|

|

|

Mathematics is not about numbers, equations, computations, or algorithms: it is about understanding, William Paul Thurston.

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

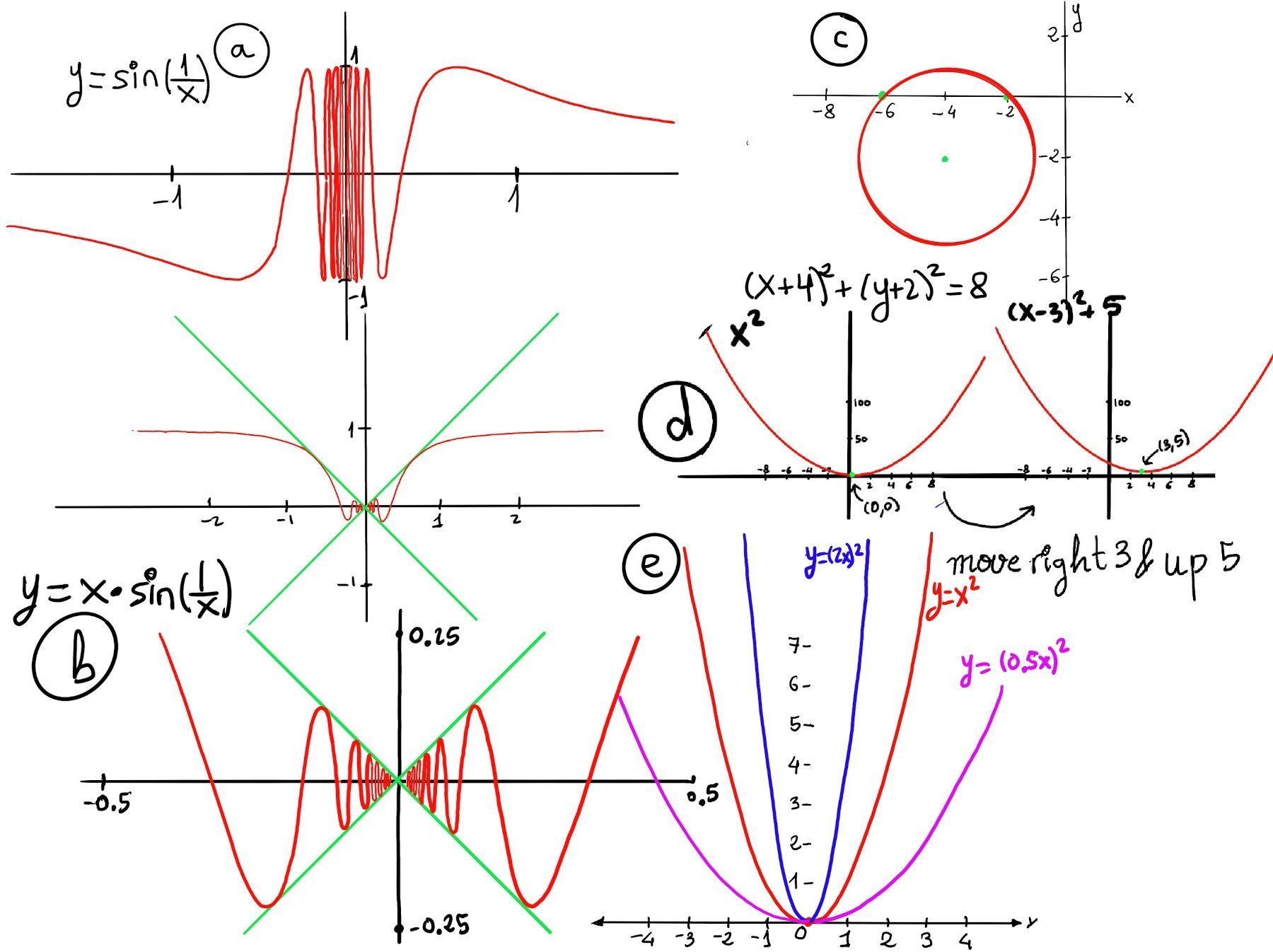

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

When we study the graph of a function, two of the most important key features or “landmarks” are the x-intercepts and the y-intercept. They tell us where the graph crosses the coordinate axes.

Definition. The x-intercept of a graph is any point on the graph that intersects the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. Equivalently, a point of the form (x, 0) that satisfies the equation of the graph.

An x-intercept is a solution of the equation f(x) = 0. The x-coordinate of such a point is often called a root or zero of the function f.

Definition. The y-intercept of a graph is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0. Equivalently, it is the point of the form (0, y) with x = 0 that lies on the graph.

Since a function must pass the vertical line test (for each x there is at most one y), a function can have at most one y-intercept. It may have no y-intercept (if x = 0 is not in the domain), but if it has one, it is unique.

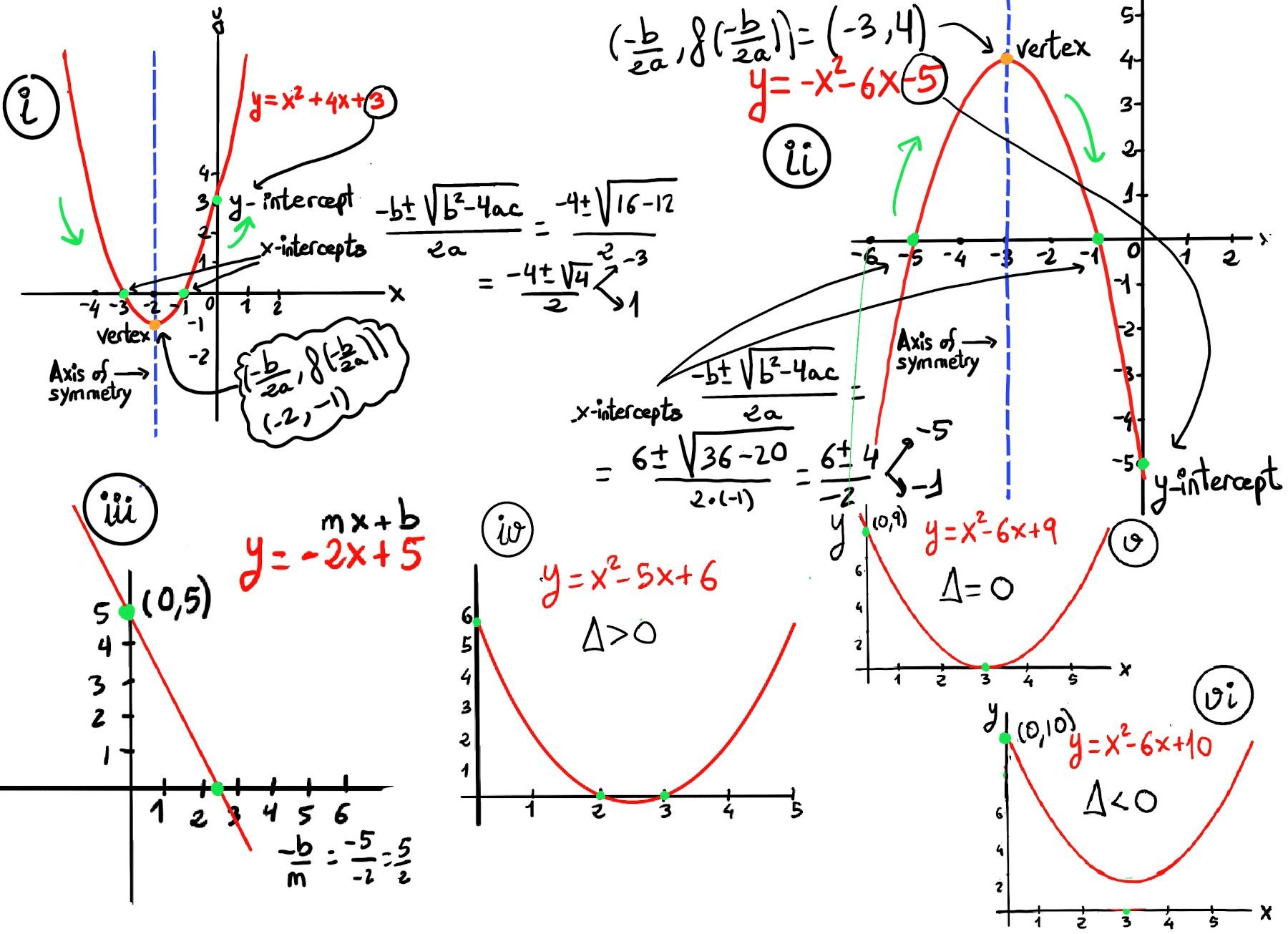

Consider a linear function written in slope–intercept form: y = mx + b, where m is the slope and b is the y-intercept. The x-intercept is the solution to the equation 0 = mx +b, that is, x= −b/m (provided m ≠ 0), e.g., y = 2x -6, set y = 0: 0 = 2x −6 ⇒ 2x = 6 ⇒ x = 3, so the x-intercept is (3, 0); y = -2x + 5 (Figure iii), the x-intercept is x = -5/-2 = 5/2, that is, (2.5, 0).

Let the equation of a graph be y = -2x + 5. If you want to find the y-intercept, set x = 0 ⇒ y = -2(0) + 5 ⇒ y = 5. Therefore, the y-intercept is (0, 5) (Figure iii).

A linear function is a function of the form y = mx + b, where m is the slope of the line, b is the y-intercept, and $\frac{-b}{m}$ is the x-intercept (if m ≠ 0).

Sometimes lines are given in standard form: Ax + By = C. Example: 2x -4y = 8. Its alternate form is 4y = 2x -8 ↭ $y = \frac{2x}{4}-\frac{8}{4} ↭ y = \frac{x}{2}-2$, So the y-intercept is (0, −2) and, $\frac{-b}{m} = \frac{2}{\frac{1}{2}} = 4$, so the x-intercept is (4, 0).

For a quadratic function $y = ax^2 +bx +c, a \ne 0$, its x-intercepts are the solutions of the quadratic equation $y = ax^2 +bx +c = 0$. We can find these using the quadratic formula: x = $\frac{-b±\sqrt{b^2-4ac}}{2a}$. The discriminant (Δ = b2 -4ac) can be used to calculate the number of x-intercepts and the type of solutions or x-intercepts of the quadratic equation.

Besides, for a quadratic equation written in standard form y = ax2 +bx +c , the y-intercept is (0, c). The graph of a quadratic function ax2 + bx + c is a parabola. It has an extreme point, called the vertex, where the curve changes direction.

If the parabola opens upwards (a > 0), the vertex represents the lowest point on the curve and its y-coordinate is the minimum value of the quadratic function. If the parabola opens downwards (a < 0), the vertex represents the highest point on the curve, and its y-coordinate is the maximum value of the quadratic function. In either case, the vertex is a turning point on the graph. The graph is also symmetric with a vertical line drawn through the vertex, called the axis of symmetry: $x = \frac{-b}{2a}$, So, the graph of the function is increasing on one side of the axis and decreasing on the other side.

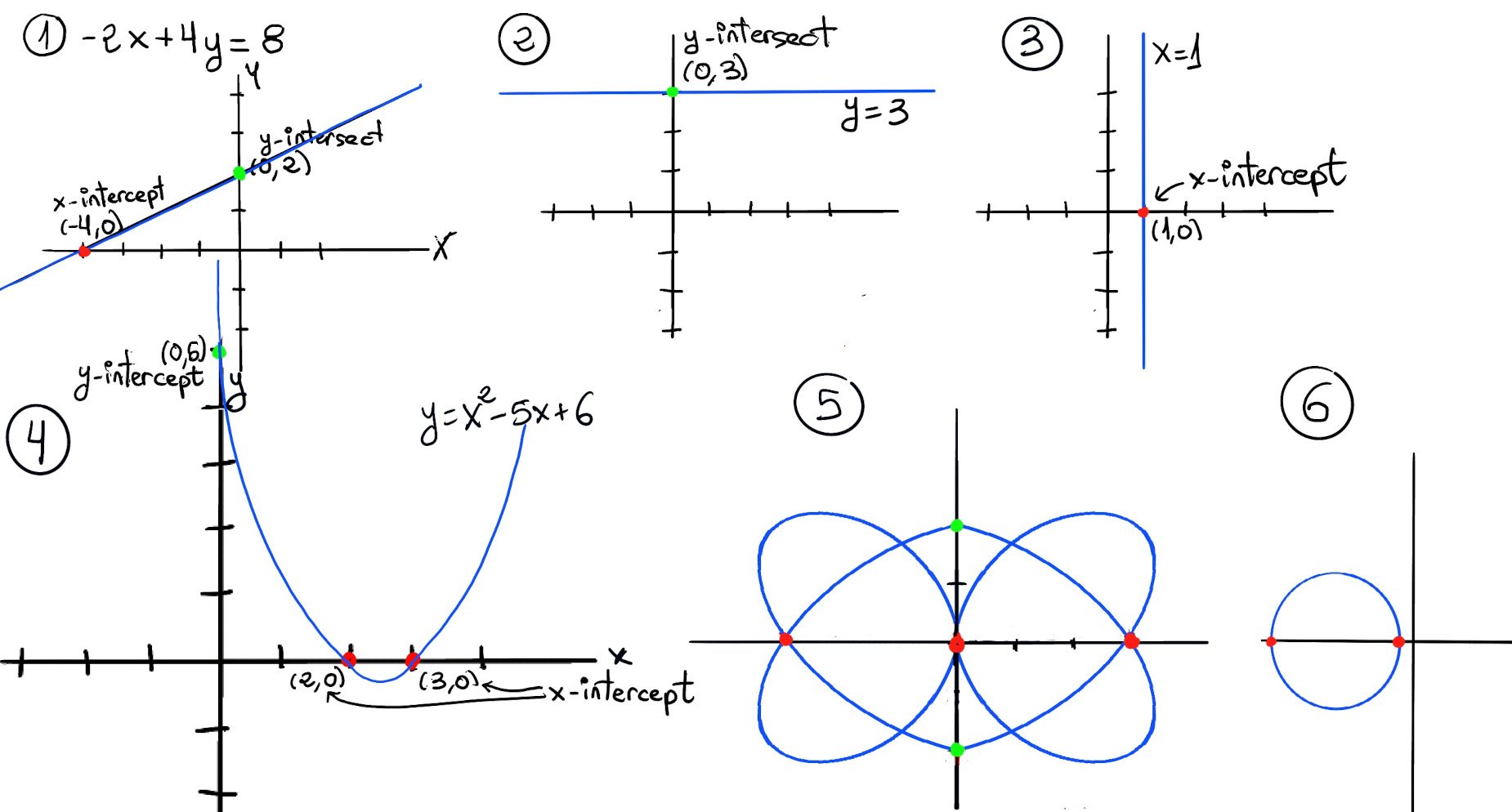

Let’s find the x- and y-intersect of -2x + 4y = 8. To find the x-intercept, set y = 0 ⇒ -2x = 8 ⇒ x = $\frac{8}{-2}=-4$, that is, the x-intersect is (-4, 0). To find the y-intercept, set x = 0 ⇒ 4y = 8 ⇒ y = 2, so the y-intersect is (0, 2), Figure 1.

A completely similar example, 5x + 2y = 10. To find the x-intercept, set y = 0 ⇒ 5x = 10 ⇒ x = $\frac{10}{5}=2$, that is, the x-intercept is (2, 0). To find the y-intercept, set x = 0 ⇒ 2y = 10 ⇒ y = 5, so the y-intercept is (0, 5).

Not all graphs necessarily have both intercepts: the horizontal line y = 3 has an y-intercept at (0, 3) and no x-intercept (it never crosses the x-axis), but the vertical line x = 1 has a x-intercept at the point (1, 0) and no y-intercept (Figure 2 and 3 respectively).

Vertical lines like x = 1 are not functions; they fail the vertical line test because one input x = 1 has infinitely many possible y-values.

The graph of the quadratic function y = x2 -5x + 6 intersects the x-axis in two places, namely (2, 0) and (3, 0). Its only y-intercept is (0, 6) -Figure 4-.

Figure 5 and 6 illustrate that even though those graphs do not determine functions (they fail to pass the vertical test), they still have x- and y-intercepts (the circle do not have y-intercepts).

The x-intercepts are represented by red circles ((-3, 0), (0, 0), (0, 3) -Figure 5-, (-5, 0), (-1, 0) -Figure 6-) and the y-intercepts by green circles ((0, 2) and (0, -2) -Figure 5-).

If the graph passes through the origin (0,0), it has both an x-intercept and a y-intercept at the origin.

The reciprocal function $y = \frac{1}{x}$ has no intercepts because it is undefined at x = 0 (so it never crosses the y-axis) and $\frac{1}{x} = 0$ has no solution (so the graph never crosses or touches the x-axis). Asymptotes: x = 0 and y = 0.

The graph of the sine function, y = sin(x), has infinitely many x-intercepts at $x = \dots, -2\pi, -\pi, 0, \pi, 2\pi, 3\pi, \dots$ (i.e., $x = k\pi$, $k \in \mathbb{Z}$).

Exponential functions $y = a^x$ (with $a > 0$, $a \neq 1$) have no x-intercepts (exponential functions never cross the x-axis) but exactly one y-intercept at $(0,1)$ (Substituting x = 0: $y=a^0=1$). So the graph always passes through the point (0, 1).

Let’s find the x- and y-intersect of (x + 4)2 + (y + 2)2 = 8 (Figure c).

x-intercepts; set $y = 0$ and solve for x:

$$ \begin{align*} (x + 4)^2 + (0 + 2)^2 &= 8 \\ (x + 4)^2 + 4 &= 8 \\ (x + 4)^2 &= 4 \\ x + 4 &= \pm 2 \\ x &= -4 \pm 2 \end{align*} $$The x-intercepts are: $(-6, 0)$ and $(-2, 0)$

y-intercepts; set $x = 0$ and solve for y:

$$ \begin{align*} (0 + 4)^2 + (y + 2)^2 &= 8 \\ 16 + (y + 2)^2 &= 8 \\ (y + 2)^2 &= -8 \quad (\text{impossible for real } y) \end{align*} $$$y^2 + 4y + 12 = 0$. Discriminant $b^2 - 4ac = 16 - 64 = -48 < 0$. No real y-intercepts.

(x -a)2 + (y -b)2 = r2 is the standard equation of a circle, the center is (a, b) and the radius is r. In our case, the center is (-4, -2) and the radius is $\sqrt{8} = 2\sqrt{2} ≈ 2.83$.

So the circle crosses the x-axis twice (at x = -6 and x = -2) and extends a little above the x-axis (highest point ≈ 0.83). It never reaches the y-axis because the distance from the center to the y-axis is 4 units, while the radius is only ≈ 2.83 < 4 .