|

|

|

To be a star, you must shine your own light, follow your path, and don’t worry about the darkness, for that is when the stars shine brightest. Always do what you are afraid to do, Ralph Waldo.

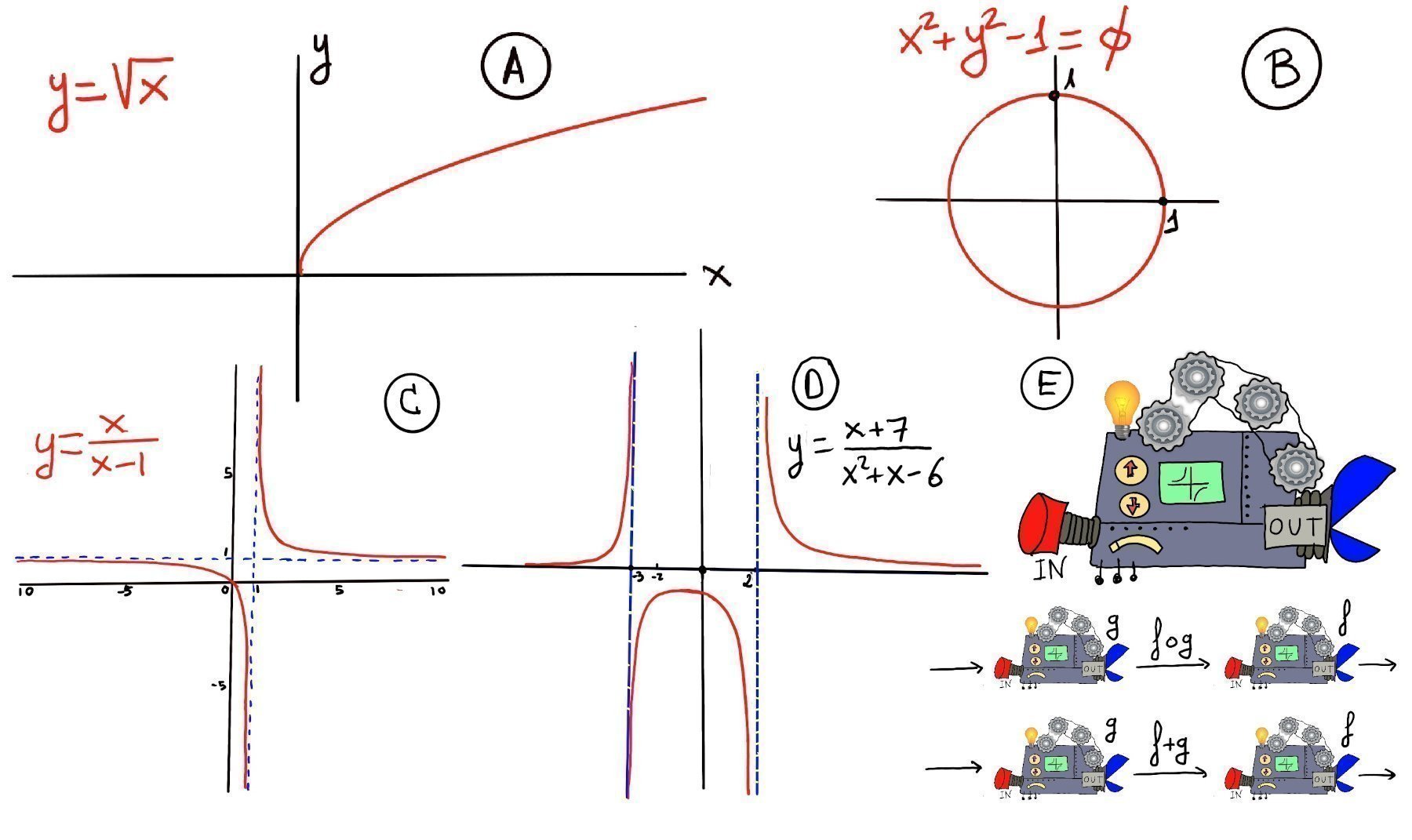

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ. A mathematical function can be thought of as a black box (or machine) that takes an input from its domain and produces exactly one output in its codomain. Inside the machine lives a specific rule (formula, procedure, or mapping) that dictates or tells you which output corresponds to each input, and a key property is uniqueness —each input maps to a single, deterministic output. No input can ever produce two different results (Figure E). The function f(x) = x2 accepts any real number x (domain: ℝ) and returns exactly one non-negative value x2 (output in codomain: [0,∞)). The input 3 always yields 9, never any other value.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$.💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

First Derivative Test. Let f be differentiable on an open interval containing c, except possibly at c itself, and let c be a critical point (so f′(c) = 0 or f′ is undefined). Then:

Very loosing speaking, a limit is the value to which a mathematical function gets closer and closer to as the input gets closer and closer to some given value.

A limit describe what is happening around a given point, say “a”. It is the value that the function approaches as the input approaches “a”, and it does not depend on the actual value of the function at a, or even on whether the function is defined at “a” at all.

Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis and the understanding of how functions behave. The concept of a limit can be written or expressed as $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L.$ This notation is read as “the limit of f as x approaches a equals L”.

Intuitively, this means that the values of f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L (and I mean as close as we like, e.g., L ± 0.1, L ± 0.01, L ± 0.001, and so on), by choosing values of x sufficiently close to a, but not necessarily equal to a.

Consider the function f(x) = 2x2 - 3x + 1. To compute or calculate $\lim_{x \to 2} 2x^2 -3x +1$, we observe that f is a polynomial, hence continuous. Therefore, the limit of f as x approaches 2 equals the value of the function at x = 2: $\lim_{x \to 2}(2x^2 -3x +1) = 2^2 -3\cdot 2 + 1 = 8 - 6 +1 = 3$.

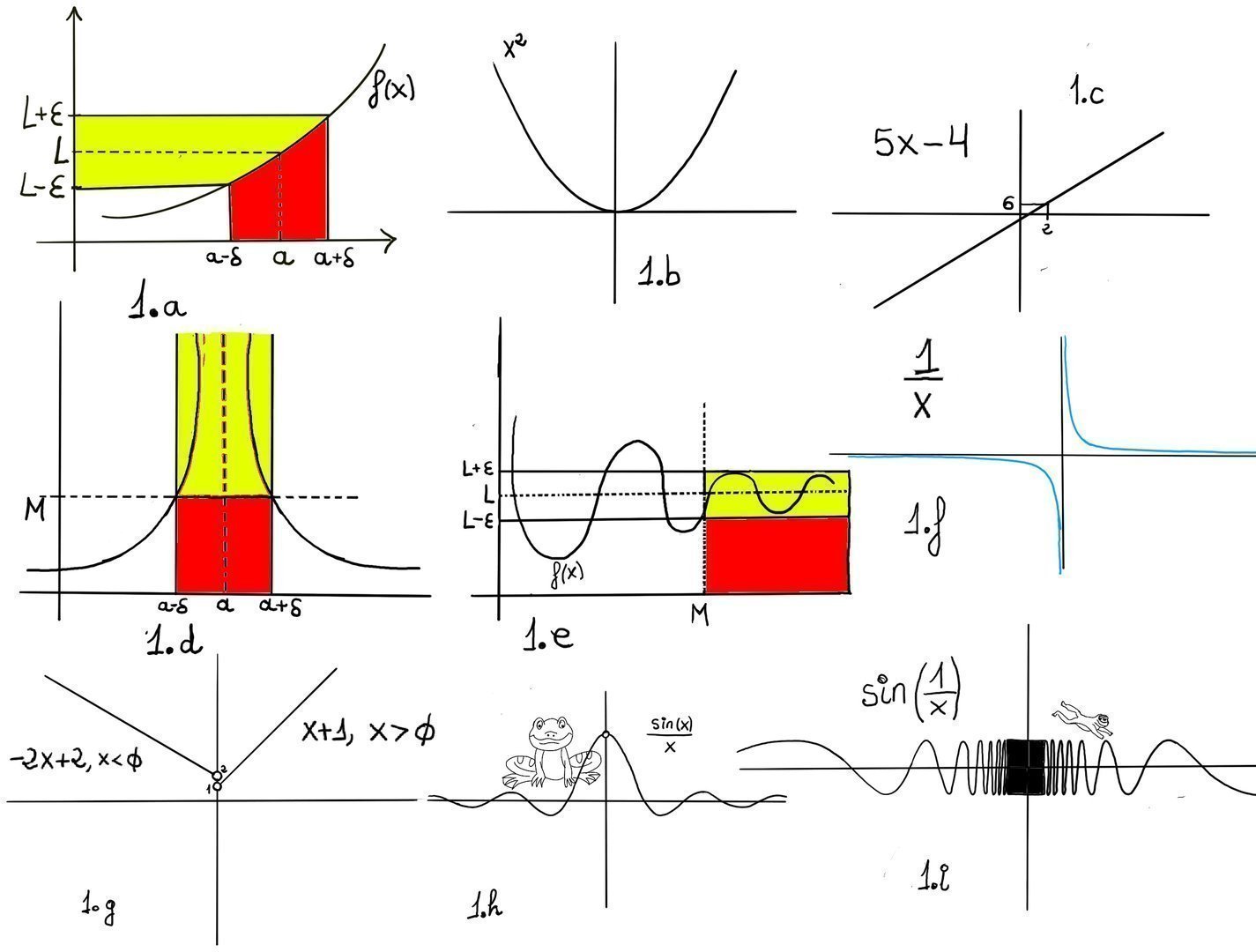

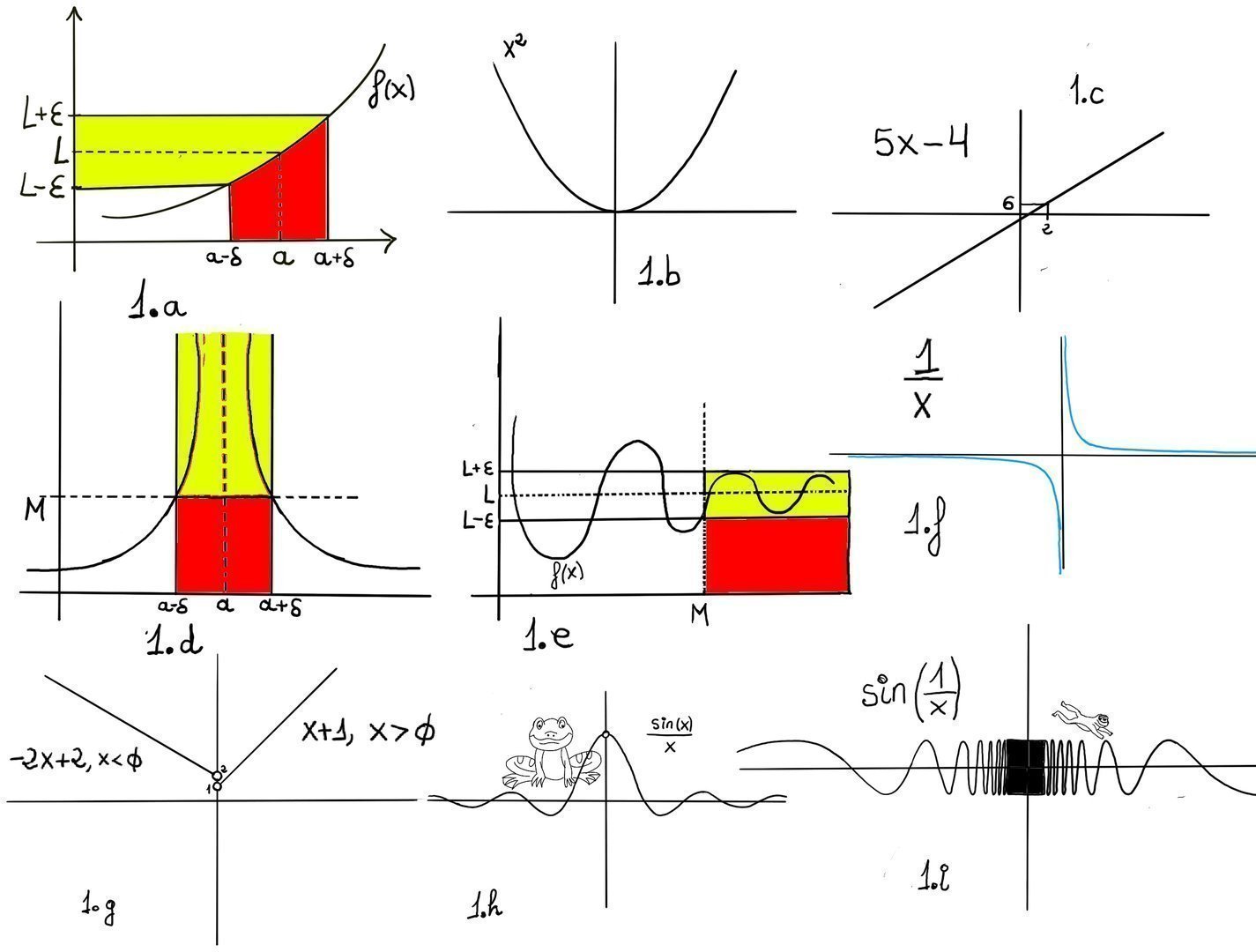

Similarly, $\lim_{x \to 0} x^2 = 0$ (Figure 1.b) and $\lim_{x \to 2} 5x -4 = 5·2 -4 = 6$ (Figure 1.c) because both functions are continuous everywhere.

Now consider the function $g(x) = \frac{x^2-1}{x-1}$. g(x) is a line, namely x + 1, but the function is undefined at x = 1, since division by zero is not allowed. In fact, Dom(g) = ℝ - {1}.

However, $\lim_{x \to 1} \frac{x^2-1}{x-1}$ =[If x ≠ 1 we can simplify] $\lim_{x \to 1} \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{x-1} = \lim_{x \to 1} x +1 = 2.$ Even though the function is not defined at x = 1, the limit exists. In fact, the function is begging to be redefined as f(x) = x + 1, which would then be defined for all real numbers.

Consider the function $f(x) = \begin{cases} 3x + 1, &x ≠ 2\\\\\\\\ 2, &x < 0 \end{cases}$

To calculate the limit $\lim_{x \to -2}$, we look at the expression used near x = 2, namely 3x + 1, so $\lim_{x \to -2} f(x) = \lim_{x \to -2} (3x + 1) = -6 +1 = -5.$ Notice that the value f(2) = 2 plays no role in the limit.

Finally, let $f(x) = \begin{cases} -2x + 2, &x < 0 \\\\ x + 1, &x > 0 \end{cases}$ (Figure 1.g.)

Approaching 0 from the left (x < 0), f(x) becomes -2x + 2 and we get closer and closer to 2: $\lim_{x \to 0^-} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 0^-} -2x + 2 = 0$. Approaching 0 from the right (x > 0), f(x) becomes x + 1 and we get closer and closer to 1: $\lim_{x \to 0^+} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 0^+} x + 1 = 1$.

Since the left-hand and right-hand limits are different, the limit does not exist: $\lim_{x \to 1} f(x)$ does not exist because the left and right limits are not equal. A limit exists at a point if and only if both one-sided limits exist and are equal —regardless of whether the function is defined at that point.

When you evaluate a limit by looking at a graph you are asking: What value does f(x) get closer and closer to when x approaches a given point? The graph gives immediate visual clues — but you must be careful to check behaviour from both sides of the point, e.g., $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{sin(x)}{x} = 1$

Given a graph of f and a point a:

We say that the limit of f, as x approaches a, is L, and write $\lim_{x \to a}f(x) = L$. For every real ε > 0, there exists a real δ > 0 such that whenever 0 < | x − a | < δ we have | f(x) − L | < ε. In other words, we can make f(x) arbitrarily close to L, f(x)∈ (L-ε, L+ε) (within any distance ε > 0) by making x sufficiently close to a (within some distance δ > 0, but not equal to a) (x ∈ (a-δ, a+δ), x ≠ a) -Fig 1.a.-

Graphically, one can draw a horizontal band (L − ε, L + ε) around L; there should exist a vertical interval or band (a − δ, a + δ) (punctured at or excluding a) such that the graph of f in that vertical strip (except possibly a) lies entirely inside the given horizontal band.

Alternative definition. Let f(x) be a function defined on an interval that contains x = a, except possibly at x = a, then we say that, $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L$ if $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: 0 < |x-a| <\delta \implies |f(x)-L|<\epsilon$

Right-hand limit. $\displaystyle\lim_{x\to a^+} f(x)=L$ means that for every $\varepsilon>0$ there exists $\delta>0$ such that if $0 < x-a < \delta$ then $|f(x)-L| < \varepsilon$.

Left-hand limit. $\displaystyle\lim_{x\to a^-} f(x) = L$ means that for every $\varepsilon>0$ there exists $\delta>0$ such that if $0 < a-x < \delta$ then $|f(x)-L|<\varepsilon$.

Infinite limit. $\displaystyle\lim_{x\to a} f(x)=+\infty$ means that for every M > 0 there exists $\delta>0$ such that if $0 < |x-a| < \delta$ then f(x) > M, (Similar for $-\infty$.)

Finding a limit by factoring is a technique to computing limits that works by canceling out common factors. It allows us to transform an indeterminate form into one that allows for direct evaluation. Notice that the limit as x approaches -2 has nothing no to do with the value of the function at x = -2.

$\lim_{x \to 2}\frac{x^2-4}{x-2} =\lim_{x \to 2}\frac{(x+2)(x-2)}{x-2} = \lim_{x \to 2}(x+2) = 4$A limit $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ exists iff both one-sided limits exist and are equal.