|

|

|

An old joke that Adam told to Even, but makes cents, Once a man said to God “What’s a million years to you?”, and God said “A second.” So the man said to God “What’s a million dollars to you?”, and God said “A penny.” So the man said to God “Would you give me a penny?” And God replied, “Sure, just wait a second.”

Linear and quadratic approximations are methods used to approximate a complicated function with simpler, linear or quadratic functions near a specific point. This is useful when algebra becomes messy, the exact value is difficult to calculate, computationally costly, or tedious to find. These approximations are valuable in calculus and numerical analysis for estimating the behavior of functions near certain points, understanding local behaviour, or for simplifying calculations.

When using approximation, you sacrifice some accuracy for the ability to perform complex calculations easily and quickly.

Linear approximation does a very good job of approximating values of f(x) as long as we stay near x = a, that is, in the neighborhood around a. If a function y = f(x) is differentiable at a point (a, f(a)), the function looks like its tangent line in a small open interval containing a. It allows us to approximate the original function f (it is sometimes computationally too costly -in terms of resources- or algebraically complicated) with a simpler function L that is linear.

The tangent line provides the “best” linear approximation to f at the point a. In other words, zoom in far enough on a smooth curve at x = a, and it becomes indistinguishable from a straight line: the tangent.

For a function f differentiable at $x_0$, the linear approximation of $f$ at $x_0$ is the tangent line: $\boxed{L(x) = f(x_0) + f'(x_0)(x - x_0)}$ (it touches the curve at this particular point $x_0$).

Approximation: $f(x) \approx L(x) \quad \text{for } x \approx x_0$ (for x near $x_0$). This is the first-order Taylor polynomial of $f$ at $x_0$. The closer $x$ is to $x_0$, the better the approximation is (error is generally of order $(x - x_0)^2$).

We know $\ln(1) = 0, (\ln x)' = \dfrac{1}{x}$, so $\ln'(1) = 1$. Thus, the linear approximation at $x_0 = 1$ is: $L(x) = \ln(1) + \ln'(1)(x - 1) = 0 + 1(x - 1) = x - 1.$

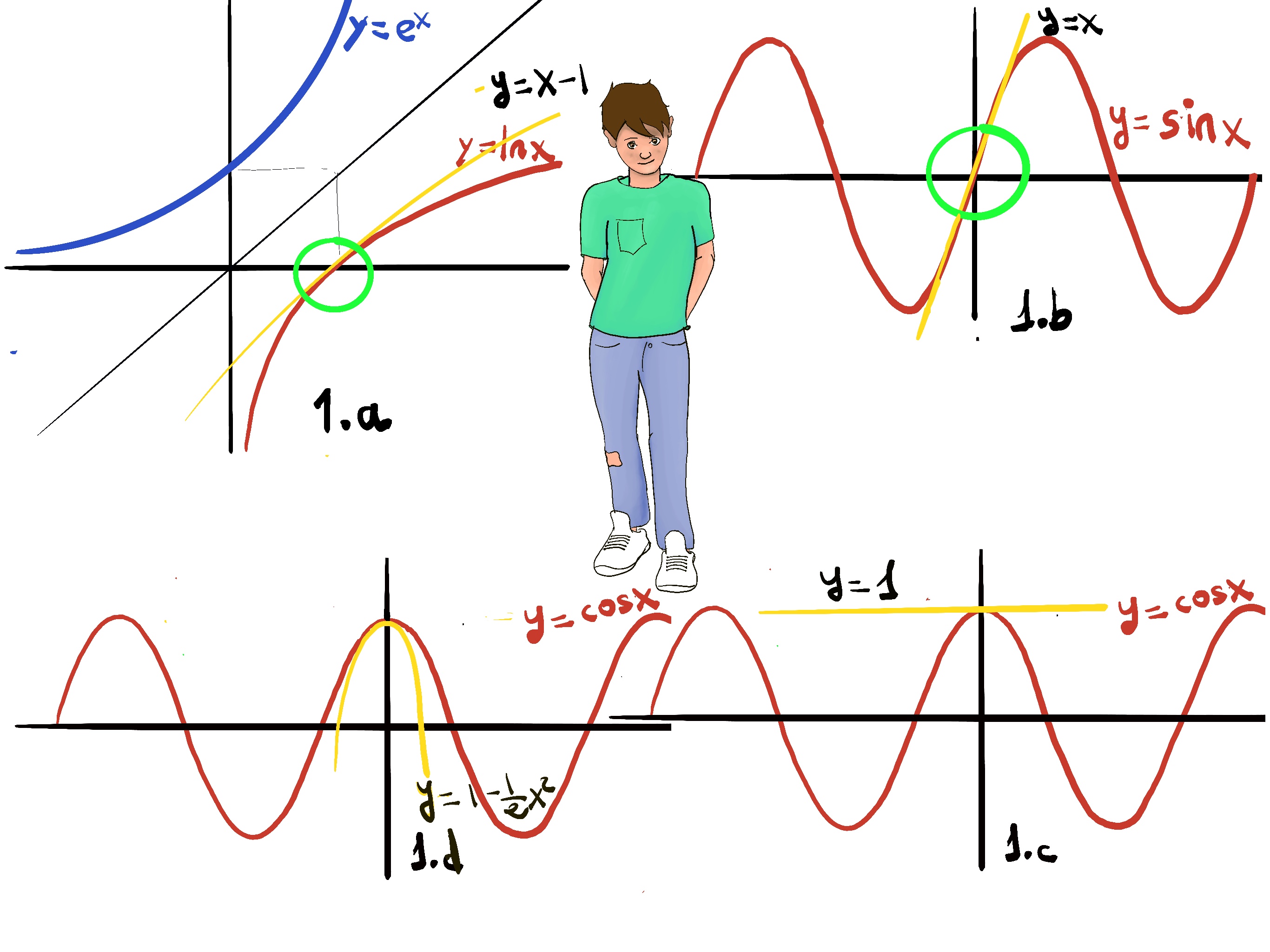

So for $x$ near 1: $\ln x \approx x - 1.$ (Figure 1.a).

Essential Approximation (it is a good idea to memorize these): $\sin x \approx x$, $\cos x \approx 1$, $\tan x \approx x$, $e^x \approx 1 + x$, $\ln(1 + x) \approx x$, $(1 + x)^r \approx 1 + rx$, $\frac{1}{1 + x} \approx 1 - x$, $\frac{1}{1 - x} \approx 1 + x$, $\sqrt{1 + x} \approx 1 + \frac{x}{2}$, $\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + x}} \approx 1 - \frac{x}{2}$.

Special cases: r = 2, $(1+x)^2 \approx 1 + 2x$; r = 3, $(1+x)^3 \approx 1 + 3x$; $r = \frac{1}{2}$, $\sqrt{1+x} \approx 1 + \frac{x}{2}$; r = -1, $\frac{1}{1+x} \approx 1 - x$; $r = -\frac{1}{2}$, $\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+x}} \approx 1 - \frac{x}{2}$.

Example: $(1.1)^3 = 1.331 \approx 1 + 3(0.1) = 1.3$

Let $f(x) = \sqrt[4]{x} = x^{1/4}$. Choose $x_0 = 1$ (near 1.1 and easy to compute).

$1^{1/4} = 1, f'(x) = \frac{1}{4}x^{-3/4}, f'(1) = \frac{1}{4}$. Linear approximation: $L(x) = 1 + \frac{1}{4}(x - 1)$

Evaluate at $x = 1.1$: $\sqrt[4]{1.1} \approx 1 + \frac{1}{4}(0.1) = 1.025$

Actual value: $\sqrt[4]{1.1} = 1.02411...$ Error: $|1.025 - 1.02411| \approx 0.00089$ (less than 0.1%)

Let $f(x) = \sqrt{x}$. Choose $x_0 = 4$ (perfect square near 4.1).

Calculations: $\sqrt{4} = 2, f'(x) = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{x}}, f'(4) = \frac{1}{4}$.

Linear approximation: $L(x) = 2 + \frac{1}{4}(x - 4)$

Evaluate at $x = 4.1$: $\sqrt{4.1} \approx 2 + \frac{1}{4}(0.1) = 2.025 \approx[\text{Actual value}] 2.02485...$

Individual approximations: $e^{-3x} \approx 1 + (-3x) = 1 - 3x, (1+x)^{-1/2} \approx 1 + \left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)x = 1 - \frac{x}{2}$

Combine both individual approximations: $\frac{e^{-3x}}{\sqrt{1+x}} = e^{-3x}(1+x)^{-1/2} \approx (1 - 3x)\left(1 - \frac{x}{2}\right) =[\text{Expand (keeping only linear terms)}]= 1 - \frac{x}{2} - 3x + \frac{3x^2}{2} \approx 1 - \frac{7x}{2}$

We ignore $x^2$ terms (quadratic and higher other terms) since they’re negligible for small $x$.

$\boxed{\frac{e^{-3x}}{\sqrt{1+x}} \approx 1 - \frac{7x}{2}}$

$\frac{e^{-3x}}{\sqrt{1+x}} = e^{-3x}(1+x)^{-1/2} ≅ (1-3x)(1-\frac{1}{2}x) ≅~ 1 -3x -\frac{1}{2}x +\frac{3}{2}x^{2} ≅ 1 -3x -\frac{1}{2}x ≅ 1 -\frac{7}{2}x$. Observe that we do not care about quadratic and higher other terms and consider them as negligible as long as we are close enough to 0.

The linear approximation helps evaluate certain limits intuitively, e.g., $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\sin x}{x}$

Since $\sin x \approx x$ for $x$ near 0: $\frac{\sin x}{x} \approx \frac{x}{x} = 1$

This suggests (and is consistent with) $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\sin x}{x} = 1$.

| Limit | Approximation | Result |

|---|---|---|

| $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{e^x - 1}{x}$ | $\frac{(1+x) - 1}{x} = 1$ | $1$ |

| $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\ln(1+x)}{x}$ | $\frac{x}{x} = 1$ | $1$ |

| $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1 - \cos x}{x}$ | $\frac{1 - 1}{x} = 0$ | $0$ |

| $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\tan x}{x}$ | $\frac{x}{x} = 1$ | $1$ |

When using approximation you sacrifice some accuracy for the ability to perform complex calculations easily and fast. Quadratic approximation is used when the linear approximation is not good or close enough, e.g., the linear approximation of $\cos(x)$ near 0 is $L(x) = 1$ — a horizontal line! This doesn’t capture the parabolic shape of cosine at all.

For a function $f$ that is twice differentiable at $x_0$, the basic formula for quadratic approximation at $x_0$ is $\boxed{Q(x) = f(x_0) + f'(x_0)(x - x_0) + \frac{f''(x_0)}{2}(x - x_0)^2}$

This provides the best-fit parabola to the function at $x_0$ and this is generally enough for $x \approx x_0$.

Ideally, the quadratic approximation of a quadratic function, say $f(x) = a + bx + cx^2$, should be identical to the original function.

At $x_0 = 0$: (i) $f(0) = a$; (ii) $f'(x) = b + 2cx \Rightarrow f'(0) = b$; (iii) $f''(x) = 2c \Rightarrow f''(0) = 2c$.

Solving: $f(0) = a, f'(0) = b, f''(0) = 2c \implies c = \frac{f''(0)}{2}$. So: $f(x) = f(0) + f'(0)x + \frac{f''(0)}{2}x^2$ ✓

The linear approximation of cos(x) near 0 is the straight horizontal line y = 1. This doesn’t seem like a very good approximation. The quadratic approximation to the graph of cos(x) is a parabola that opens downward: $\cos(x) \approx 1 - \frac{x^2}{2}$ (1.d.), this is much closer to the shape of cos(x) than the line y = 1.

$f(x) = \cos x$; $x_0 = 0, \cos 0 = 1, f'(x) = -\sin x, f'(0) = 0, f''(x) = -\cos x, f''(0) = -1$

Quadratic approximation: $Q(x) = 1 + 0 \cdot x + \frac{-1}{2}x^2 = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2}$.

$\cos(0.5) =[\text{Real value}] 0.87758...$ vs. $1 - \frac{0.25}{2} = 0.875$.

$f(x) = e^x; x_0 = 0; f(0) = 1, f'(0) = 1, f''(0)= 1$.

Quadratic approximation: $Q(x) = 1 + x + \frac{1}{2}x^2$

$e^{0.5} =[\text{Real value}] 1.6487...$ vs. $1 + 0.5 + 0.125 = 1.625$

$f(x) = \ln(1 + x); x_0 = 0; f(0) = 0, f'(x) = \frac{1}{1+x}, f'(0) = 1, f''(x) = -\frac{1}{(1+x)^2}, f''(0) = -1$

Quadratic approximation: $Q(x) = 0 + x + \frac{-1}{2}x^2 = x - \frac{x^2}{2}$

Let $x = 0.1, \ln(1.1) =[\text{Actual value}] 0.09531... \ln(1 + 0.1) \approx 0.1 - \frac{0.01}{2} = 0.095$

$f(x) = (1 + x)^r$, $x_0 = 0; f(0) = 1, f'(x) = r(1+x)^{r-1}, f'(0) = r, f''(x) = r(r-1)(1+x)^{r-2}, f''(0) = r(r-1)$.

Quadratic approximation: $Q(x) = 1 + rx + \frac{r(r-1)}{2}x^2$.

Special case: $r = \frac{1}{2}$ (square root) $\sqrt{1+x} \approx 1 + \frac{x}{2} + \frac{\frac{1}{2}(-\frac{1}{2})}{2}x^2 = 1 + \frac{x}{2} - \frac{x^2}{8}$

f(4) = 2, f’(x) = $\frac{1}{2\sqrt{x}} = \frac{1}{2}·x^{\frac{-1}{2}}, f'(4) = \frac{1}{4}$; f’’(x)= $\frac{1}{2}·\frac{-1}{2}·x^{\frac{-1}{2}-1} = \frac{-1}{4·x^{\frac{3}{2}}} = \frac{-1}{4·x·\sqrt{x}}, f''(4) = -\frac{1}{32}$, then

Expanding: $Q(x) = 2 + \frac{x}{4} - 1 - \frac{1}{64}(x^2 - 8x + 16) = 1 + \frac{x}{4} - \frac{x^2}{64} + \frac{x}{8} - \frac{1}{4} = \frac{3}{4} + \frac{3x}{8} - \frac{x^2}{64}$.

$\sqrt{5} =[\text{Actual value}] = 2.2360679... \approx[\text{Linear}] 2.25 \text{ (error ≈ 0.01393) } \approx[\text{Quadratic}] 2.2344...$ (error ≈ 0.00169). The quadratic approximation is indeed much closer because it captures the concavity of the square root function.

$x_0 = 1$. Calculate derivatives: $f(x) = xe^{-2x}, f(1) = 1 \cdot e^{-2} = e^{-2}, f'(x) = e^{-2x} + x(-2e^{-2x}) = e^{-2x}(1 - 2x), f'(1) = e^{-2}(1 - 2) = -e^{-2}$.

$f''(x) = -2e^{-2x}(1-2x) + e^{-2x}(-2) = -2e^{-2x}(1-2x+1) = -4e^{-2x}(1-x), f''(1) = -4e^{-2}(0) = 0$

Quadratic approximation: $Q(x) = e^{-2} + (-e^{-2})(x-1) + \frac{0}{2}(x-1)^2 = e^{-2}(1 - (x-1)) = e^{-2}(2 - x)$

Since $f''(1) = 0$, the quadratic approximation equals the linear approximation!

Individual approximations: $e^{-3x} \approx 1 + (-3x) + \frac{(-3)^2}{2}x^2 = 1 - 3x + \frac{9x^2}{2}$; $(1+x)^{-1/2} \approx 1 + \left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)x + \frac{(-\frac{1}{2})(-\frac{3}{2})}{2}x^2 = 1 - \frac{x}{2} + \frac{3x^2}{8}$

Multiply (keeping terms up to $x^2$): $\left(1 - 3x + \frac{9x^2}{2}\right)\left(1 - \frac{x}{2} + \frac{3x^2}{8}\right)$

Expand systematically:

Result: $\boxed{\frac{e^{-3x}}{\sqrt{1+x}} \approx 1 - \frac{7x}{2} + \frac{51x^2}{8}}$

The Taylor series of a function f(x) about a point $x_0$ is given by $f(x) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{f^{(n)}(x_0)}{n!}(x - x_0)^n$ provided the function is infinitely differentiable at $x_0$ and the series converges to f(x) in some neighborhood of $x_0$. Truncating the series after a finite number of terms yields a polynomial approximation of f.

| Terms | Name | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| First 1 | Constant | $f(x_0)$ |

| First 2 | Linear | $f(x_0) + f'(x_0)(x-x_0)$ |

| First 3 | Quadratic | $f(x_0) + f'(x_0)(x-x_0) + \frac{f''(x_0)}{2}(x-x_0)^2$ |

| First 4 | Cubic | $f(x_0) + f'(x_0)(x-x_0) + \frac{f''(x_0)}{2}(x-x_0)^2 + \frac{f'''(x_0)}{6}(x-x_0)^3$ |

| All | Taylor Series | $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{f^{(n)}(x_0)}{n!}(x - x_0)^n$ |

| $x$ | $e^x$ | $L(x) = 1+x$ | $Q(x) = 1+x+\frac{x^2}{2}$ | Error L(x) | Error Q(x) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| 0.1 | 1.1052 | 1.1 | 1.105 | 0.0052 (0.47%) | 0.0002 (0.02%) |

| 0.5 | 1.6487 | 1.5 | 1.625 | 0.1487 (9.02%) | 0.0237 (1.44%) |

| 1 | 2.7183 | 2 | 2.5 | 0.7183 (26.43%) | 0.2183 (8.03%) |

The quadratic approximation Q(x) is significantly closer to $e^x$ than the linear L(x), as the $x^2$ term captures the curvature near x = 0.

| Function | Series | Radius of Convergence | Key Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| $e^x$ | $\displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{x^n}{n!} = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^3}{3!} + \cdots$ | $\mathbb{R}$ (all $x$) | All terms positive; rapid growth |

| $\sin x$ | $\displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n x^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!} = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \cdots$ | $\mathbb{R}$ | Odd powers only; alternating signs |

| $\cos x$ | $\displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n x^{2n}}{(2n)!} = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \cdots$ | $\mathbb{R}$ | Even powers only; alternating signs |

| $\ln(1+x)$ | $\displaystyle\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^{n+1} x^n}{n} = x - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^3}{3} - \cdots$ | $(-1, 1]$ | Slow convergence; $x=1$ gives $\ln 2 = 1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \cdots$ |

| $(1+x)^r$ | $\displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^\infty \binom{r}{n} x^n = 1 + rx + \frac{r(r-1)}{2!}x^2 + \cdots$ | $\vert x\vert < 1$ | Binomial series; terminates if $r \in \mathbb{N}$ |

| $\frac{1}{1-x}$ | $\displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^\infty x^n = 1 + x + x^2 + x^3 + \cdots$ | $\vert x \vert < 1$ | Geometric series; divergence at $\vert x \vert \geq 1$ |

$\ln (1+x)=\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }\frac{(-1)^{n+1}x^n}{n}=x-\frac{x^2}{2}+\frac{x^3}{3}-\cdots $. Interval of convergence: $-1 \lt x \leq 1$. At x = 1: converges to $\ln(2)$. At x = -1: $\sum (-1)^{n+1}(-1)^n/n = -\sum 1/n$ diverges. Alternating, slowly convergent near x = 1; great for theoretical work, not for fast computations.

For a function f with n+1 continuous derivatives near $x_0$, the Taylor polynomial of degree n satisfies: $f(x)=T_n(x)+R_n(x)$ where the remainder has the form $R_n(x)=\frac{f^{(n+1)}(\xi)}{(n+1)!}(x-x_0)^{n+1}$ for some $\xi$ between x and $x_0$.

Taking absolute values and bounding the derivative gives: $|R_n(x)|\leq \frac{M_{n+1}}{(n+1)!}|x-x_0|^{n+1}$, where $M_{n+1}=\max_{t\mathrm{\ between\ }x\mathrm{\ and\ }x_0}|f^{(n+1)}(t)|$.

Linear approximation: (n = 1) Taylor polynomial: $L(x)=f(x_0)+f'(x_0)(x-x_0)$. Linear approximation error: $|f(x)-L(x)|\leq \frac{M_2}{2}|x-x_0|^2$ where $M_2 = \max|f''(t)|$ for $t$ between $x$ and $x_0$.

Quadratic approximation (n = 2): Taylor polynomial: $Q(x)=f(x_0)+f'(x_0)(x-x_0)+\frac{f''(x_0)}{2}(x-x_0)^2.$ Quadratic approximation error: $|f(x)-Q(x)|\leq \frac{M_3}{6}|x-x_0|^3$ where $M_3 = \max|f'''(t)|$ for $t$ between $x$ and $x_0$.

They tell us: