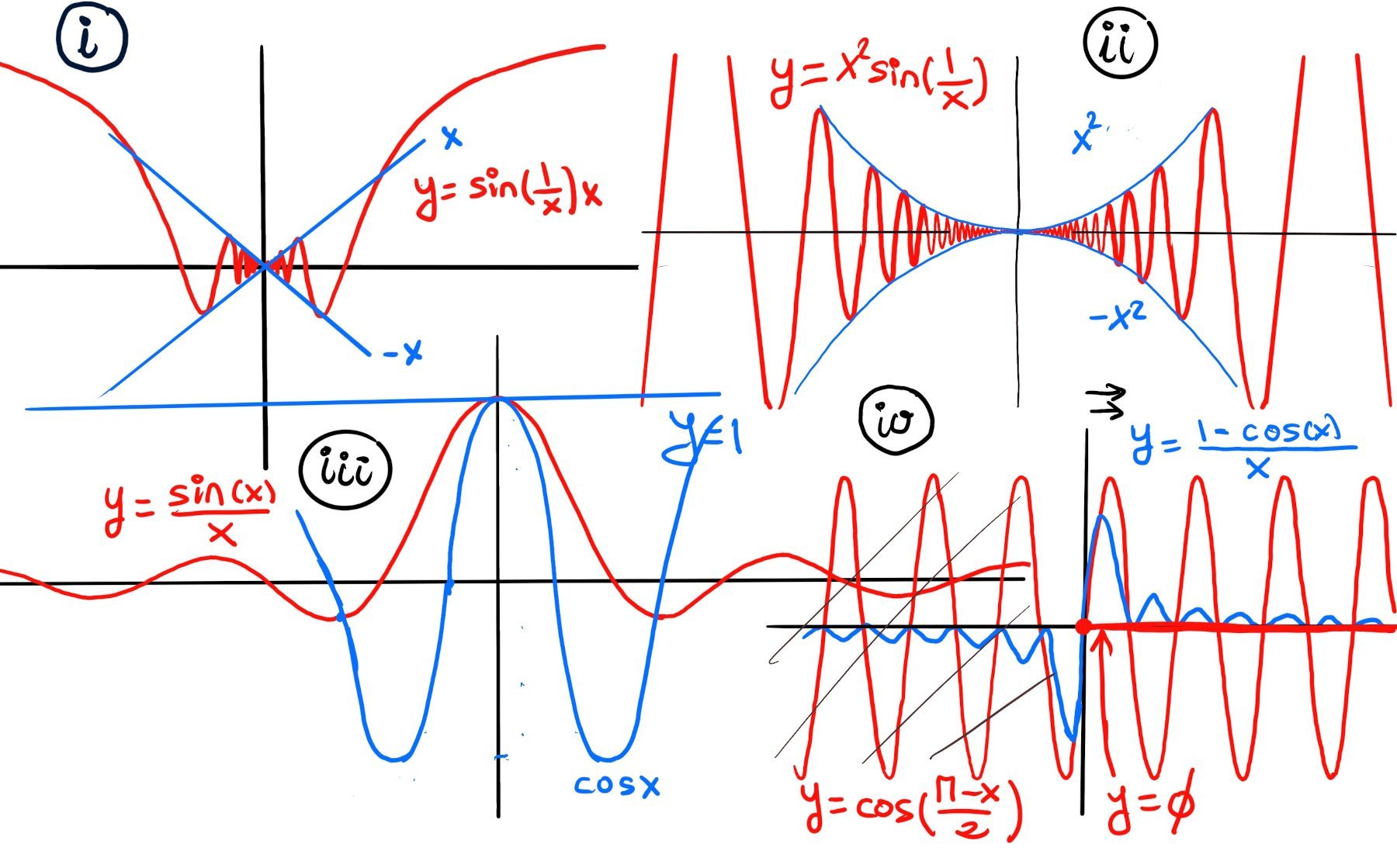

Since $-1 ≤ sin(\frac{1}{x}) ≤ 1$. Multiplying by x (considering both positive and negative x) gives: $-|x| ≤ xsin(\frac{1}{x}) ≤ |x|$

If x is a positive number, multiplying by $x$ does not flip the inequality signs, $x \cdot (-1) \le x \cdot \sin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) \le x \cdot 1 \implies -x \le x\sin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) \le x \implies$[|x| = x] $-|x| \le x\sin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) \le |x|$. If x is negative, multiplying by x flips the inequality signs, $x \cdot (-1) \ge x \cdot \sin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) \ge x \cdot 1 \implies -x \ge x\sin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) \ge x \implies x \le x\sin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) \le -x \implies$[|x| = -x] $-|x| \le x\sin\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) \le |x|$

Whether x is positive or negative, the expression $x\sin(\frac{1}{x})$ is always “trapped” between the negative magnitude of x and the positive magnitude of x.

$\lim_{x \to 0} |x| = \lim_{x \to 0} -|x| = 0.$ Then, by the Squeeze Theorem, $\lim_{x \to 0} x·sin(\frac{1}{x}) = 0$.

$-1 ≤ sin(\frac{1}{x}) ≤ 1 \implies[x^2 \ge 0] -x^{2} ≤ x^{2}sin(\frac{1}{x}) ≤ x^{2}$

$\lim_{x \to 0} x^{2} = \lim_{x \to 0} -x^{2} = 0.$ Then, by the Squeeze Theorem, $\lim_{x \to 0} x^{2} sin(\frac{1}{x}) = 0$.

$-1 ≤ cos(\frac{2}{x}) ≤ 1 \implies[x^4 \ge 0] -x^{4} ≤ x^4 cos(\frac{2}{x}) ≤ x^{4}$

$\lim_{x \to 0} x^{4} = \lim_{x \to 0} -x^{4} = 0.$ Then, by the Squeeze Theorem, $\lim_{x \to 0} x^4 cos(\frac{2}{x}) = 0$.

From basic trigonometry, -1 ≤ cos(2x) ≤ 1 ⇒ 0 ≤ cos2(2x) ≤ 1 ⇒[Since we are calculating the limit as x goes to infinity, 3 - 2x < 0 for large x; multiplying the inequality by $\frac{1}{3-2x}$ reverses the sign] $\frac{0}{3-2x}≥\frac{cos^2(2x)}{3-2x}≥\frac{1}{3-2x}⇒ \frac{1}{3-2x}≤\frac{cos^2(2x)}{3-2x}≤0$

$\lim_{x \to ∞} 0 = 0, \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{1}{3-2x} = 0 ⇒ \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{cos^2(2x)}{3-2x} = 0.$ By the squeeze theorem: $\boxed{\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{cos^2(2x)}{3-2x} = 0}.$

From basic trigonometry, -1 ≤ cos(x) ≤ 1, -1 ≤ sin(x) ≤ 1 ⇒[Cubing a number between -1 and 1 keeps it within that range] -1 ≤ cos3(x) ≤ 1 ⇒[Summing the inequalities] -2 ≤ sin(x) + cos3(x) ≤ 2 ⇒ [Since we are calculating the limit as x goes to infinity, x-3 > 0 for large x and $\frac{x^2}{x^2+1}>0$, so we can multiply by $\frac{x^2}{(x^2+1)(x-3)}$ and the inequality signs do not flip] $\frac{-2x^2}{(x^2+1)(x-3)}≤\frac{x^2(sin(x)+cos^3(x))}{(x^2+1)(x-3)}≤\frac{2x^2}{(x^2+1)(x-3)}$

$\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^2}{(x^2+1)(x-3)} = \lim_{x \to ∞}\frac{2x^2}{x^3-3x^2+x-3}$ =[Apply L’Hôpital’s rule or divide by x3 🏮] = $\lim_{x \to ∞}\frac{\frac{2}{x}}{1-3\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x^2}-3\frac{1}{x^3}} = 0$. Mutatis mutandis, $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{-2x^2}{(x^2+1)(x-3)}$ = 0, and so by the squeezing theorem, $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{x^2(sin(x)+cos^3(x))}{(x^2+1)(x-3)} = 0.$

The degree of the numerator (2) is smaller than the degree of the denominator (3). Therefore, the denominator grows much faster than the numerator, and the limit is 0.

$\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{2x^2}{(x^2+1)(x-3)} \approx \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{2x^2}{x^2 \cdot x} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{2x^2}{x^3} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{2}{x} = 0$

To evaluate the limits at infinity for a rational function, we divide the numerator and denominator by the highest power of x appearing in the denominator. This determines which term in the overall expression dominates the behavior of the function at large values of x.

We already know that $3x -1 \le 3x + sin(x) \le 3x + 1$ and also $x -1 \le x + cos(x) \le 1 + x$.

Since x > 1 ensures all expressions are positive, we obtain: $\frac{3x-1}{x+1} \le \frac{3x + sin(x)}{x + cos(x)} \le \frac{3x + 1}{x-1}$

As x→∞, both bounds tend to 3: $\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{3x-1}{x+1} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{3x + 1}{x-1} = 3$. Thus, by the Squeeze Theorem, the limit is 3, $\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{3x+sin(x)}{x+cos(x)} = 3$.