|

|

|

The best number is 73. Why? 73 is the 21st prime number. Its mirror, 37, is the 12th and its mirror, 21, is the product of multiplying 7 and 3… and in binary 73 is a palindrome, 1001001, which backwards is 1001001, the Big Bang Theory.

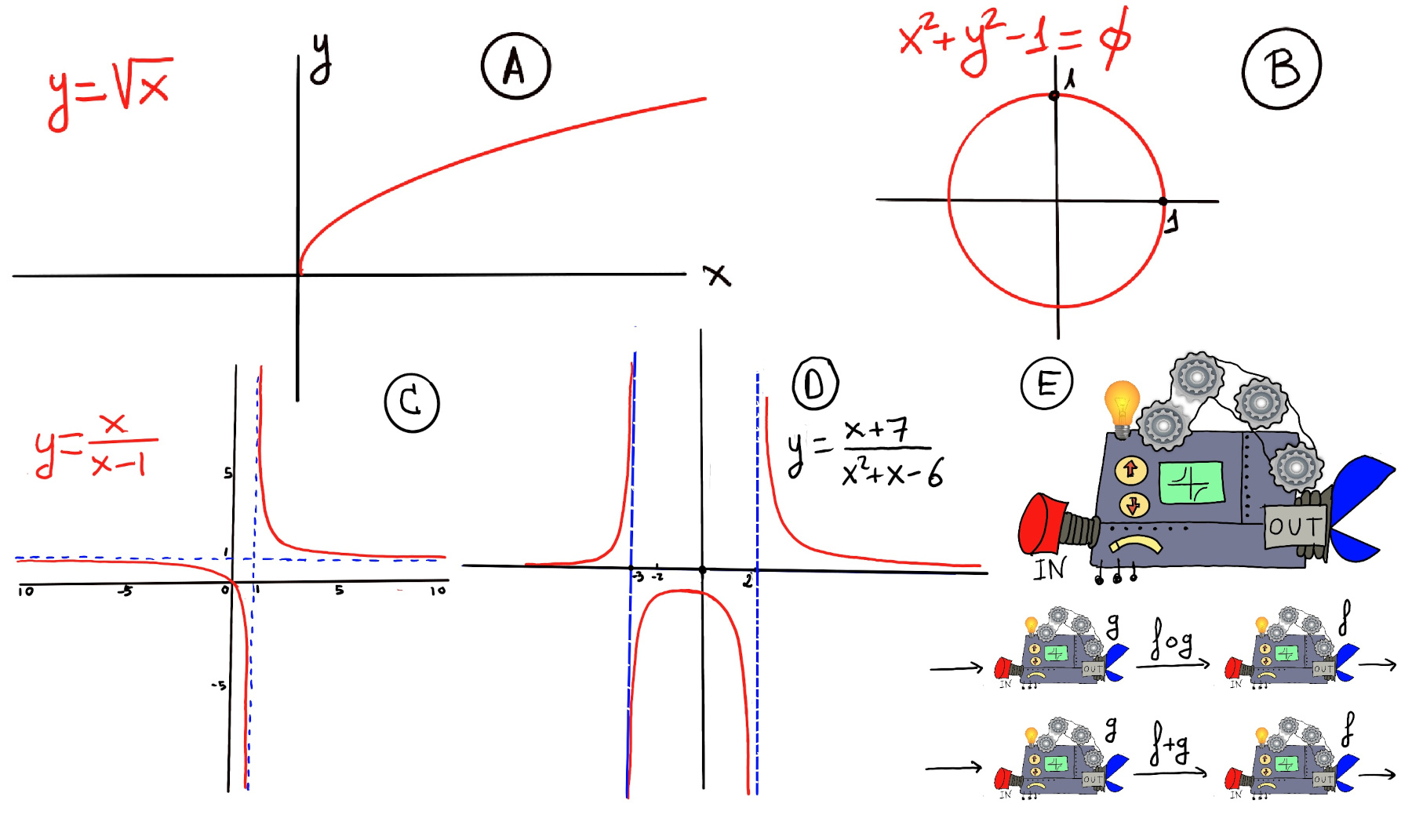

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range). A mathematical function is like a black box that takes certain input values and generates corresponding output values (Figure E).

Very loosing speaking, a limit is the value to which a mathematical function gets closer and closer to as the input gets closer and closer to some given value.

A limit describe what is happening around a given point, say “a”. It is the value that the function approaches as the input approaches “a”, and it does not depend on the actual value of the function at a, or even on whether the function is defined at “a” at all.

Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis and the understanding of how functions behave. The concept of a limit can be written or expressed as $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L.$ This notation is read as “the limit of f as x approaches a equals L”.

Intuitively, this means that the values of f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L (and I mean as close as we like, e.g., L ± 0.1, L ± 0.01, L ± 0.001, and so on), by choosing values of x sufficiently close to a, but not necessarily equal to a.

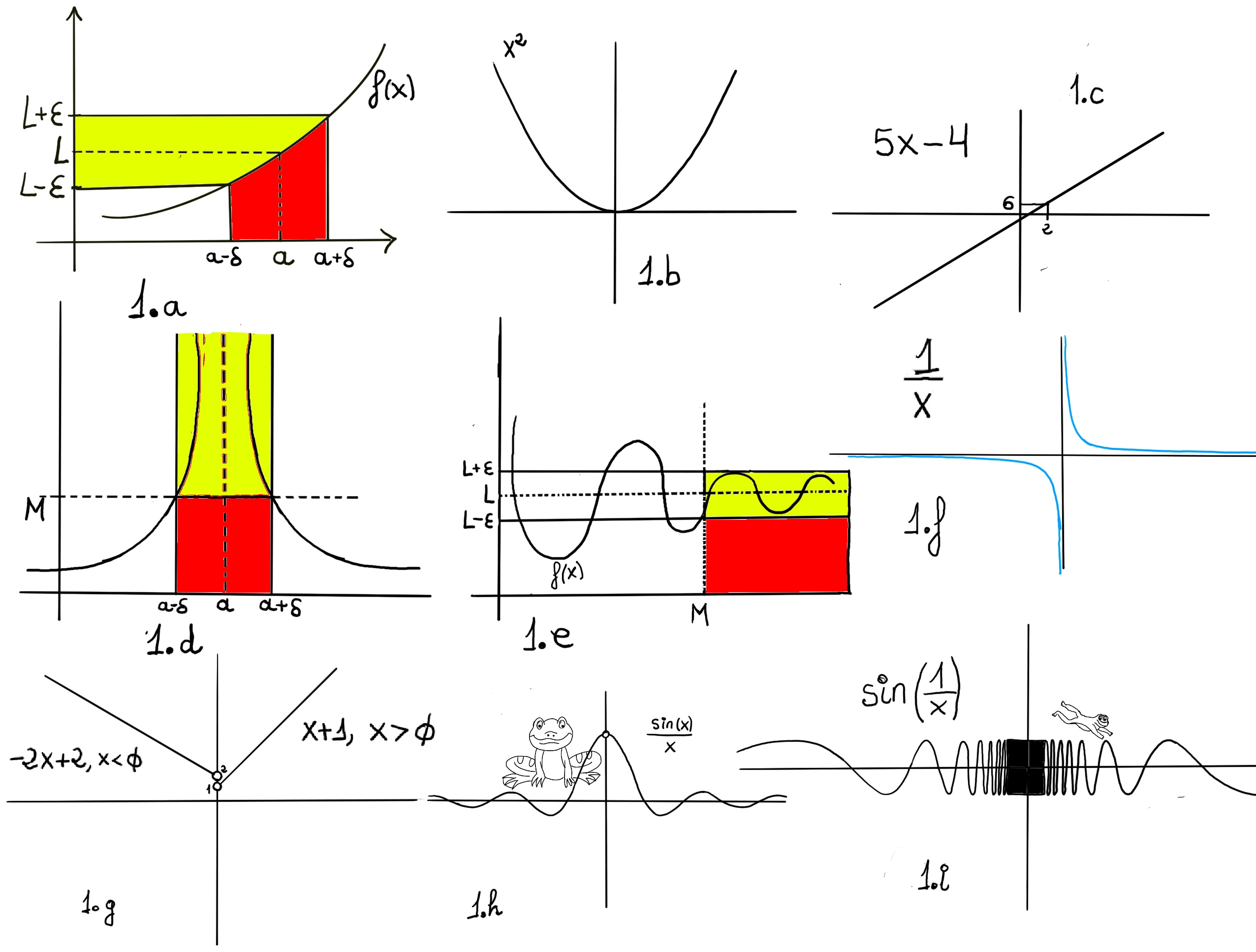

Formal definition. We say that the limit of f, as x approaches a, is L, and write $\lim_{x \to a}f(x) = L$. For every real ε > 0, there exists a real δ > 0 such that whenever 0 < | x − a | < δ we have | f(x) − L | < ε. In other words, we can make f(x) arbitrarily close to L, f(x)∈ (L-ε, L+ε) (within any distance ε > 0) by making x sufficiently close to a (within some distance δ > 0, but not equal to a) (x ∈ (a-δ, a+δ), x ≠ a) -Fig 1.a.-

Limits at infinity are used to describe the long-term behavior of functions as the independent variable grows without bound in the positive or negative direction, that is, as $x \to \infty$ or $x \to -\infty$.

In simple terms, they answer the question: What happens to the values of the function when x becomes very large (or very negative)? Or, more philosophically, what occurs when everything spirals completely out of control —as stupidity in this chaotic and crazy world approaches infinity.😄.

Definition. Let f(x) be a function defined on an interval (K, ∞) for some real number K. We say that $\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L$ if and only if $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists M>0: \text{ such that } |f(x)-L|<\epsilon, whenever~ x>M.$ In this case, the line y = L is called a horizontal asymptote of the graph of f. We can make f(x) as close as we want to L by making x large enough, -Figure 1.e.-

Definition. Let f(x) be a function defined on an interval (-∞, K) for some real number K. We say that $\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L$ if and only if $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists M<0: \text{ such that } |f(x)-L|<\epsilon, whenever~ x < M$ We can make f(x) as close as we want to L by making x small enough (very negative).

As $x \to \infty$, different types of functions grow at vastly different rates. Understanding this hierarchy is essential for comparing long-term behavior, evaluating limits, and analyzing algorithmic complexity.

From slowest-growing to fastest-growing as $x \to \infty$: (a > 0, b > 1, c > 1) Constants (parked car) ≪ $log_b(x) \text{ (Logarithmic -bicycle-) } ≪ x^a \text{ (Polynomial -car-, a=any positive power) } ≪ b^x \text{ (Exponential -rocket-, base b > 1) } ≪ x! \equiv x^x$ (Factorials and $x^x$ -hyperdrive-) where “≪” means “grows asymptotically much slower than”.

Examples: $\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{ln(x)}{x^a} = 0$ (logarithms lose to polynomials; Any positive power of x, no matter how small, eventually outgrows any logarithm), $\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{x^a}{b^x} = 0$ (Exponential growth (with base > 1) always dominates polynomial growth), $\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{b^x}{x^x} = 0, \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{b^x}{x!} = 0$ (Factorial and $x^x$ growth outpace even exponential growth).

For comparing logarithms and polynomials: $\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{ln(x)}{x^a} =[\text{L'Hôpital's Rule}] \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\frac{1}{x}}{ax^{a-1}} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{ax^a}=0$

For comparing polynomials and exponentials, multiple applications of L’Hôpital’s Rule show that differentiating a polynomial eventually yields a constant, while differentiating an exponential yields another exponential.

For rational functions, only the highest-degree terms matter, $\lim_{x \to \pm\infty}\frac{a_nx^n + \cdots + a_0}{b_mx^m + \cdots + b_0}$

Technique: Divide by Highest Power in Denominator, $\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{3x^2 - 2x + 1}{5x^2 + 4} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{3 - \frac{2}{x} + \frac{1}{x^2}}{5 + \frac{4}{x^2}} = \frac{3 - 0 + 0}{5 + 0} = \frac{3}{5}$

If $\lim_{x \to \infty} \dfrac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ yields $\dfrac{\infty}{\infty}$ or $\dfrac{0}{0}$: $\boxed{\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}}$

Example: $\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{x^2}{e^x} =[\text{Type: } \infty/\infty] \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{2x}{e^x} =[\text{Type: } \infty/\infty] \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{2}{e^x} = 0$

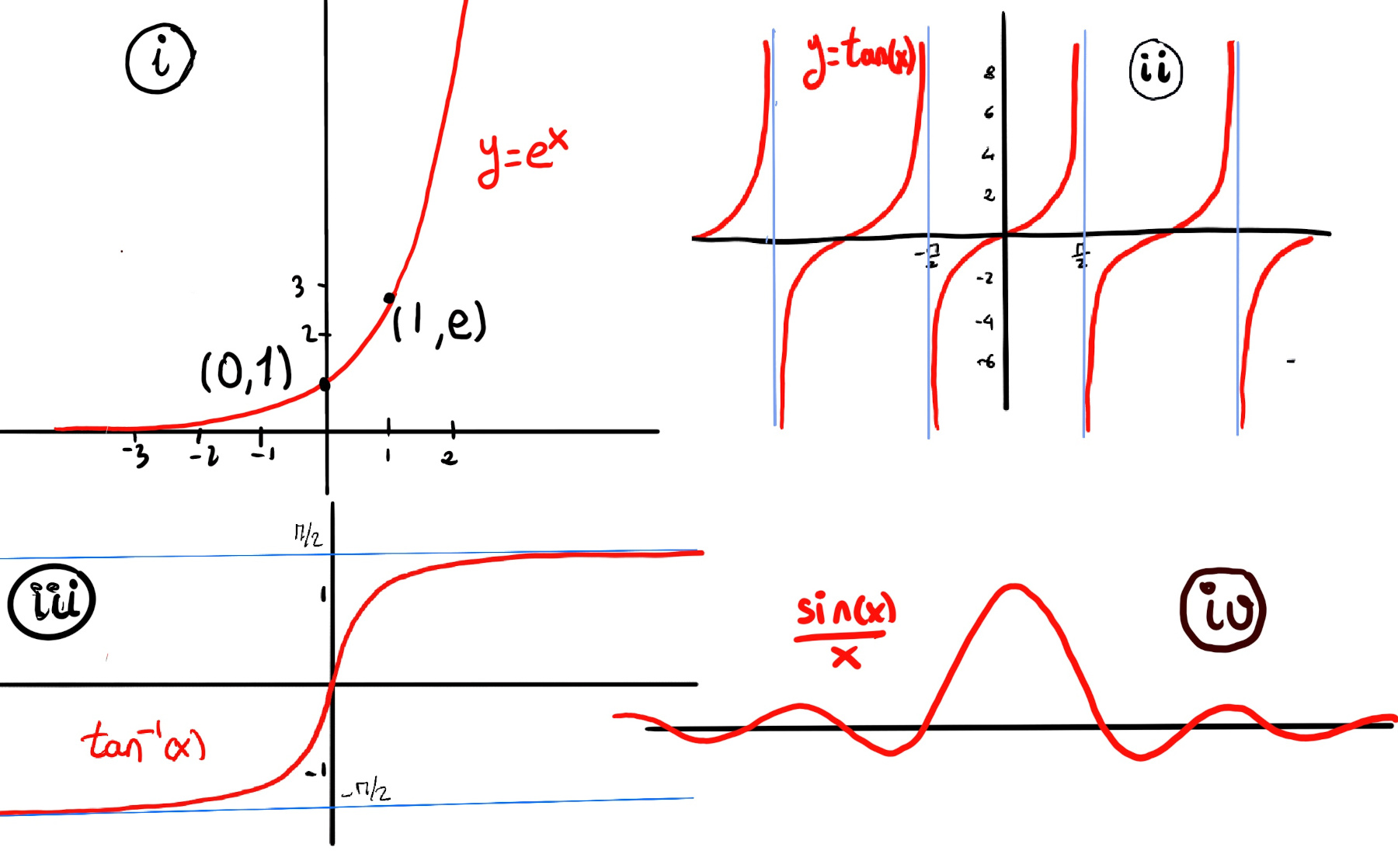

| Function | $\lim_{x \to \infty}$ | $\lim_{x \to -\infty}$ | Horizontal Asymptote(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\dfrac{1}{x}$ | $0$ | $0$ | $y = 0$ |

| $e^x$ | $\infty$ | $0$ | $y = 0$ (left only) |

| $e^{-x}$ | $0$ | $\infty$ | $y = 0$ (right only) |

| $\arctan(x)$ | $\dfrac{\pi}{2}$ | $-\dfrac{\pi}{2}$ | $y = \pm\dfrac{\pi}{2}$ |

| $\tanh(x)$ | $1$ | $-1$ | $y = \pm 1$ |

| $\dfrac{1}{1+e^{-x}}$ | $1$ | $0$ | $y = 0, y = 1$ |

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists M>0: |\frac{1}{x}|<\epsilon, whenever~ x>M$

This inequality is equivalent to $\frac{1}{x} \lt \epsilon \iff x \gt \frac{1}{\epsilon}$ (x is always positive).

Let’s choose $\boxed{M = \frac{1}{\epsilon}}, x>\frac{1}{\epsilon}$. Then, for all x > M, $|x|>\frac{1}{\epsilon} ⇨ \epsilon>\frac{1}{|x|} ⇒ |\frac{1}{x}| < ε$∎

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists M>0: |\frac{1}{x-3}-0|<\epsilon, whenever~ x > M$

x > M ⇒ x-3 > M -3 ⇒[Consider x-3 > M -3 >0 because M is as bigger as we want, they are both positive] $|\frac{1}{x-3}| = \frac{1}{x-3}<\frac{1}{M-3}$ =[This is our objective] ε ⇒ $\boxed{M = \frac{1}{ε} + 3}$.

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists M<0, M = \frac{1}{ε} + 3: |\frac{1}{x-3}|<\epsilon, whenever~ x > M$ because $|\frac{1}{x-3}|<\frac{1}{M-3} = \frac{1}{\frac{1}{ε} + 3-3} = ε$∎

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists M>0: |\frac{3x}{2x+1} - \frac{3}{2}|<\epsilon, whenever~ x > M$

$|\frac{3x}{2x+1} - \frac{3}{2}| = |\frac{6x-6x-3}{2(2x+1)}|=\frac{3}{2|2x+1|} =$[Here’s the key🔑 idea, x > M > 0, everything is positive] $\frac{3}{2(2x+1)} < \frac{3}{2(2x)} = \frac{3}{4x} < \frac{1}{x} < \frac{1}{M}$ [Let’s choose $\boxed{M= \frac{1}{\varepsilon}}$] $\frac{1}{\frac{1}{ε}} = ε$ ∎

$\forall N>0, \exists M>0: \sqrt{3x+1}>N, whenever~ x > M$

$\sqrt{3x+1}>$ [x > M > 0 and sqrt is a strictly increasing function] $\sqrt{3x}$ >[$\sqrt{3}>1$] $\sqrt{x}$> [x > M] $\sqrt{M}$ [Choose M = N2] = N ∎

$\forall \epsilon>0, \exists M>0: |\frac{1}{x^2}-0|<\epsilon, whenever~ x > M$

$|\frac{1}{x^2} -0| = \frac{1}{x^2} < \frac{1}{M^2}$ [Let’s choose $\frac{1}{M^2}=ε↭ \boxed{M = \frac{1}{\sqrt{ε}}}$] = ε ∎

$\forall N>0, \exists M>0: \sqrt{x-3}>N, whenever~ x > M$

$\sqrt{x-3} > \sqrt{M-3}$ [Select M such that $\sqrt{M-3}=N ↭ N^2 = M-3↭ \boxed{M = N^2+3}$] = N∎