|

|

|

Extremely useful facts: 1 + 1 = 3, if you don’t use a condom. 1 + 1 = 0 in ℤ2. 4 x 4 = truck. 42 is the answer to the meaning of life, the universe, and everything else.

Extremely useful facts 2: 666 is Satan’s number. 7 is a highly spiritual number, it is mentioned numerous times in the Bible, often symbolizing completeness or perfection. 10 is the base of our number system because we have ten fingers. 13 is the most unlucky number in western civilization. Rule 34 is an internet concept meaning that if something exists in real life, or is made up, there will be an obscene or pornographic depiction of it, e.g., yes, there’s already erotic fanfic about the ship that got stuck in the Suez Canal: Rule 34 is alive and well.

Extremely useful facts 3: 69 is a sex position in which there is no intercourse. 420 has become a symbol for the consumption and celebration of marijuana. 10,213,223 is the only number that describes itself when you read it, that is, one zero, two ones, three twos, and two threes. Graham’s number is the highest number ever used in a mathematical proof.

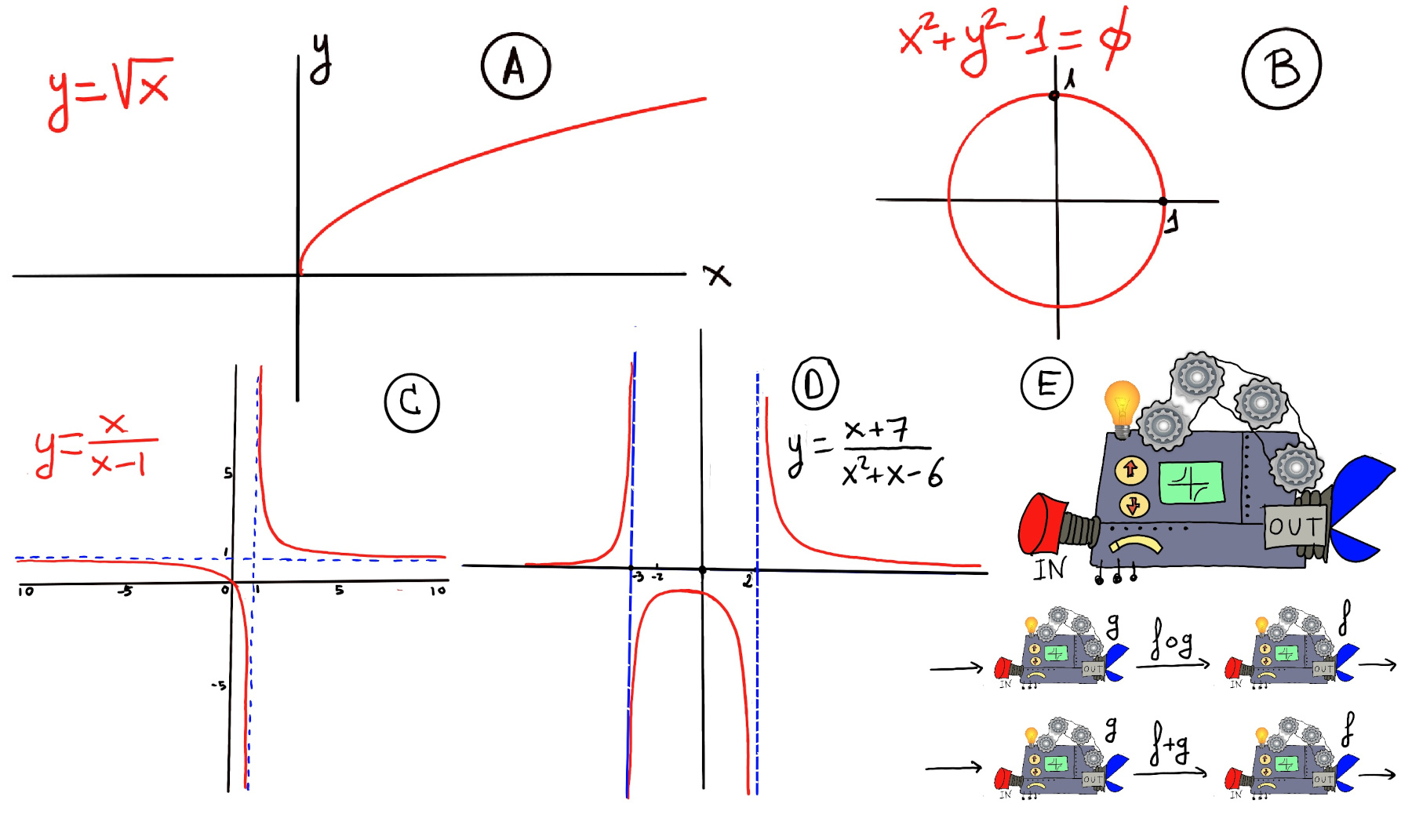

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range). A mathematical function is like a black box that takes certain input values and generates corresponding output values (Figure E).

Very loosing speaking, a limit is the value to which a mathematical function gets closer and closer to as the input gets closer and closer to some given value.

A limit describe what is happening around a given point, say “a”. It is the value that the function approaches as the input approaches “a”, and it does not depend on the actual value of the function at a, or even on whether the function is defined at “a” at all.

Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis and the understanding of how functions behave. The concept of a limit can be written or expressed as $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L.$ This notation is read as “the limit of f as x approaches a equals L”.

Intuitively, this means that the values of f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L (and I mean as close as we like, e.g., L ± 0.1, L ± 0.01, L ± 0.001, and so on), by choosing values of x sufficiently close to a, but not necessarily equal to a.

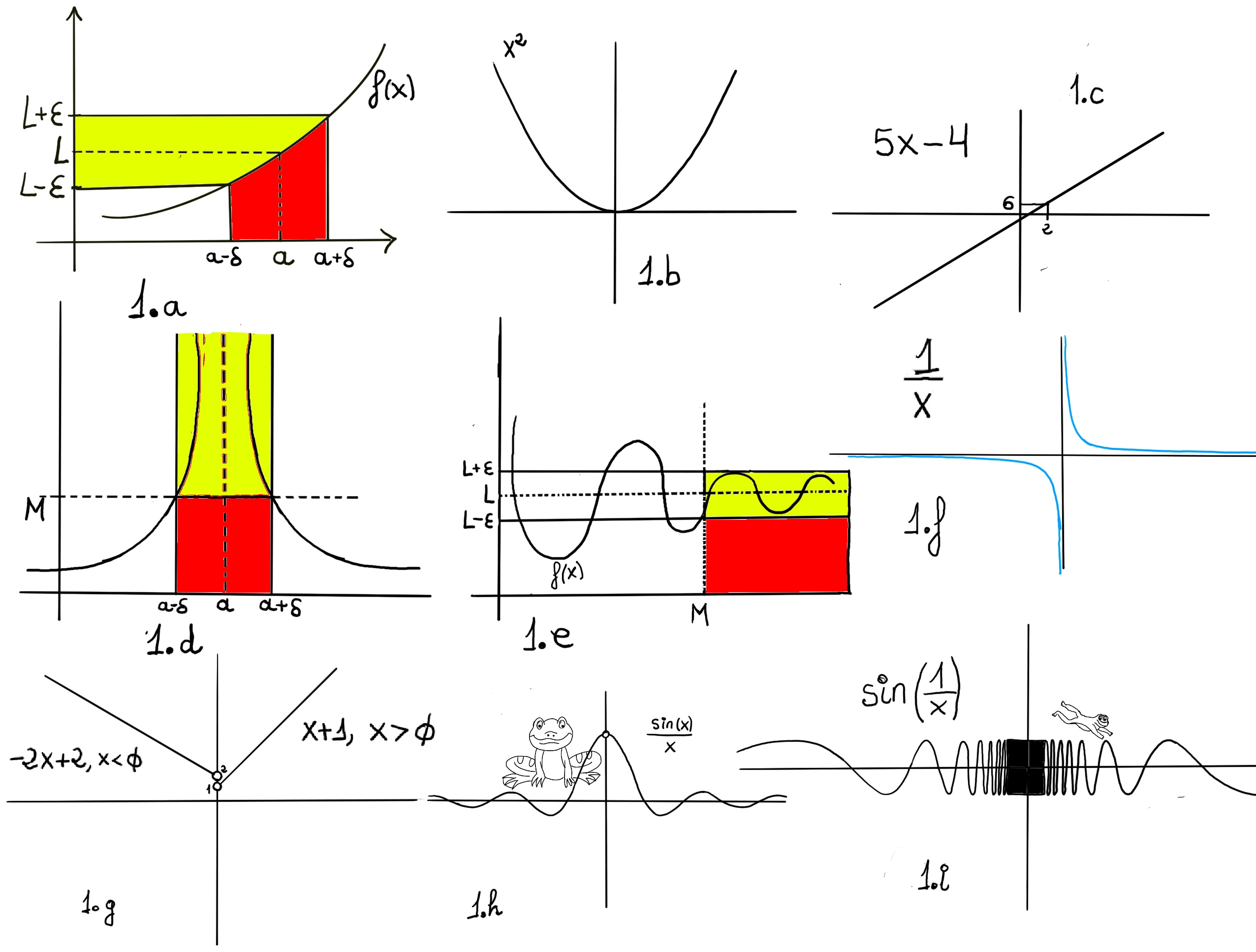

Formal definition. We say that the limit of f, as x approaches a, is L, and write $\lim_{x \to a}f(x) = L$. For every real ε > 0, there exists a real δ > 0 such that whenever 0 < | x − a | < δ we have | f(x) − L | < ε. In other words, we can make f(x) arbitrarily close to L, f(x)∈ (L-ε, L+ε) (within any distance ε > 0) by making x sufficiently close to a (within some distance δ > 0, but not equal to a) (x ∈ (a-δ, a+δ), x ≠ a) -Fig 1.a.-

One-sided limits are a refinement of the general concept of limits. They describe how a function behaves as the input approaches a given value from only one direction, either from the left or from the right.

In many real-world situations and mathematical models, what happens just before or just after a certain point matters more than what happens exactly at that point.

Informal Definition. A right-hand limit is the value L that a function approaches as x gets closer and closer to a point a from values greater than a (approaching from the right), without ever actually reaching a.

Formal definition. Let f(x) be a function defined on an interval that contains values greater than a, possibly excluding a itself. We say that, $\lim_{x \to a^{+}} f(x) = L$ if $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0:\text{ such that } 0 < x-a < \delta\, implies~ |f(x)-L|<\epsilon$

Equivalent formulations you may see: $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: a < x < a + \delta\, implies~ |f(x)-L|<\epsilon$ or simply, $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: |f(x)-L|<\epsilon, whenever~ a < x < a + \delta$.

Informal Definition. A left-hand limit is the value L that a function approaches as x gets closer and closer to a point a from values less than a (approaching from the left), without ever actually reaching a

Formal definition. Let f(x) be a function defined on an interval that contains values less than a, except possibly at a itself. We say that, $\lim_{x \to a^{-}} f(x) = L$ if $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: \text{ such that } a - \delta < x < a, implies~ |f(x)-L|<\epsilon$

Or equivalently, $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: |f(x)-L|<\epsilon, whenever~ a - \delta < x < a.$

The limit of f(x) as x approaches a exists if and only if both one-sided limits exist and are equal, that is, $\lim_{x \to a}f(x) = L \iff \lim_{x \to a^-}f(x) = L \text{ and } \lim_{x \to a^+}f(x) = L$.

When a limit does not exist, one of the following must occur:

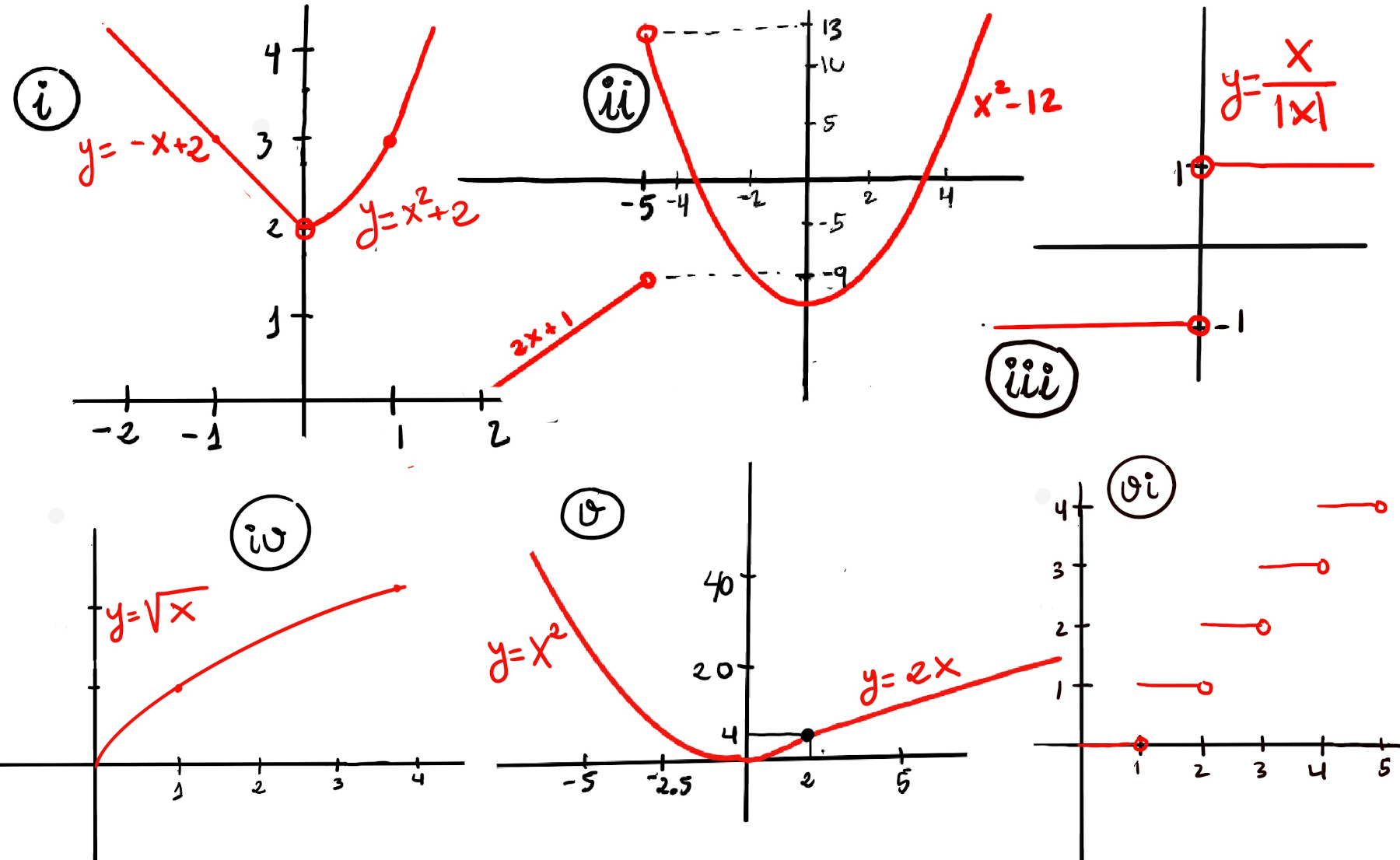

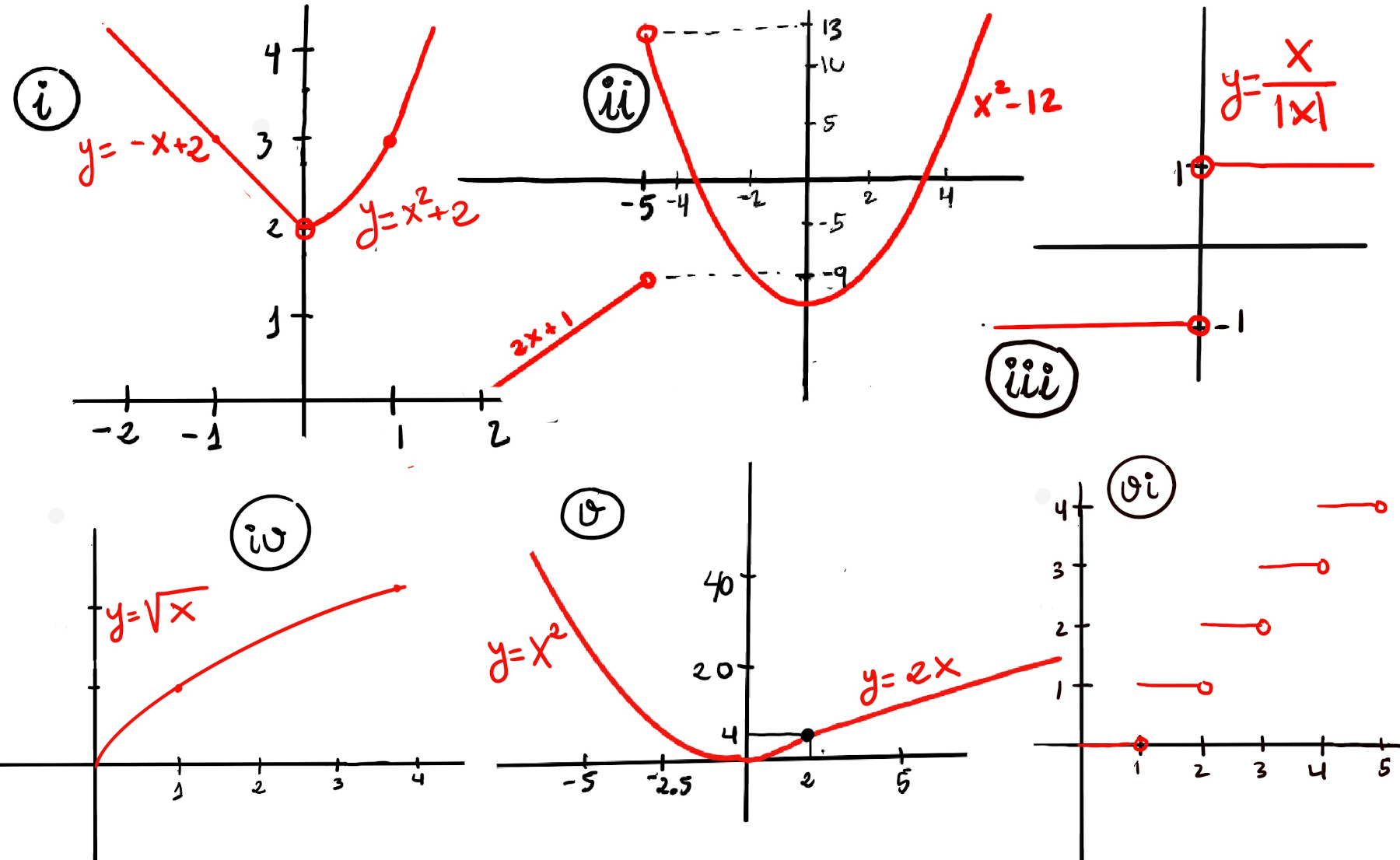

Approaching 0 from the left (x < 0), f(x) becomes -x + 2 and as we get closer and closer to 2 from the left, $\lim_{x \to 0⁻} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 0⁻} -x + 2 = 2$. Approaching 0 from the right (x > 0), f(x) becomes x2 + 2 and as we get closer and closer to 2 from the right, $\lim_{x \to 0⁺} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 0⁺} x^2 + 2 = 2.$

Since both one-sided limits agree, $\lim_{x \to 0} f(x)$ = 2, (Figure i).

Approaching 0 from the left (x < 0), f(x) becomes -2x + 2 and as we get closer and closer to 0 from the left, $\lim_{x \to 0⁻} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 0⁻} -2x + 2 = 2$. Approaching 0 from the right (x > 0), f(x) becomes x + 1 and as we get closer and closer to 0, $\lim_{x \to 0⁺} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 0⁺} x + 1 = 1$.

Since the limits are different, $\lim_{x \to 0} f(x)$ does not exist. A jump discontinuity is a type of non-removable discontinuity in a function where the left-hand limit and the right-hand limit exist but are not equal, causing the graph to have a sudden vertical jump from one value to another.

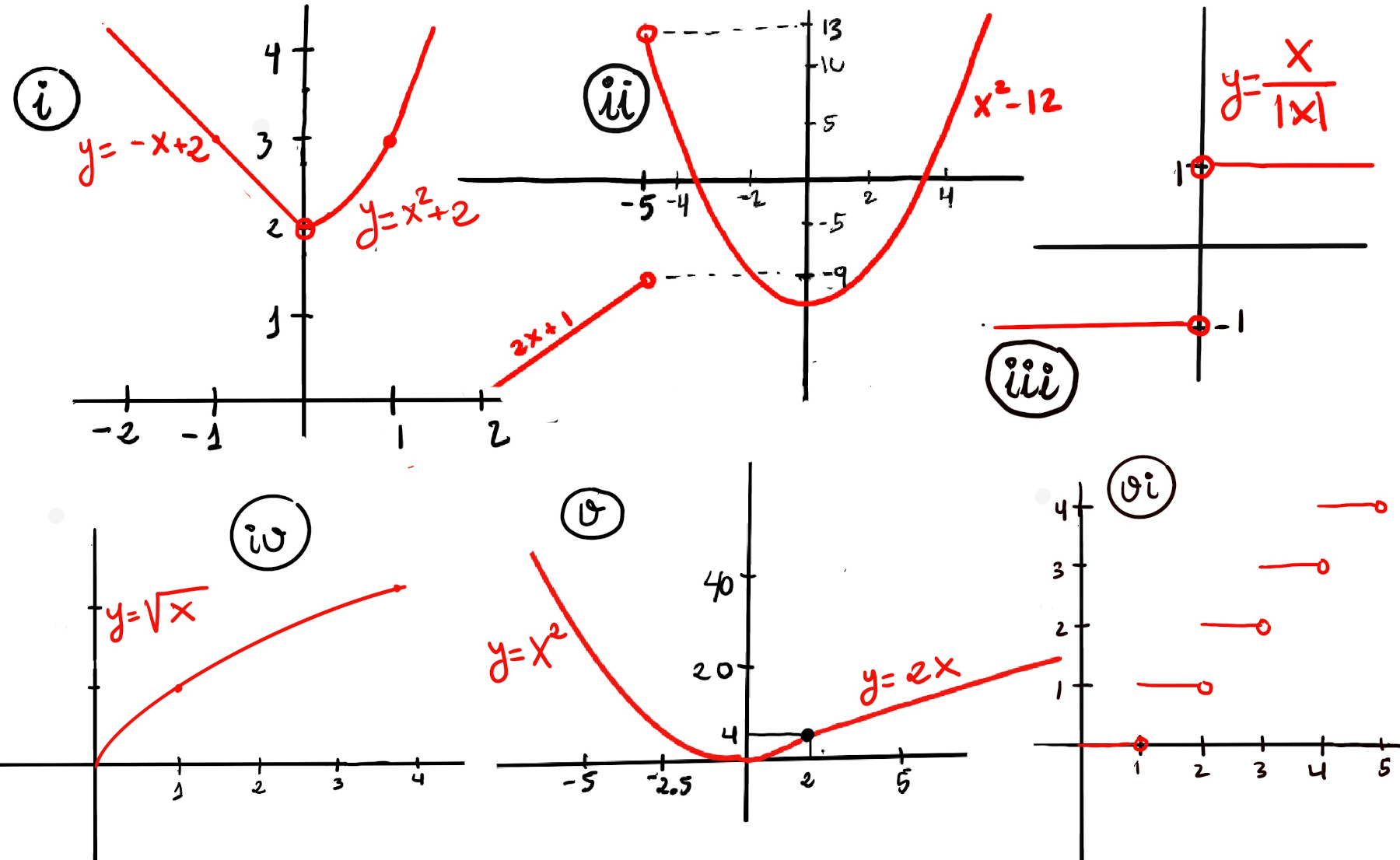

Approaching -5 from the left (x < -5), f(x) becomes 2x + 1 and as we get closer and closer to -5, $\lim_{x \to -5⁻} f(x) = \lim_{x \to -5⁻} 2x +1 = 2·-5 + 1 = -9$. Approaching -5 from the right (x > -5), f(x) becomes x2-12 and as we get closer and closer to -5, $\lim_{x \to -5⁺} f(x) = \lim_{x \to -5⁺} x^2 -12 = (-5)^2 -12 = 25 -12 = 13$.

The limit $\lim_{x \to -5} f(x)$ does not exist because the one-sided limits are different.

'''💡You can use the prompt in bing (Copilot) or chatGPT

"Write me the code in Python to plot the function

$f(x) =

\begin{cases}

2x + 1, &x < -5 \\\\

x^2 -12, &x > -5

\end{cases}$"

and then run it using an online python compile like the one provided by Online python - Codebrainy.'''

# Python code for plotting the function

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x1 = np.linspace(-10, -5, 400)

x2 = np.linspace(-5, 5, 400)

y1 = 2*x1 + 1

y2 = x2**2 - 12

plt.plot(x1, y1, 'r') # 'r' specifies red color

plt.plot(x2, y2, 'r')

plt.title('Plot of the piecewise function')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('f(x)')

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

Finding a limit by factoring is a technique to finding limits that works by canceling out common factors. It enables us to change an indeterminate form into one that can be evaluated directly. Observe that the value of the function at x = 0 (undefined) has nothing to do with the limit as x approaches 0.

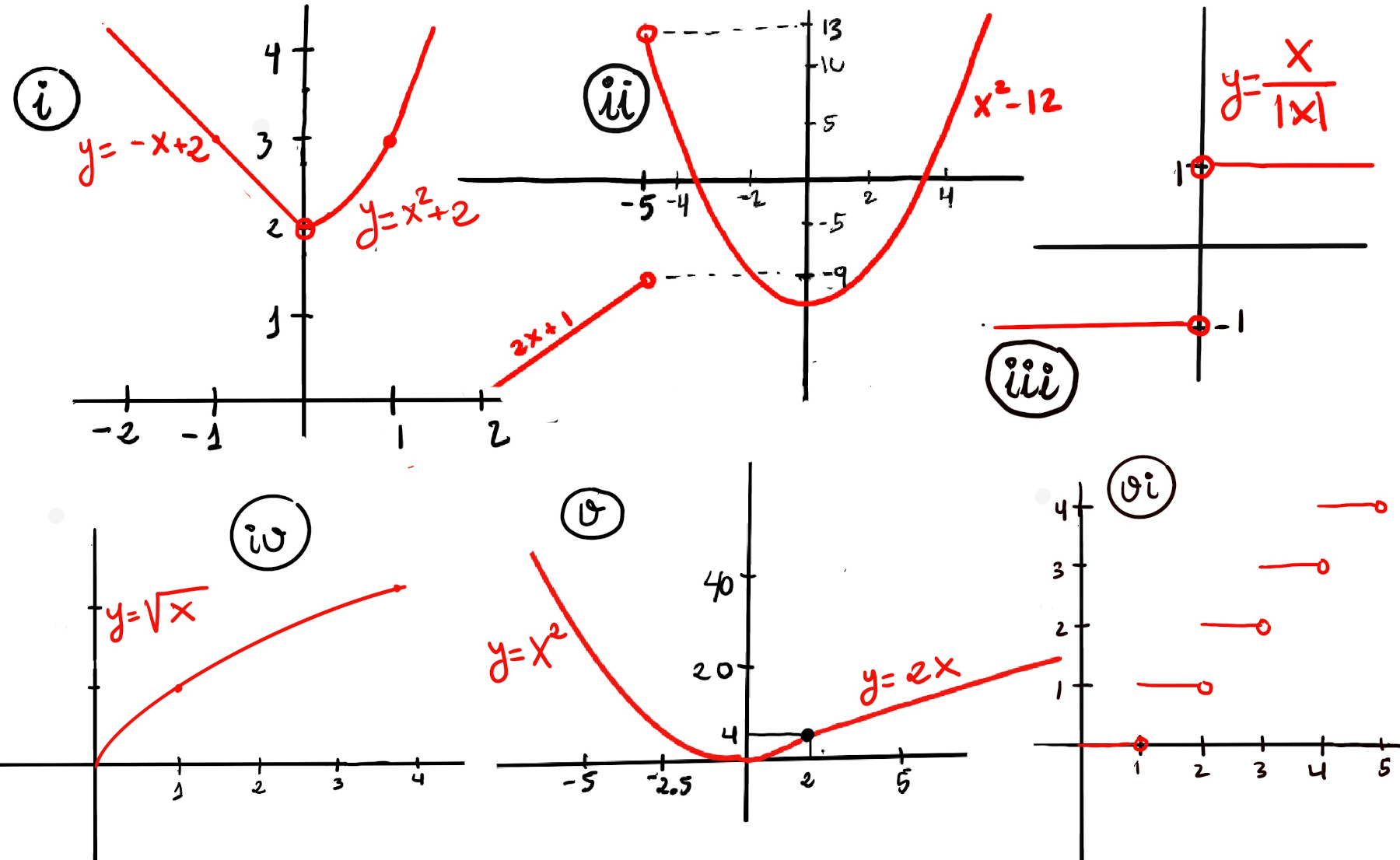

$\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{|x-2|}{x-2}$ $\lim_{x \to 2⁻} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 2⁻} \frac{-(x-2)}{x-2} = -1, \lim_{x \to 2⁺} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 2⁺} \frac{x-2}{x-2} = 1$, hence the limit $\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{|x-2|}{x-2}$ does not exist.

$f(x) = \begin{cases} x^2, &x < 2\\\\\\\\ 2x, &x ≥ 2 \end{cases}$

$\lim_{x \to 2^{+}} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 2^{+}} 2x = 4.$ $\lim_{x \to 2^{-}} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 2^{-}} x^2 = 4.$ The overall limit as x approaches 2 exists and is equal to 4, $\lim_{x \to 2^{+}} f(x) = 4$ (Figure v).

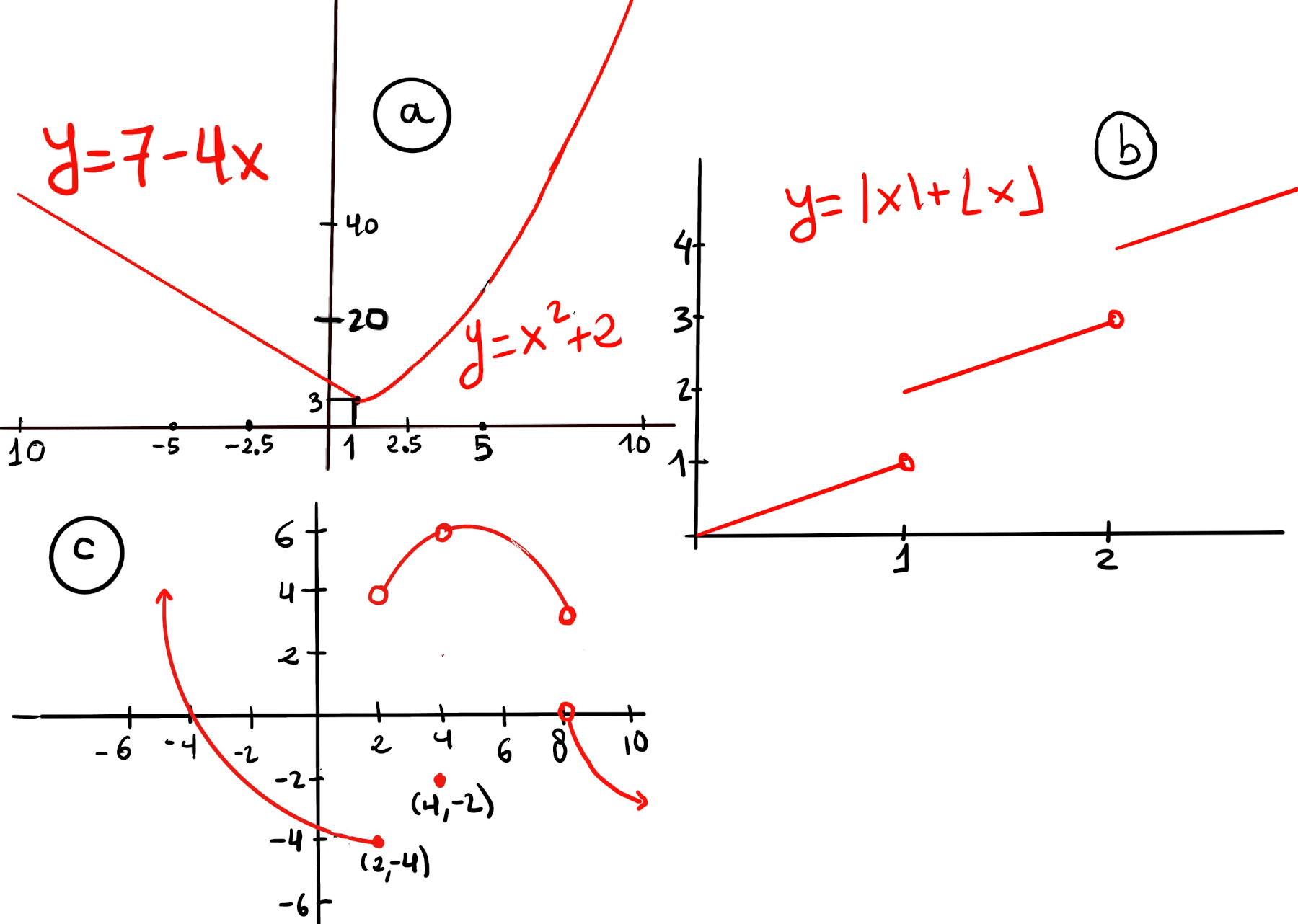

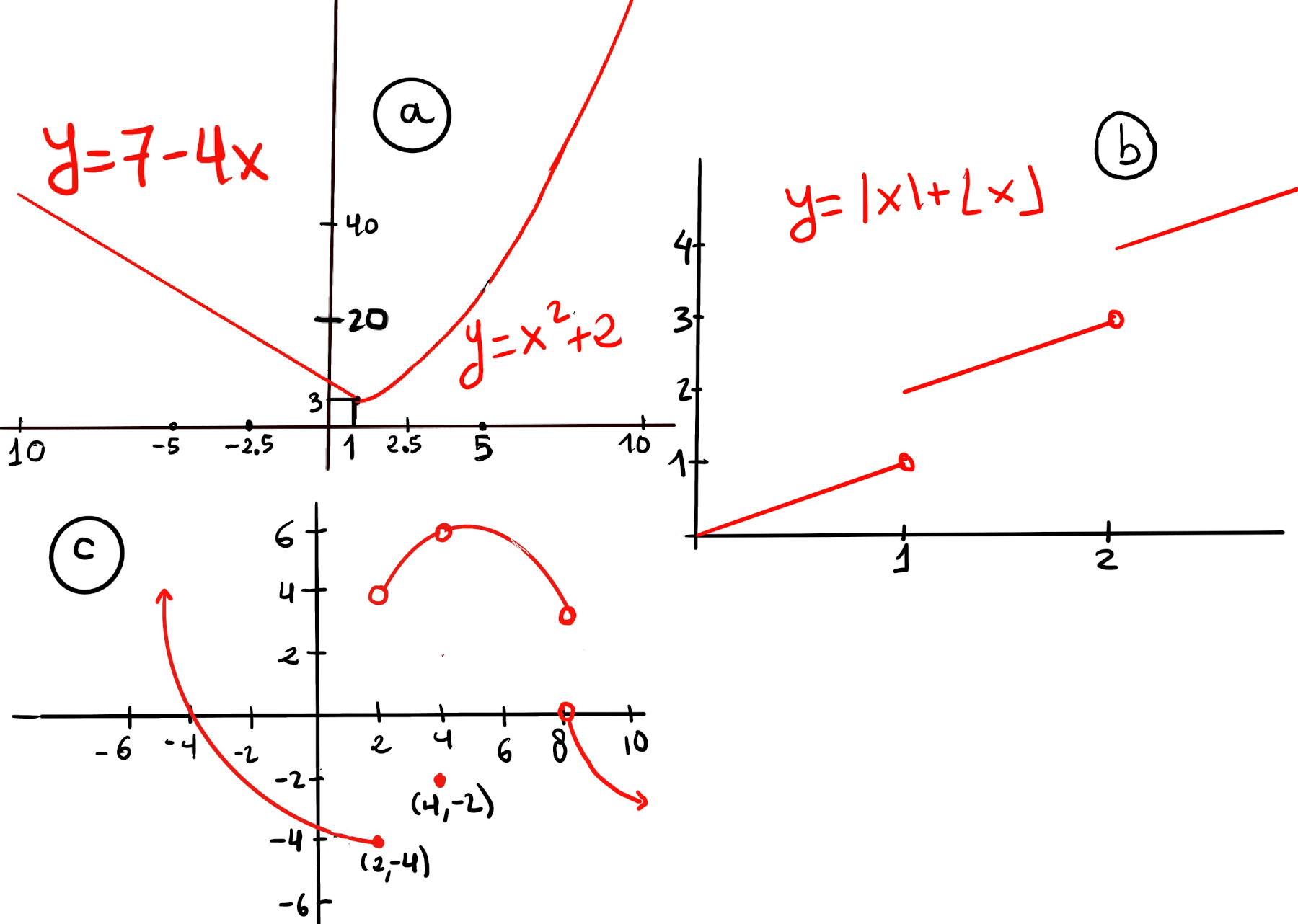

$\lim_{x \to 1⁻} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 1⁻} 7 -4x = 7 -4 = 3, \lim_{x \to 1⁺} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 1⁺} x^2 + 2 = 1 + 2 = 3 $, hence $\lim_{x \to 2} f(x) = 3$ (Figure a).

Step functions are piecewise constant functions that change values only at specific points, often at integers. They are discontinuous at these jump points, making their limit behavior particularly interesting to analyze. The most common examples are the floor function and ceiling function.

As x approaches 4 from the left, x is slightly less than 4 (e.g., 3.999), so ⌊x⌋ = 3. As x approaches 4 from the right, x is slightly greater than 4 (e.g., 4.001), so ⌊x⌋ = 4.

$\lim_{x \to 4⁻} f(x) = 3, \lim_{x \to 4⁺} f(x) = 4$. Since the one-sided limits are not equal, the two-sided limit does not exist: $\lim_{x \to 4} ⌊x⌋$ does not exist (Figure vi). This behavior is characteristic of the floor function at every integer: the left-hand limit is n−1 and the right-hand limit is n at x = n.

The greatest integer function, also know as the floor function and denoted as ⌊x⌋, gives the largest integer less than or equal to the input number, effectively rounding down to the nearest whole number, e.g., ⌊5.4⌋ = 5 (round down to nearest integer), ⌊7⌋ = 7 (integer values remain unchanged), and ⌊-2.3⌋ = -3.

$\lim_{x \to 2⁻} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 2⁻} x + ⌊x⌋ = 2 + 1 = 3, \lim_{x \to 2⁺} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 2⁺} x + ⌊x⌋ = 2 + 2 = 4 $, hence $\lim_{x \to 2} |x| + ⌊x⌋$ does not exist (Figure b).

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: |\sqrt x - 0| = \sqrt{x} <\epsilon, whenever~ 0 < x < \delta.$

We want $\sqrt{x} <\epsilon$. Since both sides are positive, squaring gives $x \lt \epsilon^2$. This suggest choosing $\delta = \epsilon^{2}$

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: 0 < x < \delta = \epsilon^{2}, then~ |\sqrt x| < \sqrt{\delta} = \sqrt{\epsilon^{2}} = \epsilon.$

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: |\frac{x+|x|}{x}-2|<\epsilon, whenever~ 0 < x < \delta$

$|\frac{x+|x|}{x}-2| =$[x > 0] $|\frac{x+x}{x}-2| = |2-2| = 0 < ε$

Since the function is identically 2 for all x > 0, the condition holds automatically regardless of δ. We may choose any positive δ (e.g., δ = ϵ for simplicity).

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: |\frac{x+|x|}{x}|<\epsilon, whenever~ -\delta < x < 0$.

$|\frac{x+|x|}{x}| =$[x < 0] $|\frac{x-x}{x}| = 0< \epsilon$.

Again, the function is identically 0 for all x<0, so any δ > 0 (e.g., δ = ϵ for simplicity) works.

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: |\frac{x^2-4}{x-2} -4|<\epsilon, whenever~ 0 < x -2 < \delta$.

$|\frac{x^2-4}{x-2} -4| = |\frac{(x-2)(x+2)}{(x-2)} -4| =[x \ne 2] | x + 2 - 4| = |x -2|$. We want ∣x − 2∣ < ϵ. This directly suggests choosing δ = ϵ.

We need to show $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: |\sqrt{1-x}|<\epsilon, whenever~ 0 < 1 - x < \delta$.

We want $|\sqrt{1-x}|<\epsilon$. Squaring (both sides positive) yield $1 - x \lt \epsilon^2$. This suggests choosing $\delta = \epsilon^2$

We need to show $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: |\frac{|x|}{x} - 1|<\epsilon, whenever~ 0 < x < \delta$.

Assume 0 < x < δ, then $|\frac{|x|}{x} - 1| = |\frac{x}{x}-1| = 0 \lt \epsilon$, any δ > 0 would do, e.g., δ = ϵ or δ = 1 (for simplicity).