|

|

|

It may be worth noting that there are no uninteresting numbers. Proof (induction): Assume there are uninteresting numbers. There must be a smallest uninteresting number. That makes it interesting, since it is the smallest uninteresting number. thus producing a contradiction.

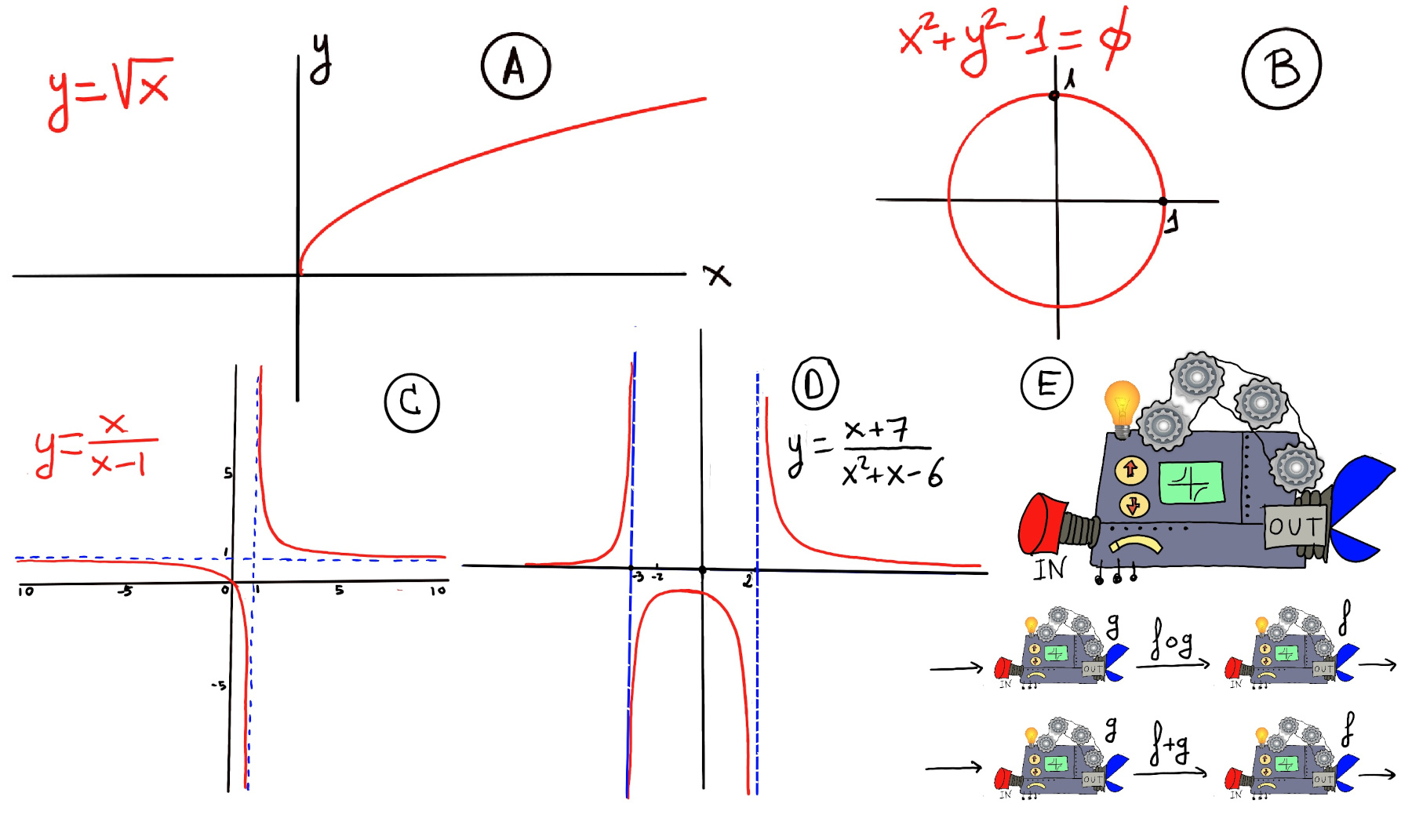

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range). A mathematical function is like a black box that takes certain input values and generates corresponding output values (Figure E).

Very loosing speaking, a limit is the value to which a mathematical function gets closer and closer to as the input gets closer and closer to some given value.

A limit describe what is happening around a given point, say “a”. It is the value that the function approaches as the input approaches “a”, and it does not depend on the actual value of the function at a, or even on whether the function is defined at “a” at all.

Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis and the understanding of how functions behave. The concept of a limit can be written or expressed as $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L.$ This notation is read as “the limit of f as x approaches a equals L”.

Intuitively, this means that the values of f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L (and I mean as close as we like, e.g., L ± 0.1, L ± 0.01, L ± 0.001, and so on), by choosing values of x sufficiently close to a, but not necessarily equal to a.

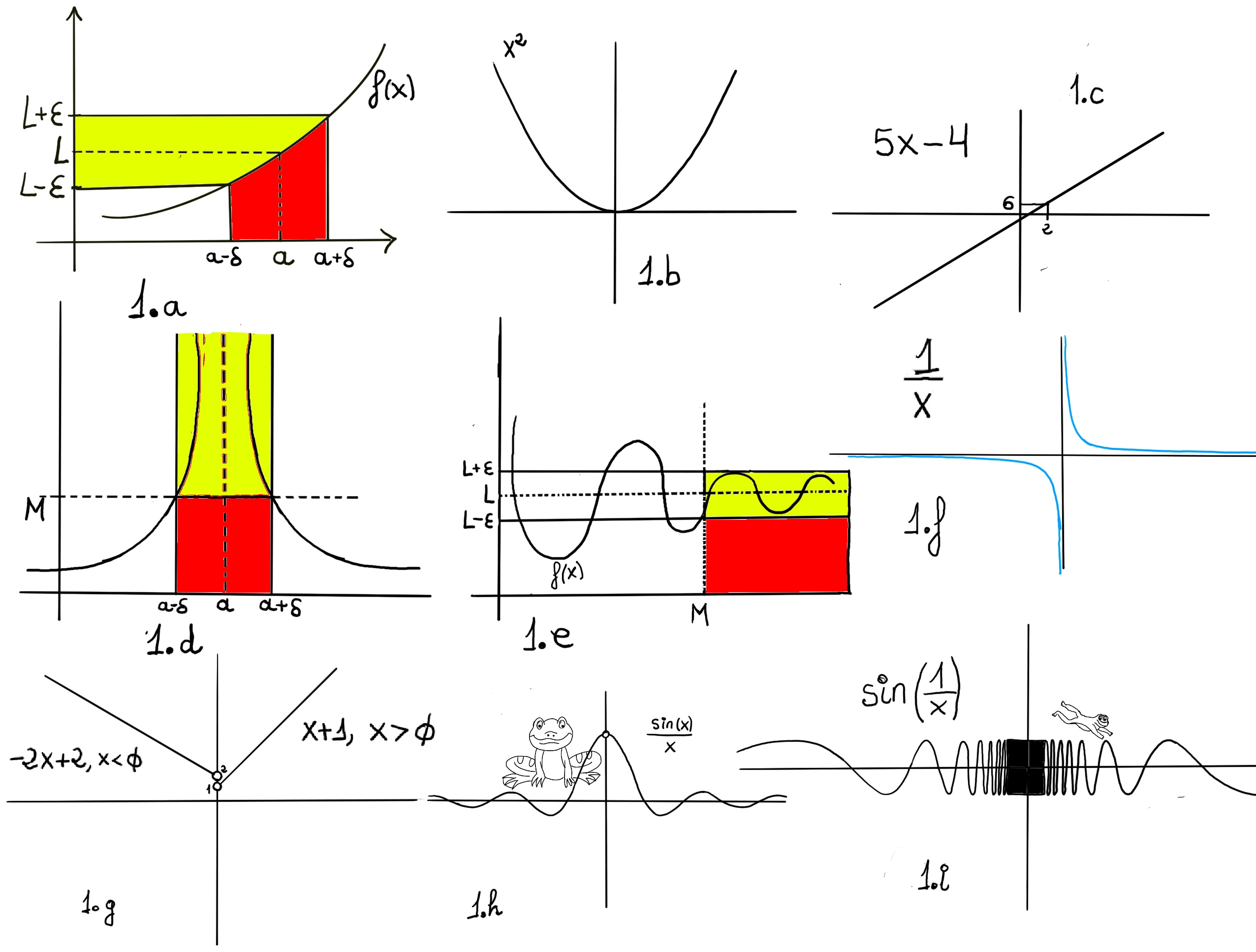

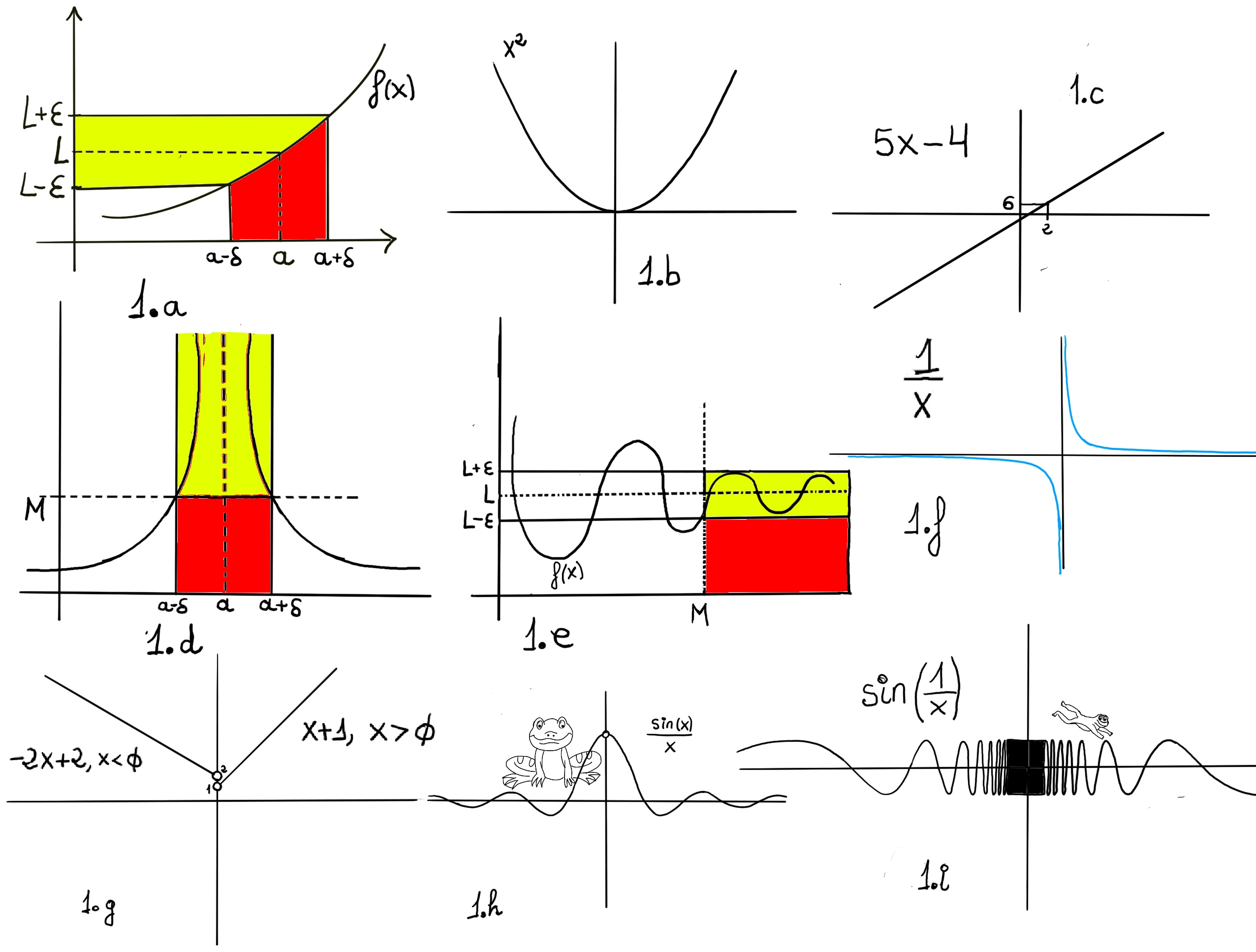

Formal definition. We say that the limit of f, as x approaches a, is L, and write $\lim_{x \to a}f(x) = L$. For every real ε > 0, there exists a real δ > 0 such that whenever 0 < | x − a | < δ we have | f(x) − L | < ε. In other words, we can make f(x) arbitrarily close to L, f(x)∈ (L-ε, L+ε) (within any distance ε > 0) by making x sufficiently close to a (within some distance δ > 0, but not equal to a) (x ∈ (a-δ, a+δ), x ≠ a) -Fig 1.a.-

In many circumstances and situations, a function may not approach a specific finite real number as x approaches a particular value. Rather, the function might become arbitrarily large (grow without bound) or decrease without bound. This behaviour is described using infinite limits.

Definition. Let f(x) be a function defined on an interval that contains x = a, except possibly at x = a. We say that, $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \infty$ if $\forall M>0, \exists \delta>0: ~\text{such that } f(x) > M, whenever~ 0<|x-a|<\delta.$ The function grows without bound as x approaches a.

Loosely speaking this definition means that we can make the value of f(x) arbitrary large (exceed any positive number M, no matter how large) by taking x sufficiently close, but never equal to a (Figure 1.d.).

Definition. Similarly, let f(x) be a function defined on an interval that contains x = a, except possibly at x = a. We say that, $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = -\infty$ if $\forall M<0, \exists \delta>0: \text{ such that } f(x) < M, whenever~ 0<|x-a|<\delta.$ The function decreases without bound as x approaches a.

Loosely speaking, this means that we can make the value of f(x) arbitrary small (smaller than any negative number M) by taking x sufficiently close, but never equal to a.

Infinite limits can also occur from only one side: $\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) = \infty, \lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = -\infty$. These describe the behavior of the function as x approaches a from the left or from the right, respectively. One-sided infinite limits are especially important when studying vertical asymptotes.

A vertical asymptote of a function y = f(x) is a vertical line x = a such that the function becomes unbounded as x approaches a.

Definition. The line x = a is a vertical asymptote of a function y = f(x) if at least one of the following holds:

A vertical asymptote is a vertical line that the graph of the function approaches arbitrarily closely, but never reaches or crosses. Near this line, the function values grow without bound (either y = f(x) tends to ∞ or -∞) in either the positive or negative direction. Vertical asymptotes indicate unbounded behavior, not holes, jumps, or removable discontinuities.

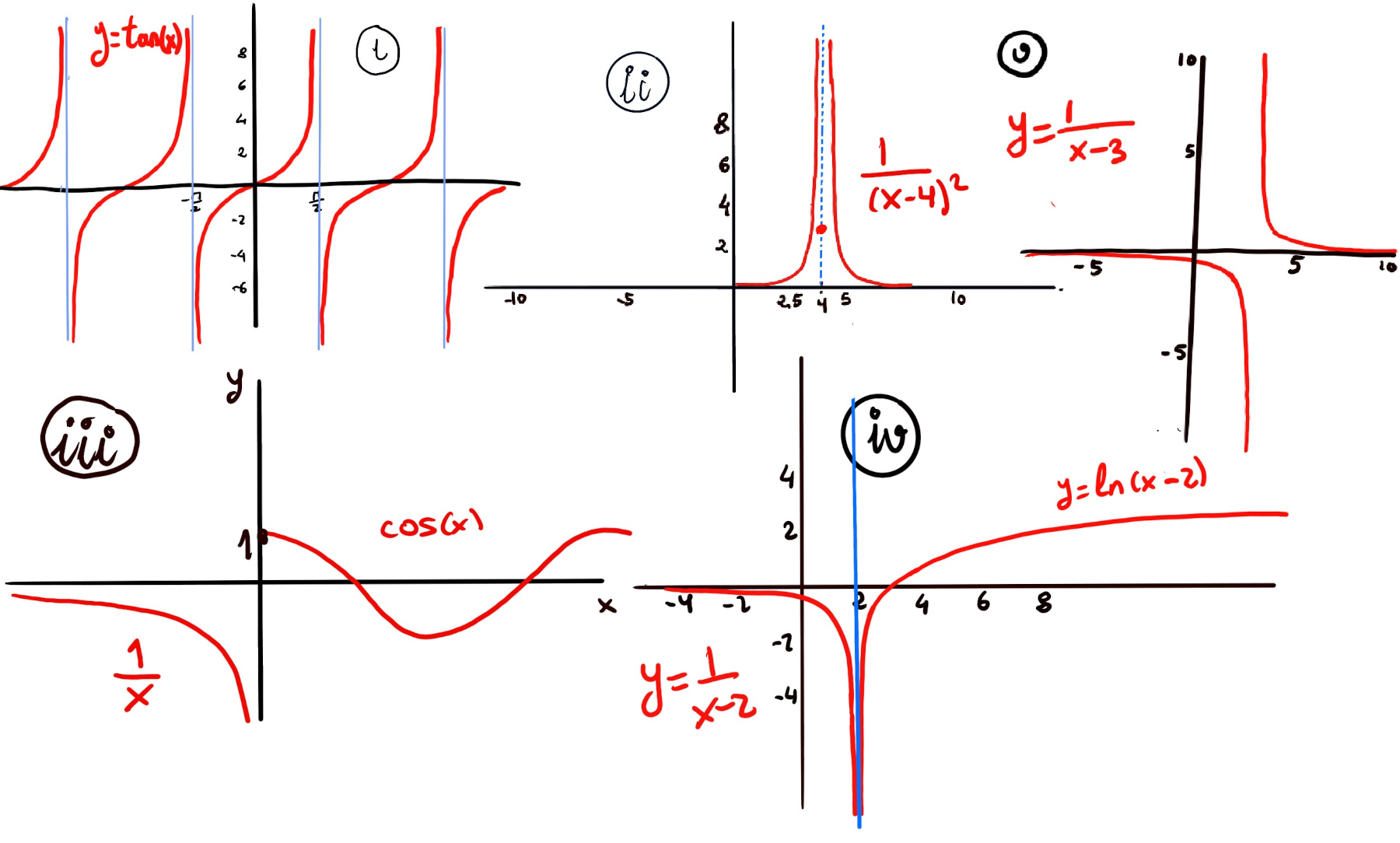

They often occur in rational functions where the denominator tends to zero while the numerator does not, e.g., $f(x) = \frac{1}{x-2}, \lim_{x \to 2^+} \frac{1}{x-2}= \infty, \lim_{x \to 2^-} \frac{1}{x-2}= -\infty$. Thus, x = 2 is a vertical asymptote, and the one-sided limits are infinite but not equal.

Not all undefined points yield vertical asymptotes —some are removable discontinuities (holes), e.g., $f(x) = \frac{x^2-4}{x-2}, lim_{x \to 2} \frac{x^2-4}{x-2} = lim_{x \to 2} x + 2 = 4.$ Thus, there is no vertical asymptote at x = 2; instead, there is a removable discontinuity (a hole).

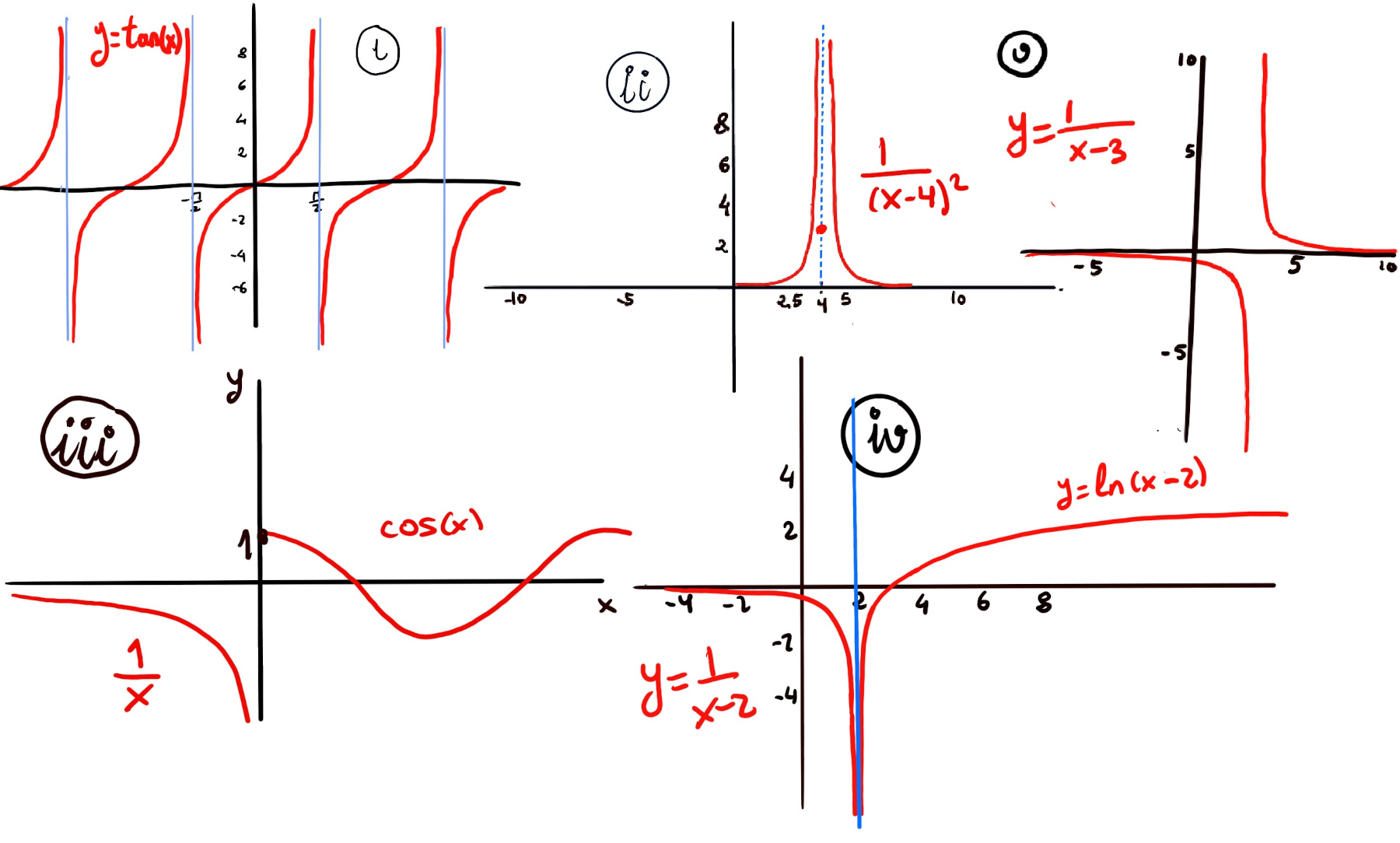

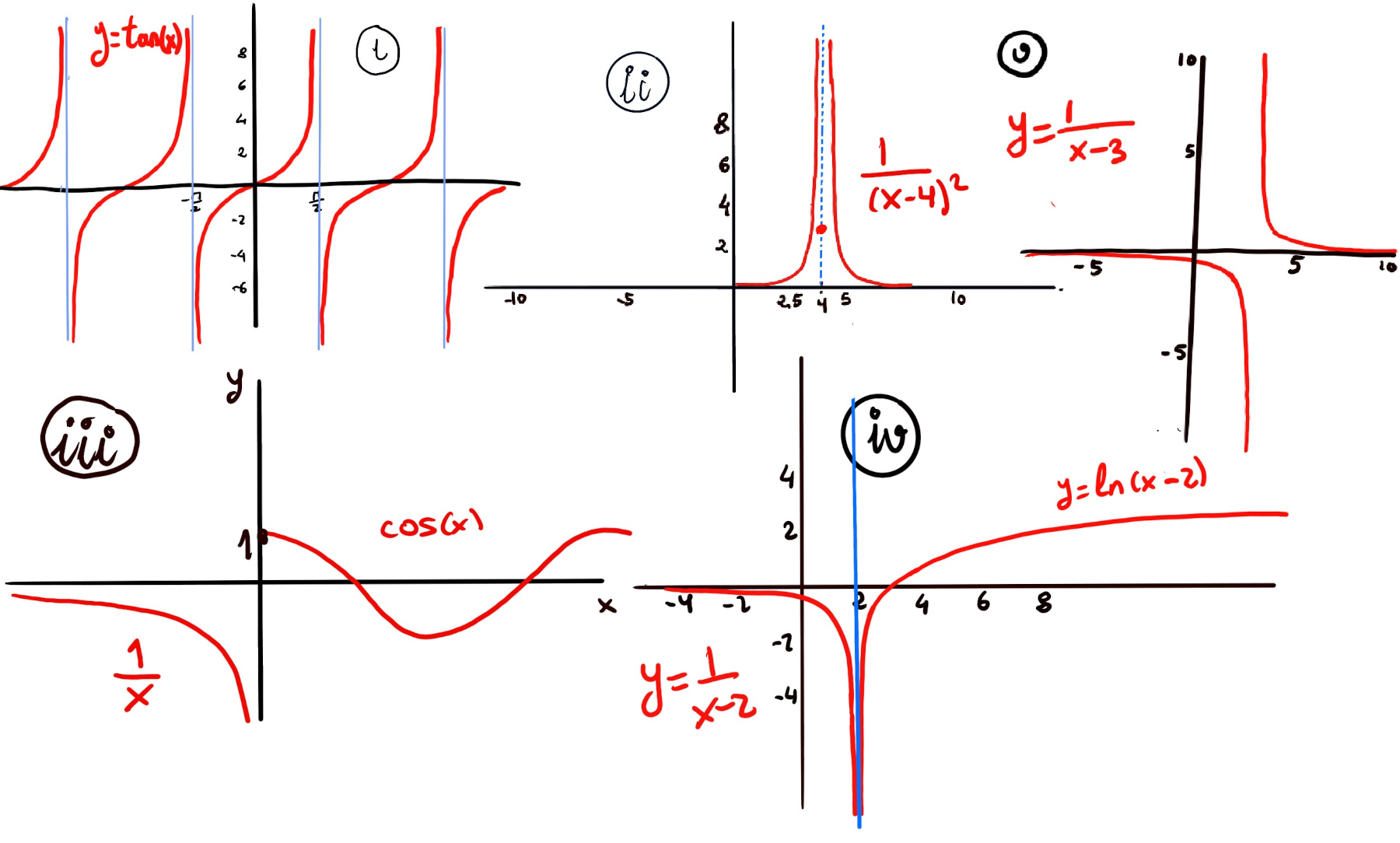

Recall that the tangent function is undefined at π/2+nπ, n ∈ ℤ, and each of these values corresponds to a vertical asymptote of the graph of tan(x).

Approaching 0 from the left (x < 0), f(x) becomes 1/x and the function decreases to minus infinity -∞, $\lim_{x \to 0⁻} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 0⁻} \frac{1}{x} = -∞$. Approaching 0 from the right (x > 0), f(x) becomes cos(x) and we get closer and closer to 1, $\lim_{x \to 0⁺} f(x) = \lim_{x \to 0⁺} cos(x) = 1$. Therefore, $\lim_{x \to 0} f(x)$ does not exist because the left and right limits are different, (figure 3).

$\lim_{x \to 2⁻} f(x) = \frac{1}{x-2} = -∞, \lim_{x \to 2⁺} f(x) = ln(x-2) = -∞$. Since both one-sided limits approach −∞, $\lim_{x \to 2} f(x) = -∞$ (Figure iv). Therefore, x = 2 is a vertical asymptote of the function.

$\forall M>0, \exists \delta>0: \frac {1}{x^{2}} > M, whenever~ 0<|x|<\delta.$

Rewriting the inequality, $\frac {1}{x^{2}} > M \iff x^2 \lt \frac{1}{M}$

This suggests choosing $\boxed{\delta = \frac{1}{\sqrt M}}$

$\forall M>0, \exists \delta = \frac {1}{\sqrt M}>0: \frac {1}{x^{2}} > M, whenever~ 0<|x|<\frac {1}{\sqrt M}.$

Now verify: $|x|<\frac {1}{\sqrt M} ⇨ |x|^{2}<\frac {1}{M} ⇨ x^{2}<\frac {1}{M} ⇨ M <\frac{1}{x^{2}}$

Because this is a right-hand limit, we must show that: $\forall M>0, \exists \delta>0: f(x)>M, whenever~ a < x < a + \delta.$

$\forall M>0, \exists \delta>0: \frac{1}{x-3}>M, whenever~ 3 < x < 3 + \delta$

$3 < x < 3 + \delta$ ⇒ 0 < x - 3 < δ ⇒[Since x−3 is positive in this interval, taking reciprocals reverses the inequality:] $\frac{1}{x-3} > \frac{1}{δ}$ ⇒[Let’s choose $\boxed{\delta = \frac{1}{M}}$] = $\frac{1}{\frac{1}{M}} = M.$

$\forall M>0, \exists \delta>0: \frac{x}{2x-2}>M, whenever~ 0 < x -1 < \delta$

$0 < x -1 < \delta ⇒ \frac{1}{x-1}>\frac{1}{\delta}$[🚀]

$\frac{x}{2x-2} = \frac{x}{2}\frac{1}{x-1}>🚀\frac{x}{2}·\frac{1}{\delta} >$ [0 < x -1 ⇒ x > 1 ⇒ x⁄2 > 1⁄2] $\frac{1}{2δ} =$ [Thus, we should choose $\boxed{\delta = \frac{1}{2M}}$] M.