|

|

|

You have to be Odd, to be number one. Copy from one, it’s plagiarism; copy from three or more, it’s research.

American actress Ilka Chase enjoyed success as a novelist. In one encounter, an anonymous actress said to her: “I enjoyed reading your book. Who wrote it for you?” …to which Chase replied: “Darling, I’m so glad that you liked it. Who read it to you?”

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ. A mathematical function can be thought of as a black box (or machine) that takes an input from its domain and produces exactly one output in its codomain. Inside the machine lives a specific rule (formula, procedure, or mapping) that dictates or tells you which output corresponds to each input, and a key property is uniqueness —each input maps to a single, deterministic output. No input can ever produce two different results (Figure E). The function f(x) = x2 accepts any real number x (domain: ℝ) and returns exactly one non-negative value x2 (output in codomain: [0,∞)). The input 3 always yields 9, never any other value.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$.💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

First Derivative Test. Let f be differentiable on an open interval containing c, except possibly at c itself, and let c be a critical point (so f′(c) = 0 or f′ is undefined). Then:

Definition. An exponential function is a mathematical function of the form f(x) = b·ax, where the independent variable is the exponent, and a and b ($b\neq 0$, we want only nontrivial functions) are constants. a is called the base of the function and it should be a positive real number (a > 0).

For a = 1, we could treat it separately as a degenerate exponential, which is just the constant function f(x) = b. We normally want “exponential” to mean “genuinely growing or decaying” rather than just a constant function.

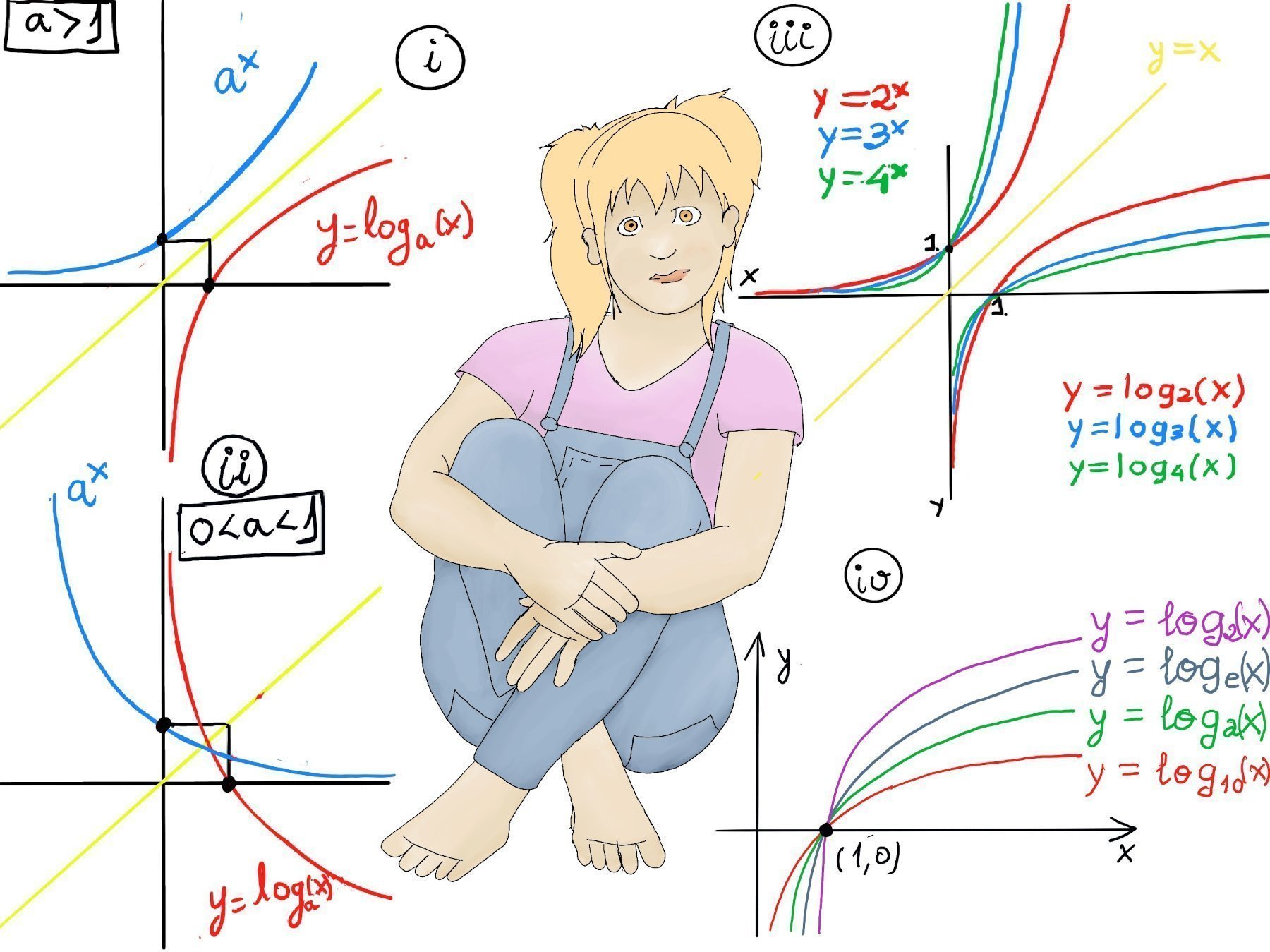

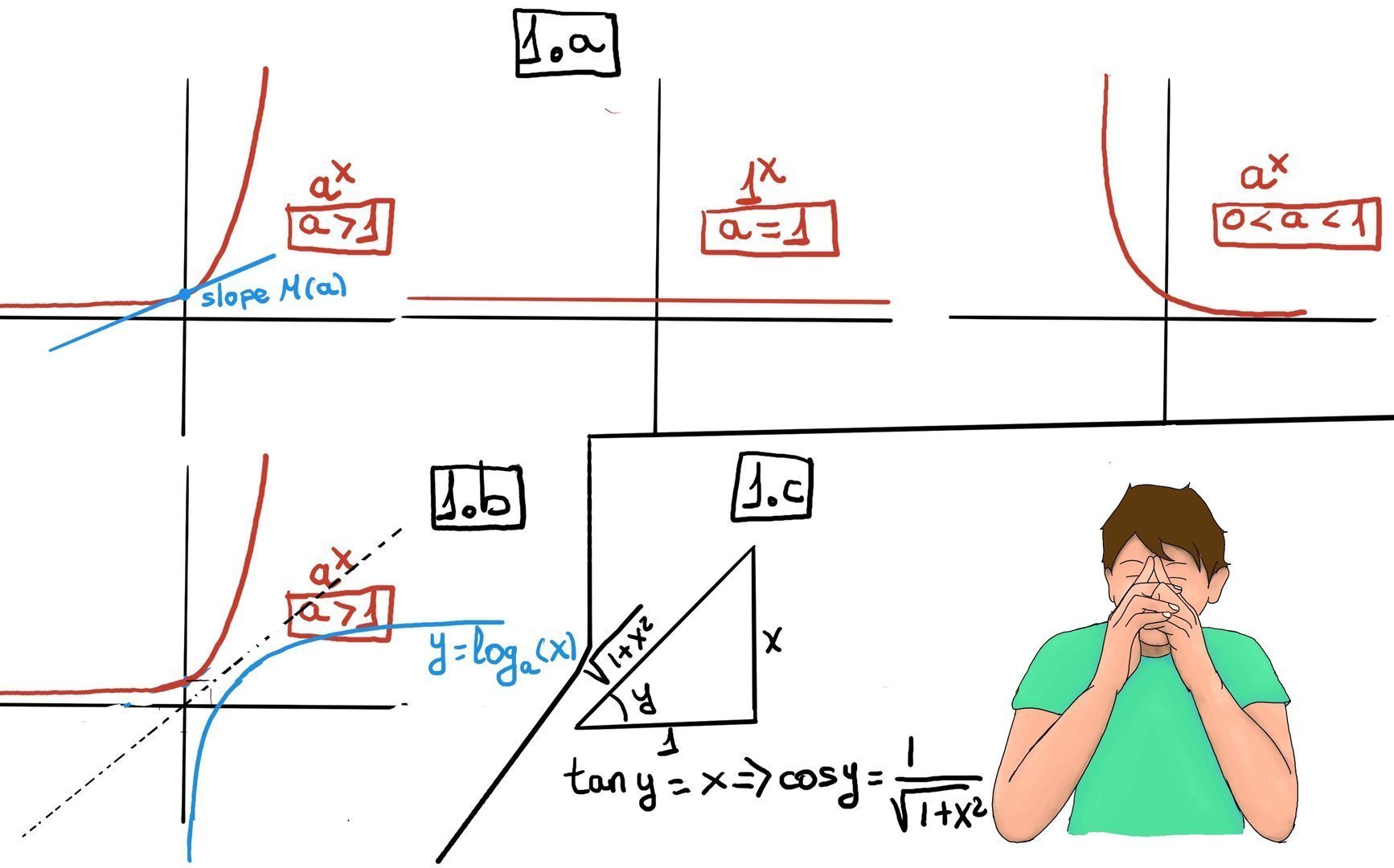

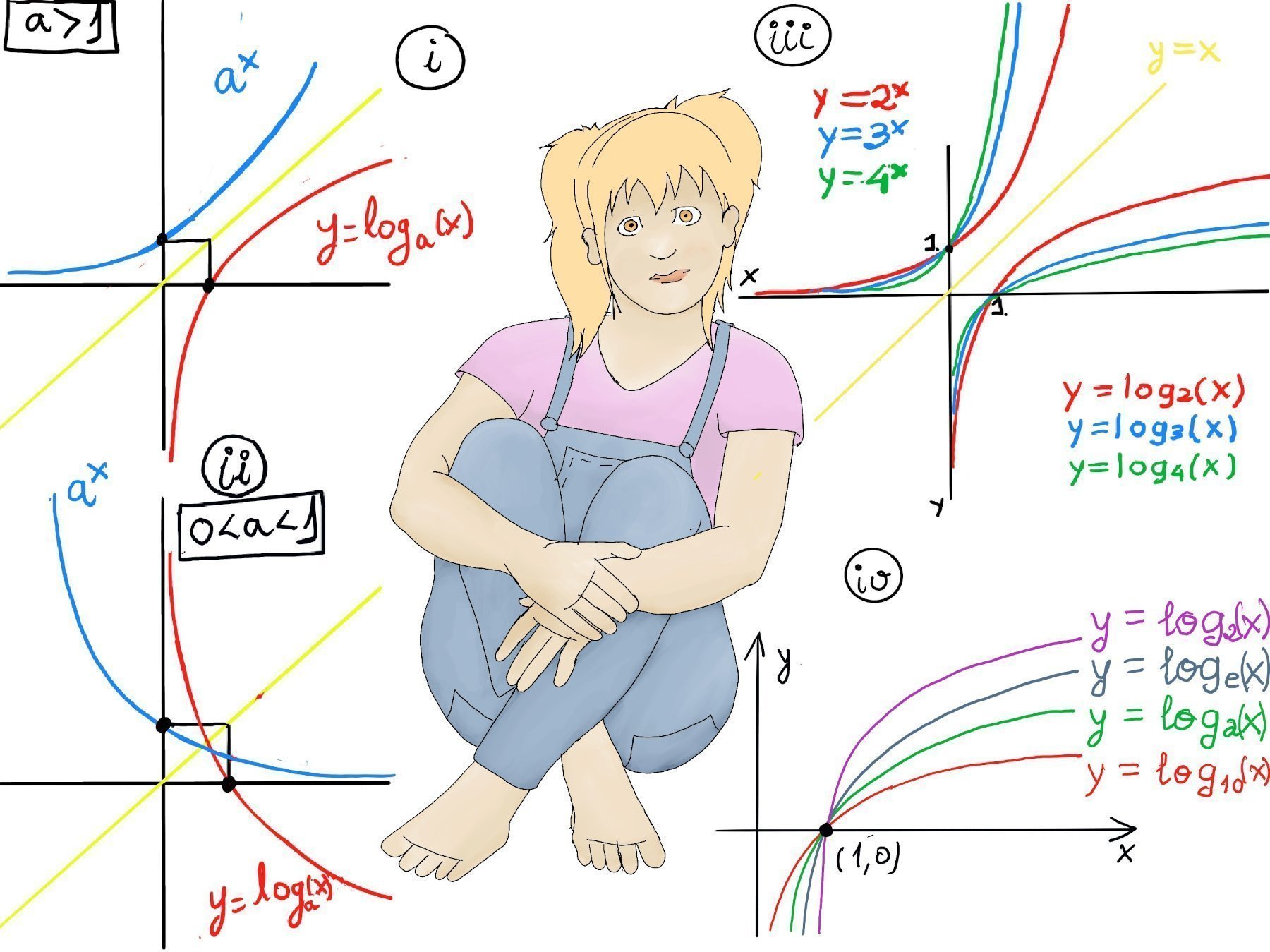

Examples are 2x, 7x, and (1⁄4)x. There are three kinds of exponential functions depending on whether a > 1, a = 1, or 0 < a < 1 -Figure 1.a.- The more important example is the natural exponential function, f(x) = ex where e is the Eulers Number, a mathematical constant approximately equal to 2.71828.

$\frac{d}{dx}e^x=e^x$ It’s the unique (up to scaling) function equal to its own derivative. $e=\lim _{n\rightarrow \infty }\left( 1+\frac{1}{n}\right) ^n$. Furthermore, $a^x=e^{x\ln (a)}$, so every exponential function is just a rescaled version of e^x.

It is important to realize that as x approaches negative infinity, the results become very small but never actually attain zero, e.g., 2-5 ≈ 0.03125, 2-15 ≈ 0.00003052. Besides, the base of an exponential function determines the rate of growth or decay. For a > 1, the larger the base, the faster the function grows (Figure iii).

Loosely speaking, the inverse function of a function f is a function that undoes the operation of the original function. If a function f maps each element x in its domain to a unique element y in its codomain, then the inverse function, denoted by $f^{-1}$, maps each such element y back to its corresponding x.

Formally, if f(x) = y, then $f^{-1}(y) = x$. This relationship can be summarized by the identities $f^{-1}(f(x)) = x, \forall x \in \mathrm{Dom}(f),$ and $f(f^{-1}(y)) = y, \forall y \in \mathrm{Dom}(f^{-1}).$

In mathematics, the logarithm is the inverse operation of exponentiation. We call the inverse of ax the logarithmic function with base a, that is, logax = y ↔ ay = x. In words, the logarithm of a number x to the base a, logax, is the exponent to which a must be raised to produce x, e.g., log4(64) = 3 because 43 = 64, log2(16) = 4 because 24 = 16, log8(512) = 3 because 83 = 512, but log2(-3) is undefined in the real numbers (logs require positive arguments).

The logarithm function is a fundamental mathematical tool that serves as the inverse of exponential growth, transforming multiplicative relationships into additive ones. Its applications span virtually every scientific discipline: in finance, logarithms calculate compound interest; in biology, they describe population dynamics and drug elimination from the body; in physics, they quantify radioactive decay and measure earthquake magnitudes. This remarkable versatility makes logarithms essential for solving real-world problems where quantities change at rates proportional to their current values.

Although the base of a logarithm can be any number, the most commonly used bases are 10 and e:

Let a > 0 with $a \neq 1$.

The bigger the logarithm base, the graph approaches the asymptote x = 0 quicker (Figure iii and iv).

Proof: Let $u = \log_a(x), v = \log_a(y)$. Then, $a^{u} = x, a^{v} = y.$ So $xy = a^{u}a^{v} = a^{u+v}$. Taking $\log_a$ gives $\log_a(xy) = u + v = \log_a(x)+\log_a(y)$.

Let y = logb(x) ↭ by = x and z = loga(x) ↭ az = x. Then, z = loga(x) = $log_a(b^y) = y·log_a(b) ⇒ log_b(x) = y = \frac{z}{log_a(b)} = \frac{log_a(x)}{log_a(b)}$

For x > 0, let y = ln(x) ⇒[By definition] ey = x ⇒[Differentiating both sides of this equation with respect to x. Recall (ex)’=ex] $\frac{d}{dx}(e^y) = \frac{d}{dx}(x) \implies[\text{Applying the chain rule}] e^y\frac{dy}{dx} = 1 \implies[\text{Sove for } \frac{dy}{dx}] \frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{e^y} = \frac{1}{x}.$ Thus, $\boxed{\frac{d}{dx}ln(x) = \frac{1}{x}}, \forall x \gt 0$

For x > 0, a > 0, and a ≠ 1, let y = loga(x) ⇒[By definition] ay = x ⇒ ln(ay) = ln(x) ⇒[Power Rule. loga(xn) = n·loga(x).] y·ln(a) = ln(x) ⇒ y = $\frac{ln(x)}{ln(a)}⇒$[1⁄ln(a) is a constant] $\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{ln(a)}\cdot \frac{1}{x} = \frac{1}{xln(a)}$. Thus, $\boxed{\frac{d}{dx}log_a(x) = \frac{1}{xln(a)}}, \forall x \gt 0$

For |u| < 1, we have the geometric series: $\frac{1}{1+u} = 1 - u + u^2 -u^3 \cdots$. This is just the usual geometric series applied with x = -u.

$ln(1+t) = \int_{0}^{t} \frac{du}{1+u}$. This follows from these statements:

Since the geometric series converges uniformly on |u| < 1, we are allowed to integrate term-by-term: $\int_{0}^{t}\frac{du}{1+u} = \int_{0}^{t} (1 - u + u^2 -u^3)du = t-\frac{t^2}{2}+\frac{t^3}{3}-\frac{t^4}{4}+\cdots$

The geometric series converges only for |u| < 1. Since the integration is done over the interval from 0 to t, we need the entire path to stay inside the disk |u| < 1. That requires: |t| < 1. The endpoint t = -1 is excluded because $\ln(1+t)$ has a singularity at t =-1. Thus, the radius of convergence is exactly 1.

Given $f(x) = \ln\left(\frac{x}{x+1}\right) = \ln(x) - \ln(x+1)$ The derivative using the properties of logarithms and the chain rule is: f’(x) = $\frac{1}{x}-\frac{1}{x+1} =[\text{Combining the fractions}] \frac{x+1}{x(x+1)} -\frac{x}{x(x+1)} = \frac{1}{x(x+1)}$

Solve $2^{3x-5}=7$. Take log base 2 of both sides to bring the exponent down: $3x-5=\log_2(7) \implies[\text{Isolate or solve for x by adding 5 and dividing by 3.}] x=\frac{\log_2(7) +5}{3}$.

Finding the Derivative of f(x) = $ln(\frac{x^2·sin(x)}{2x+1})$

Differentiate term by term using chain rule: f’(x) = $\frac{2}{x} + \frac{cos(x)}{sin(x)} -\frac{2}{2x+1} = \frac{2}{x} + cot(x) -\frac{2}{2x+1}$

y = xx ⇒[Take natural logarithm of both sides:] ln(y) = ln(xx) ⇒[Apply $ln(a^b) = b·ln(a)$:] ln(y) = xln(x)

Differentiate both sides (chain and product rule): $\frac{d}{dx} ln(y) = \frac{d}{dx} xln(x) ⇒ \frac{y'}{y} = ln(x)+1 ⇒[\text{Solve for y'}] y' = y(ln(x)+1) = x^x(ln(x)+1).$

Let’s convert $\log_2(9)$ to base e (natural logarithm), $log_2(9)=\frac{ln(9)}{ln(2)}$= [$ln(9) \approx 2.1972, ln(2) \approx 0.6931$] ≈ 3.1699 ≈ 3.17.

$log_3(81) =[\text{Using the change-of-base formula: }] \frac{log_{10}(81)}{log_{10}(3)}$ [Numerically, with common logarithms (base 10), $log_{10}(81) \approx 1.9082, log_{10}(3) \approx 0.4771$] $\approx \frac{1.9082}{0.4771} \approx 4 $.

Of course, since $81+3^4$, one also knows exactly that $log_3(81)=4$.

Simplify $log_8(\frac{1}{12})+log_8(\frac{12}{5})$

$log_8(\frac{1}{12})+log_8(\frac{12}{5})$ =[To simplify the given expression, we can use the product Rule which states that loga(xy) = loga(x) + loga(y)] $log_8(\frac{1}{12}·\frac{12}{5}) = log_8(\frac{1}{5}) = log_8(5^{-1})=-log_8(5).$

The solution to the equation $\ln(4x - 3) = 7$ is found by exponentiating both sides to eliminate the natural logarithm: ln(4x -3) = 7 ⇒ $e^{ln(4x-3)} = e^7 ⇒ 4x -3 = e^7 ⇒[\text{Solve for x}] x = \frac{e^7+3}{4}.$

To solve the equation $\log_4(x^2 - 2x) = \log_4(5x - 12)$, we can utilize the property of logarithms that states if $\log_a(b) = \log_a(c)$, then b = c provided a > 1 and b, c > 0.

log4(x2-2x) = log4(5x-12) ⇒[a = 4 > 1, logarithm is strictly increasing⇒ one-to-one] x2-2x = 5x-12 ⇒[Rearranging the equation gives us] x2 -7x + 12 = 0 ⇒[Next, we factor it] (x-3)(x-4) = 0 ⇒ x = 3 or 4.

It is crucial to check that these solutions do not result in taking the logarithm of a non-positive number. For x = 3, log4(32-2·3) = log4(3) = log4(5·3-12) and log4(42-2·4) = log4(8) = log4(5·4-12). Both solutions are valid since they do not lead to logarithms of zero or negative numbers.

$log_3(\sqrt{-7x+1})-7 = -4$⇒[Isolate the Logarithmic Term] $log_3(\sqrt{-7x+1}) = 3$⇒[Next, we convert the logarithmic equation to its exponential form:] $3^{log_3(\sqrt{-7x+1})}=3^3 = 27 \implies \sqrt{-7x+1} = 27$

Now, we square both sides to eliminate the square root: $-7x+1 = 27^2 = 729 ⇒[\text{Rearranging the equation gives:}] -7x = 729-1 = 728 ⇒[\text{Solve for x}] $x = \frac{-728}{7}$ = -104.

We need to check if this solution is valid by substituting x = −104 back into the original logarithmic expression: $log_3(\sqrt{-7·-104+1})-7 = -4↭log_3(\sqrt{729})-7 = -4 ↭ log_3(27)-7 = -4 ↭ 3-7 = -4$ and obviously $log_3(\sqrt{729})$ is a valid number ($\sqrt{729}$ is a positive real number, namely 27).

$log_3(2x+1)+log_3(x+8)=3$⇒[Using the product rule of logarithms, which states that loga(xy)=loga(x) + loga(y)] $log_3((2x+1)(x+8)) = 3 ⇒$[Next, we convert the logarithmic equation to its exponential form:] (2x+1)(x+8) = 33 = 27.

Expand and rearrange the equation, 2x2 +17x +8 = 27. It has two solutions x = -19⁄2, x = 1.

It is essential to make sure to plug these numbers into the original equation to ensure they do not result in taking the logarithm of a non-positive number.