|

|

|

Older people shouldn’t eat health food, they need all the preservatives they can get, Robert Orben.

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

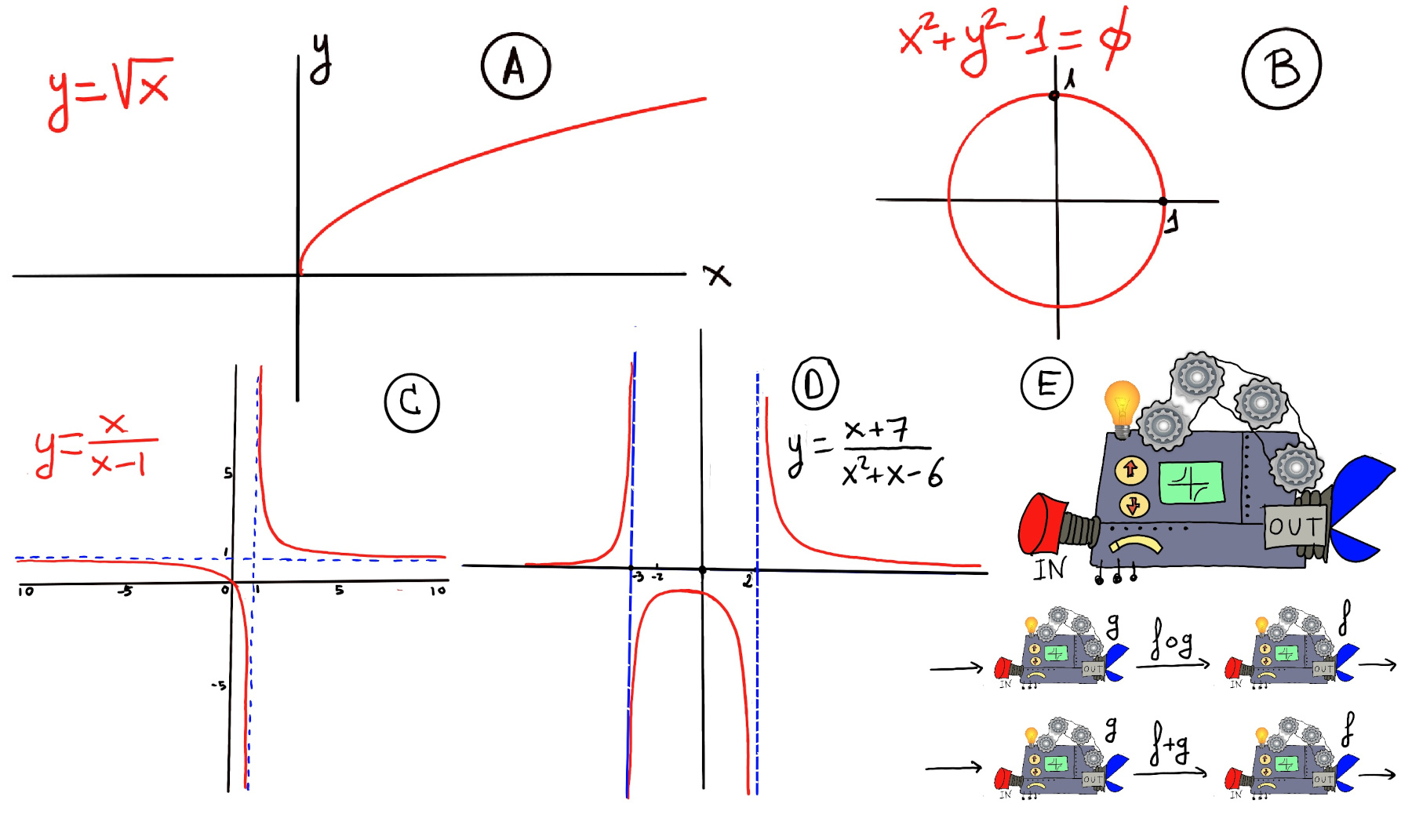

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ. A mathematical function can be thought of as a black box (or machine) that takes an input from its domain and produces exactly one output in its codomain. Inside the machine lives a specific rule (formula, procedure, or mapping) that dictates or tells you which output corresponds to each input, and a key property is uniqueness —each input maps to a single, deterministic output. No input can ever produce two different results (Figure E). The function f(x) = x2 accepts any real number x (domain: ℝ) and returns exactly one non-negative value x2 (output in codomain: [0,∞)). The input 3 always yields 9, never any other value.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

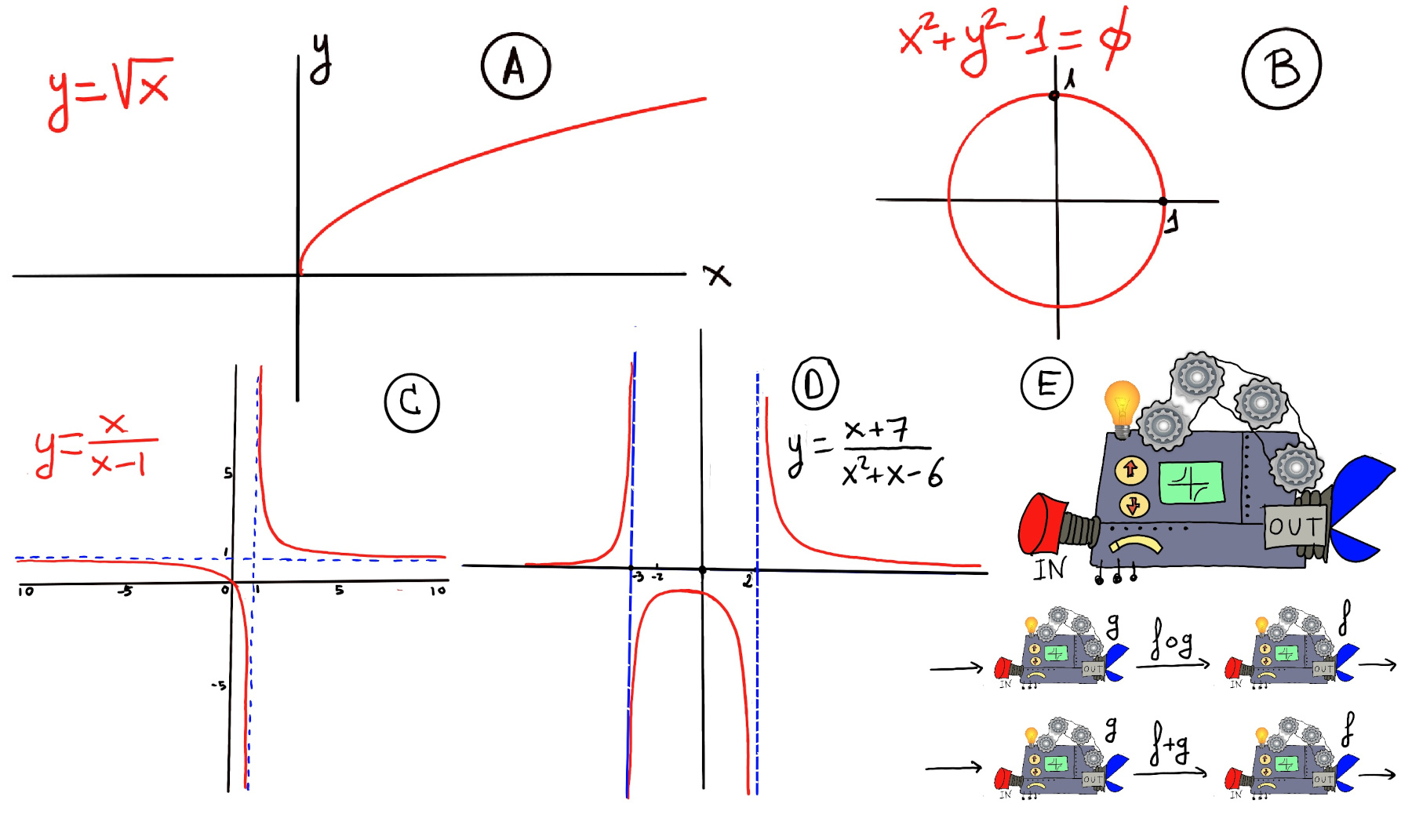

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

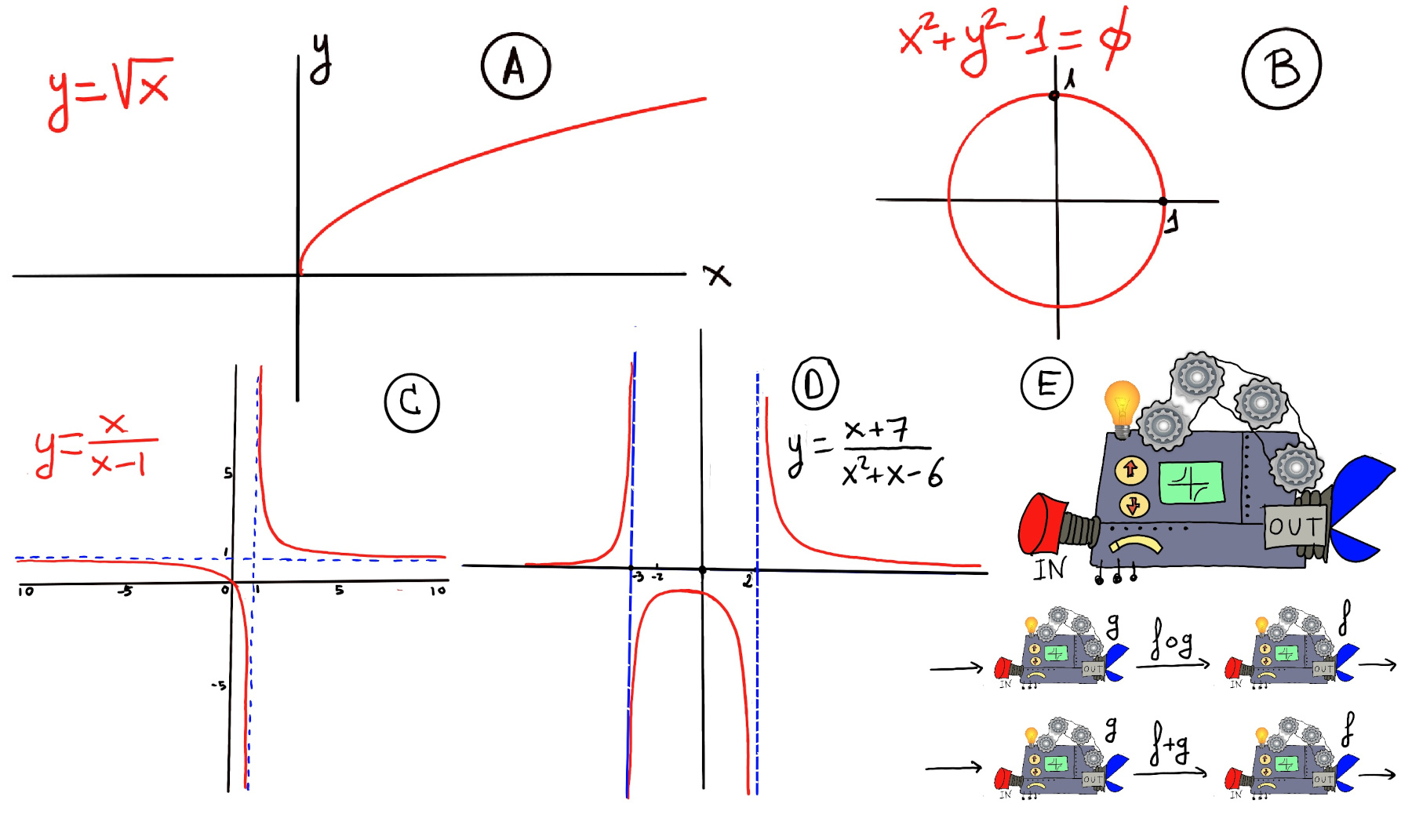

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$.💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

First Derivative Test. Let f be differentiable on an open interval containing c, except possibly at c itself, and let c be a critical point (so f′(c) = 0 or f′ is undefined). Then:

Algebra of functions involves operations and manipulations applied to functions. Consider the scenario where we aim to sum the individual annual incomes of both a husband and a wife to obtain their total household income for each year. If w(x) signifies the wife’s income and h(x) denotes the husband’s income, and we wish to express the total income as T, we can define a new function, T(x) := h(x) + w(x).

We can combine existing functions. One way is to use function composition where we evaluate or apply one function to another, that is, where we take the output of one function and feed it into another, (e.g., sin(x2), log(1⁄x), $\sqrt{1-x^2}$). Another way is to carry out the basic four arithmetic operations on functions. For any arithmetic operation of two functions at an input, we just have to apply the same operation with the function outputs (Figure E).

Algebra of functions means creating new functions from old ones by performing algebraic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division), scalar multiplication, and composition. These operations are performed pointwise.

Let f and g be real-valued functions. For every x in the appropriate domain define:

For doing any arithmetic operation of two functions, their domains must be the same (it is typically the set of all real numbers, ℝ) or the intersection of their domains. Imagine two machines (functions) that process raw materials (inputs) where machine f works on materials from 8 AM to 5 PM (its domain) and machine g works from 10 AM to 6 PM (its domain). If you want to run both machines simultaneously (add their outputs), you can only operate during 10 AM to 5 PM —the intersection of their working hours!

Difference: (f - g)(x) = f(x) - g(x). Domain(f - g) = Domain(f) ∩ Domain(g). Examples: f(x) = x2, g(x) = x -1, (f - g)(x) = x2 -x +1, Domain: ℝ; f(x) = (x+2), g(x) = (x2+3x+7), (f - g)(x) = f(x) - g(x) = (x+2) - (x2+3x+7) = -(x2 + 2x + 5), Domain: ℝ.

Scalar multiplication of a function: (kf)(x) = kf(x), ∀x∈ Domain(f). Domain(kf) = Domain(f). Examples: f(x) = sin(x), k = 2, 2sin(x), Domain: ℝ; ex, k = 3, 3ex, Domain: ℝ.

Product: (fg)(x) = f(x)g(x). Domain(f·g) = Domain(f) ∩ Domain(g). Examples: f(x) = x, g(x) = 2, (fg)(x) = 2x, Domain: ℝ;f(x) = (x+2), g(x) = (x2+3x+7), (fg)(x) = f(x)g(x) = (x+2)*(x2+3x+7) = x3 + 5·x2 + 13x + 14, Domain: ℝ.

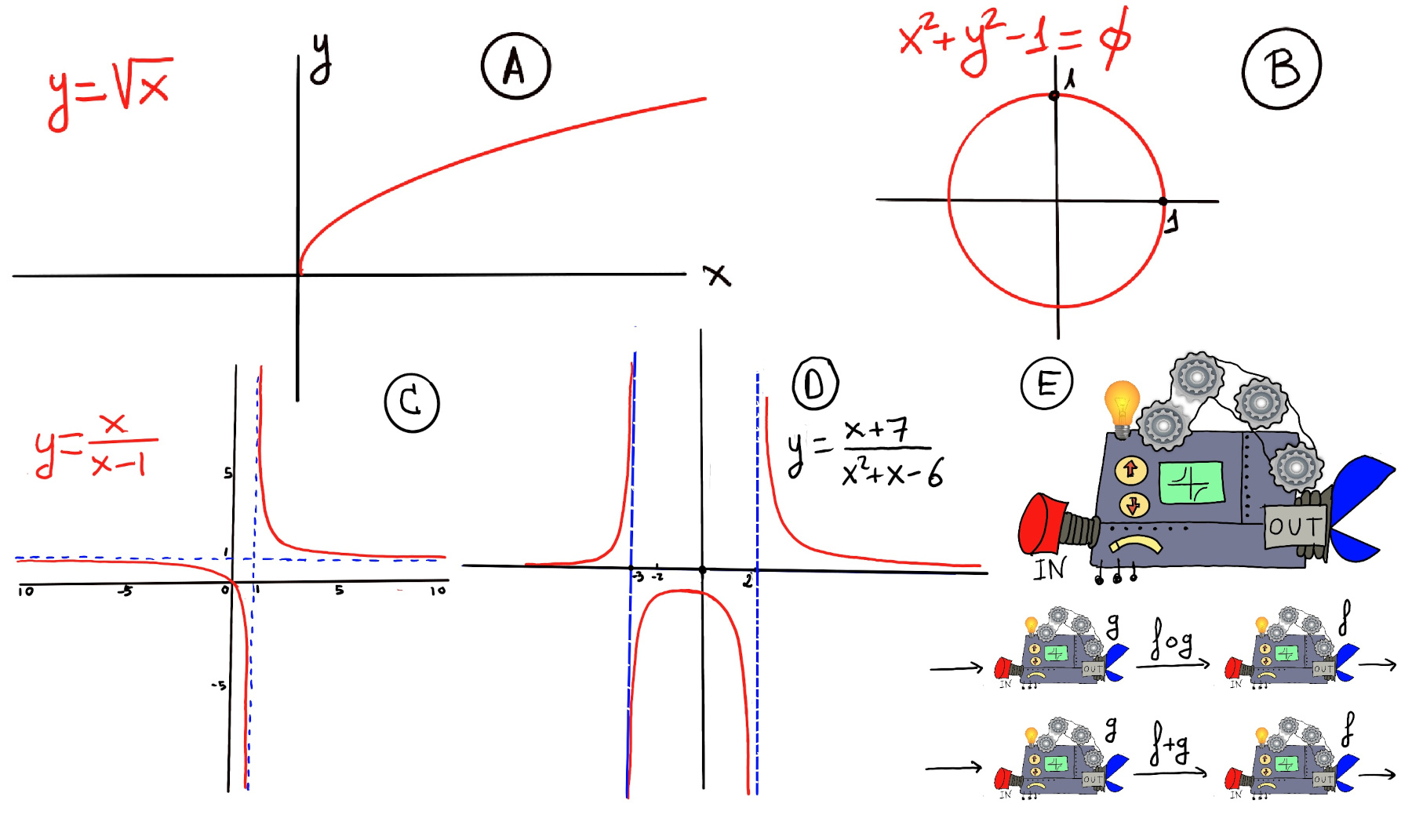

Division: (f/g)(x) = f(x)/g(x), Domain(f/g) = Domain(f) ∩ Domain(g) ∩ {x | g(x) ≠ 0}. We need to take extra care of including an additional condition so the denominator is not equal to zero because division by zero is undefined.Examples: f(x) = x, g(x) = x -1, $(\frac{f}{g})(x)=\frac{x}{x-1},$ (Figure C). f/g is obviously not defined at x = 1. $Domain(\frac{f}{g})= ℝ - \{ x| g(x) ≠ 0 \} = ℝ - \{ 1 \}$; f(x) = (x+7), g(x) = (x2+x-6), (f/g)(x) = f(x)/g(x) = $\frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6} = \frac{x+7}{(x-2)(x+3)}$ (Figure D). f/g is not defined at x = 2 and x = -3. $Domain(\frac{f}{g})= ℝ$ - {x| g(x) ≠ 0} = ℝ - {2, -3}.

Composition: (f∘g)(x) = f(g(x)). $Domain(f \circ g) = \{ x \in Domain(g) : g(x) \in Domain(f) \}$ In plain English: x must work for g AND $g(x)$ must work for f.

Imagine two machines on a factory assembly line. Machine g takes raw material x and produces intermediate product $g(x)$. Machine f takes that intermediate product and produces final output $f(g(x))$. The assembly line only works if: (1) The raw material x is compatible with Machine g. (2) The output $g(x)$ is compatible with Machine f.

Examples: $f(x) = \sqrt{x}$ (domain: $[0, \infty)$), $g(x) = x - 2$ (domain: ℝ), $(f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x)) = \sqrt{x - 2}$, $Domain(f \circ g) = [2, \infty)$ (x must be in Domain(g) = ℝ, g(x) = x -2 must be in the domain of f, $x -2 \geq 0$); $f(x) = \frac{1}{x}$ (domain: ℝ \ {0}), $g(x) = x^2 - 4$ (domain: ℝ), $(f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x)) = \frac{1}{x^2 - 4}$, $Domain(f \circ g)$ = ℝ \ {-2, 2}; $f(x) = \sqrt{x}$ (domain: $[0, \infty)$), $g(x) = x + 1$ (domain: ℝ), $(f \circ g)(x) = \sqrt{x + 1}$ (domain: $[-1, \infty)$), but $(g \circ f)(x) = \sqrt{x} + 1$ (domain: $[0, \infty)$). $f \circ g \neq g \circ f$ in general! The order matters enormously.

If f and g are differentiable where defined, the usual derivative rules apply.

So $(\frac{f}{g})' \lt 0, \forall x \ne 1$, $\frac{f}{g}$ is strictly decreasing on each interval of its domain.

For $h(x) = \frac{x}{x-1}$. $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{x}{x-1} = 1, \lim_{x \to -∞} \frac{x}{x-1} = 1$. The function has a horizontal asymptote at y = 1 and a vertical asymptote at x = 1, where the function is undefined, because the function blows up there: $\lim_{x \to 1-} \frac{x}{x-1} = -∞, \lim_{x \to 1+} \frac{x}{x-1} = ∞$

You can justify the horizontal limit by dividing numerator/denominator by x, or by L’Hôpital’s rule: $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{x}{x-1} = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{1}{1} = 1$

For $f(x) = \frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6}$. $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6} =[\text{Since degree of denominator (2) is larger than numerator (1)}] 0, \lim_{x \to -∞} \frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6} = 0$. So y = 0 is the horizontal asymptote.

L’Hôpital’s rule: $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6} = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{1}{2x+1} = 0.$

Vertical asymptotes at the zeros of the denominator: x = −3 and x = 2. Near each asymptote the function changes sign to ±∞. $\lim_{x \to -3⁻} \frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6} = \lim_{x \to -3⁻} \frac{(x+7)}{(x-2)(x+3)} = ∞, \lim_{x \to -3⁺} \frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6} = \lim_{x \to -3⁺} \frac{(x+7)}{(x-2)(x+3)} = -∞$

$\lim_{x \to 2⁻} \frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6} = \lim_{x \to 2⁻} \frac{(x+7)}{(x-2)(x+3)} = -∞, \lim_{x \to 2⁺} \frac{x+7}{x^2+x-6} = \lim_{x \to 2⁺} \frac{(x+7)}{(x-2)(x+3)} = ∞$.

We use the test point method to determine the sign of a function in each interval defined by its critical points.

Denominator is always positive on the domain, so the sign of $(\frac{f}{g})'$ is the negative of the sign of (x + 13)(x + 1). Critical numerator zeros: x = -13 and x = -1. Denominator zeros (domain exclusions): x = -3 and x = 2.

The critical points include 2 and -3, but we can exclude those from our analysis because our function is not defined on them.

$(\frac{f}{g})' > 0, (\frac{f}{g})'$ increasing on the interval (-13, -1) and $(\frac{f}{g})' < 0, (\frac{f}{g})'$ decreasing in (-∞, -13) ∪ (-1, ∞).

For log(u) to be defined, we need u > 0 (argument must be positive). So we need $\frac{x+3}{x-4} \gt 0$. We use the test point method to determine the sign of $\frac{x+3}{x-4}$. The critical points occur where the expression equals zero or is undefined: x + 3 = 0 or x -4 = 0, that is, -3 and 4 respectively. These split the real line into three intervals: (−∞, −3) test point x = -4; (−3, 4) test point x = 0; (4, ∞) test point x = 5.

Therefore, the domain is (-∞, -3) ∪ (4, ∞).

When a limit is infinite, we say the function diverges to infinity; strictly speaking, the limit does not exist as a real number, but the notation $\lim_{x \to 4} f(x) = \infin$ precisely describes this behaviour.