|

|

|

You’ve gotta dance like there’s nobody watching, love like you’ll never be hurt,sing like there’s nobody listening, and live like it’s heaven on earth, William W. Purkey.

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

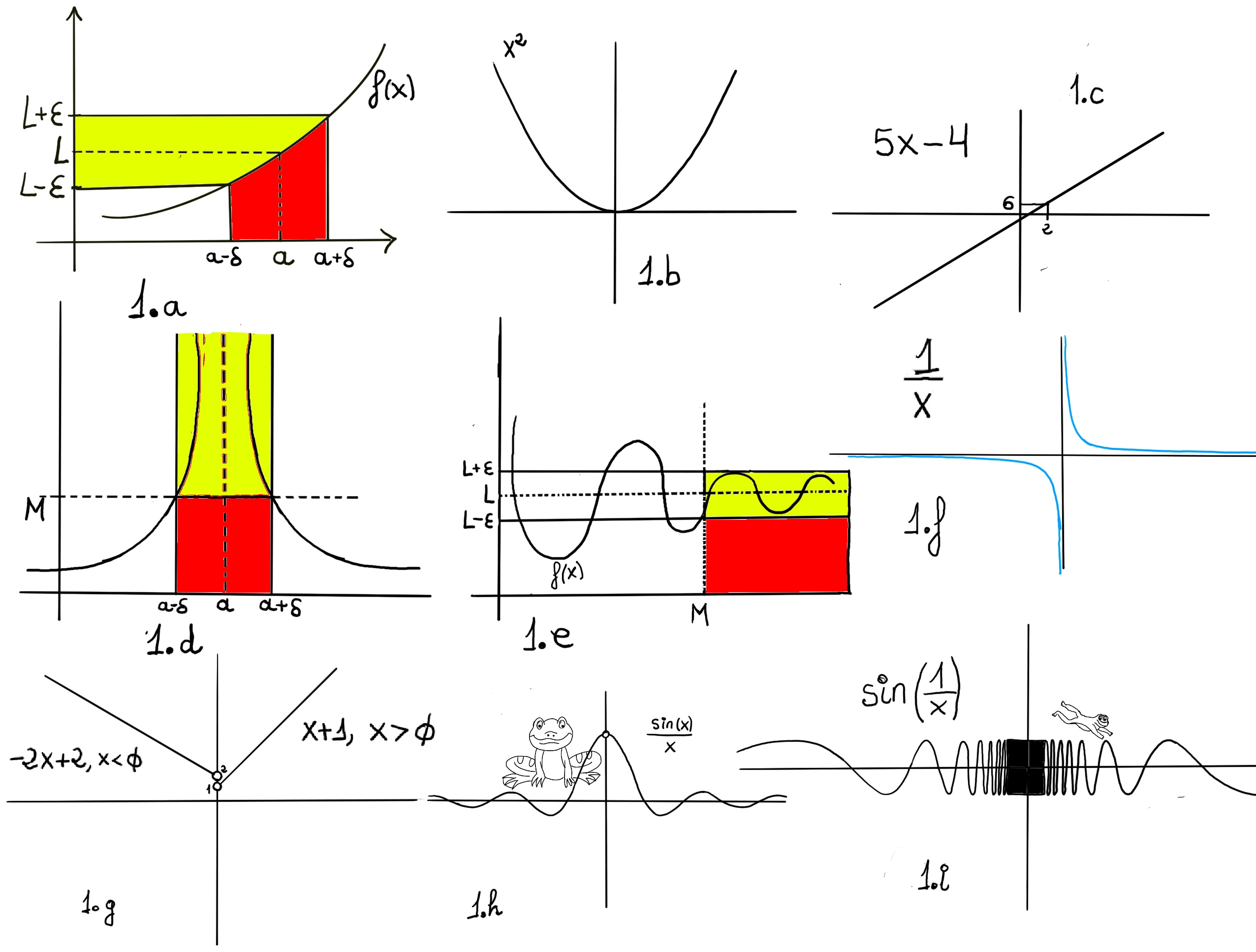

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ. A mathematical function can be thought of as a black box (or machine) that takes an input from its domain and produces exactly one output in its codomain. Inside the machine lives a specific rule (formula, procedure, or mapping) that dictates or tells you which output corresponds to each input, and a key property is uniqueness —each input maps to a single, deterministic output. No input can ever produce two different results (Figure E). The function f(x) = x2 accepts any real number x (domain: ℝ) and returns exactly one non-negative value x2 (output in codomain: [0,∞)). The input 3 always yields 9, never any other value.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

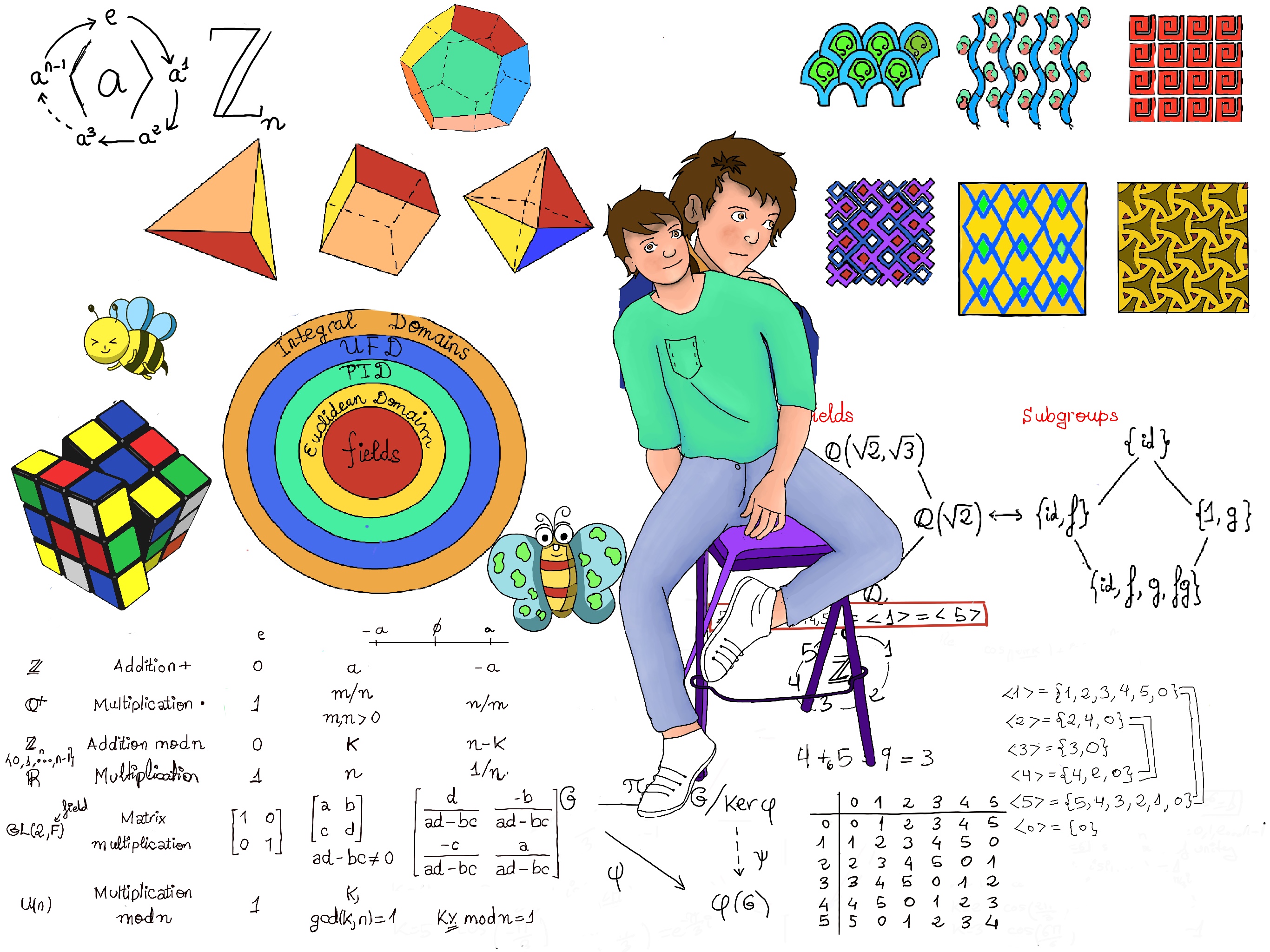

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$.💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

First Derivative Test. Let f be differentiable on an open interval containing c, except possibly at c itself, and let c be a critical point (so f′(c) = 0 or f′ is undefined). Then:

Continuity is one of the most fundamental ideas in calculus. Intuitively, continuity formalizes the notion of a function whose graph has no breaks, jumps, or gaps, and whose values change smoothly as the input changes.

Definition. A function f(x) is continuous at a point x = a if and only if the following three conditions are satisfied:

A function is continuous at a point if the value of the function agrees with the value the function is approaching. If any one of these conditions fails, the function is discontinuous at x = a.

Definition. A function is continuous on an open interval (a,b) if it is continuous at every point on that interval (a, b).

Definition. A function is continuous on a closed interval [a, b] if it is continuous on the open interval (a,b), continuous from the right at a (i.e., $\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = f(a)$), and continuous from the left at b (i.e. $\lim_{x \to b^-} f(x) = f(b)$).

Geometrically, you can think of a function that is continuous as a function whose graph has no breaks, holes, or jumps. Intuitively, f is continuous at a if as x gets closer and closer to a, f(x) gets closer and closer to f(a).

Continuous functions possess key properties that make them indispensable in calculus and applications:

The rigorous definition of continuity is given using ε–δ language.

Formally, let f(x) be a function defined on an interval that contains x = a, then we say that f(x) is continuos at x = a, if $\forall \epsilon>0, \exists \delta>0: ~(such~that)~ |f(x)-f(a)|<\epsilon, whenever~ |x-a| < \delta.$ This definition states that we can make f(x) arbitrarily close to f(a) by choosing x sufficiently close to a.

A function is discontinuous if you cannot draw its graph without lifting your pen. The function’s graph does not form a continuos line, but instead has gaps such as jumps, holes, or breaks. More formally, a function is discontinuous at a point a if it fails to be continuous at a, that is, when it breaks any of the continuity criteria, such as,

Discontinuities appear as holes, jumps, vertical asymptotes, or erratic oscillations.

Discontinuities can be classified according to how continuity fails.

$f(x) = \begin{cases} x + 1, &x > 0\\\\\\\\ -2x + 2, &x < 0 \end{cases}$ -1.g.-

$\lim_{x \to 0^{+}} f(x) = 1 ≠ 2 = \lim_{x \to 0^{-}} f(x).$

$f(x) = \begin{cases} -x^{2} + 4, &x≤3\\\\\\\\ 4x - 8, &x > 3 \end{cases}$

$\lim_{x \to 3^{+}} f(x) = 4 ≠ -5 = \lim_{x \to 3^{-}} f(x).$

$\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{sin(x)}{x} = 1$, but f(0) is not defined. If we redefine f(0) = 1, the discontinuity is removed, and the function becomes continuous at x = 0.

$\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{sin(x)}{x} = 1$, but f(0) is not defined. If we redefine f(0) = 1, the discontinuity is removed, and the function becomes continuous at x = 0.

f(x) = $\frac{x^{2}-4}{x-2}$. $\lim_{x \to 2}\frac{x^{2}-4}{x-2} = \lim_{x \to 2}\frac{(x-2)(x+2)}{x-2} = \lim_{x \to 2} (x+2) = 4,$ but f(2) is undefined.

$f(x) = \begin{cases} 2x + 1, &x<1\\\\\\ 2, &x=1\\\\\\ -x + 4, &x > 1 \end{cases}$

$\lim_{x \to 1^{+}} f(x) = 3 = \lim_{x \to 1^{-}} f(x), but \lim_{x \to 1} f(x) = 3 ≠ 2 = f(1)$

y = $\frac{1}{x}$ -1.f.-, $\lim_{x \to 0^{+}} \frac{1}{x} = \infty$ and $\lim_{x \to 0^{-}} \frac{1}{x} = -\infty$

y = $\frac{x+2}{x+1}$, $\lim_{x \to -1^{+}} \frac{x+2}{x+1} = \infty$ and $\lim_{x \to -1^{-}} \frac{x+2}{x+1} = -\infty$

f(x) = $\frac{1}{(x-2)^2}, \lim_{x \to 2^{+}} \frac{1}{(x-2)^2}=\lim_{x \to 2^{-}} \frac{1}{(x-2)^2} = \infty$.

f(x) = $\tan(x), \lim_{x \to \frac{\pi}{2}^{-}}\tan(x) = \infty, \lim_{x \to \frac{\pi}{2}^{+}} \tan(x)= -\infty$

These correspond to vertical asymptotes.

Theorem. If a function f is differentiable at x = a, then f is continuous at x = a.

Proof. We need to check if $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = f(a) ↔ \lim_{x \to a} f(x) - f(a) = 0$

$\lim_{x \to a} f(x) - f(a) = \lim_{x \to a} \frac {f(x) - f(a)}{x - a}(x-a) =$[By assumption, f’(a) exists and also $\lim_{x \to a}(x-a) = 0$] f’(a)·0 = 0.

The converse is not true. A function can be continuous but not differentiable, e.g., f(x)=∣x∣ is continuous at x = 0, but f’(0) does not exist.