|

|

|

“Beauty is so many things… and you are in all of them,” I said. “Wow! I thought that you were as romantic as a brick to the head or a nuclear bomb’s guts”, Susanne replied, Apocalypse, Anawim, #justothepoint.

“When bias narratives, misleading news without context, and blatant lies spread like wildfire, history needs to be rewritten and truth needs to be cancelled”, Anawim, #justothepoint.

$\int_\gamma \frac{1}{(z-a)^2} dz = 0$ for any simple closed curve $\gamma$ around a because it has a valid, single-valued antiderivative (primitive) in the punctured domain $\mathbb{C} \setminus \{a\}$.

Using the power rule for integration ($\int x^n dx = \frac{x^{n+1}}{n+1}$), we get: $F(z) = \frac{(z-a)^{-1}}{-1} = -\frac{1}{z-a}$, and this is a valid function in the punctured domain $\mathbb{C} \setminus \{a\}$. It gives a unique complex number and it does’t jump if you walk around “a”.

Now, we could apply the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus. If a function f has an antiderivative F everywhere on the curve $\gamma$, then: $\int_\gamma f(z) dz = F(end_point) - F(start_point)$. Since $\gamma$ is a closed curve, the start and end points are the same ($z_{start_point} = z_{end_point}$), hence: $\int_\gamma \frac{1}{(z-a)^2} dz = F(z_{start}) - F(z_{start}) = 0$

Next, consider two different paths, $\alpha$ and $\beta$, that both start at point P and end at point Q. $\gamma = \beta - \alpha$ represents the closed loop formed by going forward along $\beta$ (from P to Q) and then backward along $\alpha$ (from Q back to P).

Since the integral over the closed loop $\gamma$ is zero, then: $\int_\gamma f(z) dz = 0 \implies \int_\beta f(z) dz - \int_\alpha f(z) dz = 0 \implies \int_\beta f(z) dz = \int_\alpha f(z) dz$. Conclusion: Path independence: Since the integral around the closed loop is zero, the integral from P to Q doesn't depend on which path you take.

However, $g(z) = \frac{1}{z-a}$. Its antiderivative G(z) = ln(z -a). The complex logarithm is multi-valued, $\int_\gamma \frac{1}{z-a} dz = G(\text{end}) - G(\text{start}) = 2\pi i \neq 0$. Because the integral is not zero, no single-valued global antiderivative exists on the punctured disk.

Any function analytic in an annulus (ring) around a can be written as: $f(z) = \dots + \frac{a_{-2}}{(z-a)^2} + \frac{\mathbf{a_{-1}}}{(z-a)} + a_0 + a_1(z-a) + \dots$

When we integrate this series around a closed curve surrounding a, we integrate term by term.

Conclusion: The integral of the entire function depends only on that one specific coefficient, $a_{-1}$. $\int_{\gamma} f(z) dz = 2\pi i \cdot a_{-1}$ This coefficient $a_{-1}$ is called the Residue because the 1/z term creates a “residue” (non-zero integral), while terms like $1/x^2$ vanish. Furthermore, a function $f(z)$ has an antiderivative in the punctured neighborhood if and only if its residue $a_{-1}$ is zero.

Let f be analytic in a punctured neighborhood of a, $\mathbb{B'}(a; r)$. Suppose f has a pole of order m at a. This means f(a) is infinite, preventing us from directly using Taylor series to expand f, as this approach requires the function to be nice (“smooth”) and differentiable at a.

We create a helper or auxiliary function h(z) by multiplying f(z) by exactly enough powers of $(z-a)$ to cancel out the infinity, $h(z) = (z-a)^m f(z)$.

Recall that if f has a pole of order m at a, then by definition there exists a holomorphic function g near a such that $f(z)=\frac{g(z)}{(z-a)^m}, g(a) \ne 0$, so h(z) = g(z). Since g is holomorphic at a, the limit exists and equals the value of g at a.

In other words, if $f$ has a pole of order m, it behaves roughly like $\frac{1}{(z-a)^m}$. Multiplying by $(z-a)^m$ neutralizes or cancels the pole. $\lim_{z \to a} h(z) = g(a) = \text{Finite Non-Zero Number}$

Because this limit exists, $h(z) = (z-a)^m f(z)$ has a removable singularity at $a$. We “fill the hole” by defining $h(a)$ as that limit. Now, $h(z)$ is analytic everywhere in the disk $\mathbb{B}(a; r)$.

We define $h(z) = \begin{cases} (z-a)^mf(z), &z \in \mathbb{B'}(a; r)\\\\ \lim_{z \to a}(z-a)^{m}f(z), &z = a \end{cases}$

Since h(z) is analytic at a, we can use Taylor’s Theorem to expand it into a power series with non-negative powers: $h(z) = c_0 + c_1(z -a) + c_2(z -a)^2 + \cdots + c_{m-1}(z -a)^{m-1}+ c_m(z -a)^m + \cdots, \forall z \in \mathbb{B}(a; r)$ where $c_0 = h(a) \ne 0$ (This confirms the pole was exactly order $m$) and the coefficients $c_n$ are just standard Taylor coefficients for h: $c_n = \frac{h^{(n)}(a)}{n!}$.

In particular for $z \ne a, (z-a)^mf(z) = c_0 + c_1(z -a) + c_2(z -a)^2 + \cdots + c_{m-1}(z -a)^{m-1}+ c_m(z -a)^m + \cdots, \forall z \in \mathbb{B'}(a; r)$. Obviously, we want $f(z)$, not $h(z)$, so we divide the entire Taylor series by $(z-a)^m$.

We have split f(z) into two distinct parts: $f(z) = \underbrace{\left[ \frac{c_0}{(z-a)^m} + \dots + \frac{c_{m-1}}{z-a} \right]}_{\text{Principal (Singular) Part}} + \underbrace{\left[ c_m + c_{m+1}(z-a) + \dots \right]}_{\text{Analytic (Regular) Part } f_1(z)}$

This is the Laurent Expansion. The first bracket contains all the negative powers (the “bad” and “naughty” part that causes the problem aka singularity), and the second bracket is a normal power series (the “good” and “nice” part).

Power series (like our $f_1(z)$) and Laurent series converge uniformly on any closed subset of their domain (like the contour $\gamma$). In analysis, uniform convergence is the “safety pass” that allows us to swap the limit (the infinite sum $\Sigma$) and the integral ($\int$), $\int_\gamma \left( \sum c_n (z-a)^n \right) dz = \sum c_n \left( \int_\gamma (z-a)^n dz \right)$

If $\gamma$ is a simple closed contour in $\mathbb{B'}(a; r)$ oriented positively such that $a \in Int(\gamma)$, $\int_{\gamma} f(z) dz =[\text{Sum of integrals of individual terms}] \int_{\gamma} \frac{c_0}{(z-a)^m} + \int_{\gamma}\frac{c_1}{(z-a)^{m-1}} + \cdots + \int_{\gamma} \frac{c_{m-1}}{z-a} + \int_{\gamma} f_1(z) = \int_{\gamma} \frac{c_{m-1}}{z-a} = c_{m-1}\cdot (2\pi i)$

Let’s look at the integral of a general term $\int_\gamma C (z-a)^k dz$. The function $(z-a)^k$ has a valid antiderivative: $F(z) = \frac{(z-a)^{k+1}}{k+1}$. We can apply the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

If a function f has an antiderivative F everywhere on the curve $\gamma$, then: $\int_\gamma f(z)dz=F(\text{end point})-F(\text{start point})$. Since the path $\gamma$ is closed, the integral is: $F(\text{end point}) - F(\text{start point}) = 0$. Every term in the series vanishes, except k = 1.

In conclusion, when one integrates the infinite series for f(z), the majority of the terms evaluate to zero, and only one single term survives. $\int_\gamma f(z) dz = 2\pi i \cdot c_{m-1}$. This coefficient $c_{m-1}$ is called the Residue of f at a, often denoted as $\text{Res}(f, a)$.

Lemma. Let f be analytic on and inside a positively oriented simple closed curve $\gamma$ except at a point a inside $\gamma$ where f has a pole of order m. Then, $\int_{\gamma}f(z)dz = c_{m-1}\cdot (2\pi i)$ where $c_{m-1}$ is the coefficient of $\frac{1}{z-a}$ in the singular part of the expansion of f as powers of (z -a) in the neighborhood of a.

Consider the Taylor series expansion of $\frac{1}{1-z}$ around 0, $\frac{1}{1-z} = \sum_{n=0}^\infty z^n$ and this geometric series only converges if the ratio |z| < 1. f(z) = $\frac{1}{1-z}$ has a singularity (has a pole) at z = 1. In words, the function explodes at z = 1.

Taylor Series are like local scanners. They sit at a center point (say, z = 0) and describe the function perfectly as you move outward. However, they have a major weakness. They cannot see past the first singularity. It is like expanding a ballon centered at 0. It grows until it hits the “sharp pin” (a wall or point of resistance) at z = 1. The moment it touches the pin, the balloon pops. The Taylor series is valid only inside that balloon (the disk $|z| < 1$).

What if we want to describe the function outside the balloon and “break the wall”, where $|z| > 1$? The standard formula $\sum z^n$ blows up to infinity there. We need a different approach.

We rewrite the function to force a geometric series that converges for large z. We do this by factoring out the “dominant” term (if |z| > 1, z is dominant): $\frac{1}{1-z} = \frac{-1}{z}\bigr( \frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{z}} \bigl)$. Since we are in the region |z| > 1, the reciprocal (our new ratio) is small, $|\frac{1}{z}| \lt 1$ and we can expand $\frac{1}{1 - (1/z)}$. This is obviously valid for |z| > 1: $\frac{1}{1-z} = \frac{-1}{z}\bigr( \sum_{n=0}^\infty (\frac{1}{z})^n \bigl) = -\sum_{n=0}^\infty z^{-n-1} =[\text{Reindexing}] -\sum_{n=-\infty}^{-1} z^m = - \left( \frac{1}{z} + \frac{1}{z^2} + \frac{1}{z^3} + \dots \right) = -z^{-1} - z^{-2} - z^{-3} - \dots$ for |z| > 1.

We have effectively characterized the behavior beyond the singularity! The cost is that we now use negative powers of z.

We often deal with functions having multiple singularities, e.g., $\frac{3}{(1-z)(4-z)}$. It has two singularities, specifically z = 1 and z = 4.

This splits the complex plane into three distinct regions: (i) the Core, $|z| < 1$ (inside both); (ii) the Annulus or donut region, $1 < |z| < 4$ (outside the first, inside the second); and (iii) the Exterior: $|z| > 4$ (outside both).

We want to find the expansion for the Annulus ($1 < |z| < 4$). We decompose the function using Partial Fractions: $f(z) = \underbrace{\frac{1}{1-z}}_{\text{Term 1}} - \underbrace{\frac{1}{4-z}}_{\text{Term 2}}$

Analyze Term 1. When |z| > 1, we have previously demonstrated that $\frac{1}{1-z} = -\sum_{n=-\infty}^{-1} z^m$. Analyze term 2. Likewise, when |z| < 4, $\frac{1}{4-z} =[\text{Factor out 4 to get the ratio z/4 < 1}] \frac{1}{4}\bigr( \frac{1}{1-\frac{z}{4}} \bigl) =[\text{Use standard Taylor series}] \frac{1}{4} \bigr( \sum_{n=0}^\infty (\frac{z}{4})^n \bigl)$.

So combining both results, when 1 < |z| < 4, $f(z) = \underbrace{-\sum_{n=-\infty}^{-1} z^n}_{\text{Negative Powers}} - \underbrace{\frac{1}{4}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \left(\frac{z}{4}\right)^n}_{\text{Positive Powers}}$ and both individually converge, so combine them together they converge in the common “annular” region 1 < |z| < 4. A Laurent Series is simply the combination of these two parts, a Principal Part (negative powers) to handle the inner hole, and an Analytic Part (positive powers) to handle the outer boundary.

Consider $g(x) = \frac{1}{1+x^2}$ on the real number line. The function looks perfectly normal, it is smooth everywhere. It’s a nice “hill” shape. It never goes to infinity for any real number x, and yet, if you try to build a Taylor series at x = 0, it fails to converge if $|x| \ge 1$. Why does it stop at 1 if there is no visible “bump” in the road?

The radius of convergence of a Taylor series about a equals the distance from a to the nearest singularity in the complex plane, even if you are only working with real numbers.

Complex analysis reveals the “invisible” obstacles. $1 + z^2 = 0 \implies z^2 = -1 \implies z = i, -i$. There are singularities (simple poles) at $i$ and $-i$. Even though these points are not on the real line, they are exactly distance 1 away from the origin, $|i-0|=1, |-i-0|=1.$ So the nearest singularity is exactly 1 unit away. Therefore, the Taylor series at 0 must have radius of convergence 1.

This is the Taylor series expansion of $\frac{1}{1+z^2}$ around 0, $\frac{1}{1+z^2} = \sum_{n=0}^\infty (-1)^nz^{2n}$ and this is valid for |z| < 1. The Taylor series “balloon” centered at 0 expands until it hits these imaginary obstacles at radius R = 1.

Double edged series (also called a two‑sided infinite series) is a formal sum indexed over all integers: $\sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty a_n$. Unlike ordinary series, this one extends infinitely in both directions.

Because this series extends infinitely in both directions, there is no natural notion of partial sums like in a one‑sided series. To give it a well‑defined meaning, we interpret it by splitting it into its positive and negative parts. We say that the two-sided series $\sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty a_n$ converges if and only if both of the following one-sided series converge in the usual sense, $\sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n, \sum_{n=1}^\infty a_{-n}$. When this happens, we define the value of the two-sided series to be $\sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty a_n = s_1 + s_2$ where $s_1 = \sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n$ and $s_2 = \sum_{n=1}^\infty a_{-n}$

Laurent’s theorem. Let A = {$z \in \mathbb{C}: R \lt |z -a| \lt S$} be an annular region ($0 \le R \lt S \le \infty$) and let f be analytic on A. Then, $f(z) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty c_n(z -a)^n, \forall z \in A$ where $c_n = \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma} \frac{f(w)}{(w-a)^{n+1}}dw$ and $\gamma$ is a positively oriented circle of radius r centered at a and R < r < S ($\gamma$ is inside the annular region).

Proof.

The theorem is true for any center point a. However, carrying the term $(z-a)$ through every single line of algebra is messy, confusing, and indeed quite tiring. Let’s just assume a is at the origin. If we prove it for 0, we can just shift (by a translation) the entire universe back to a at the end by replacing every z with $(z-a)$.

The Annulus is now $R < |z| < S$, i.e., a donut shape defined by an inner radius R and an outer radius S. We pick a specific point z inside this donut and sandwich it between two arbitrary circles: (i) inner Circle ($C_P$), radius P; (ii) and outer Circle ($C_Q$), radius Q, so R < P < |z| < Q < S.

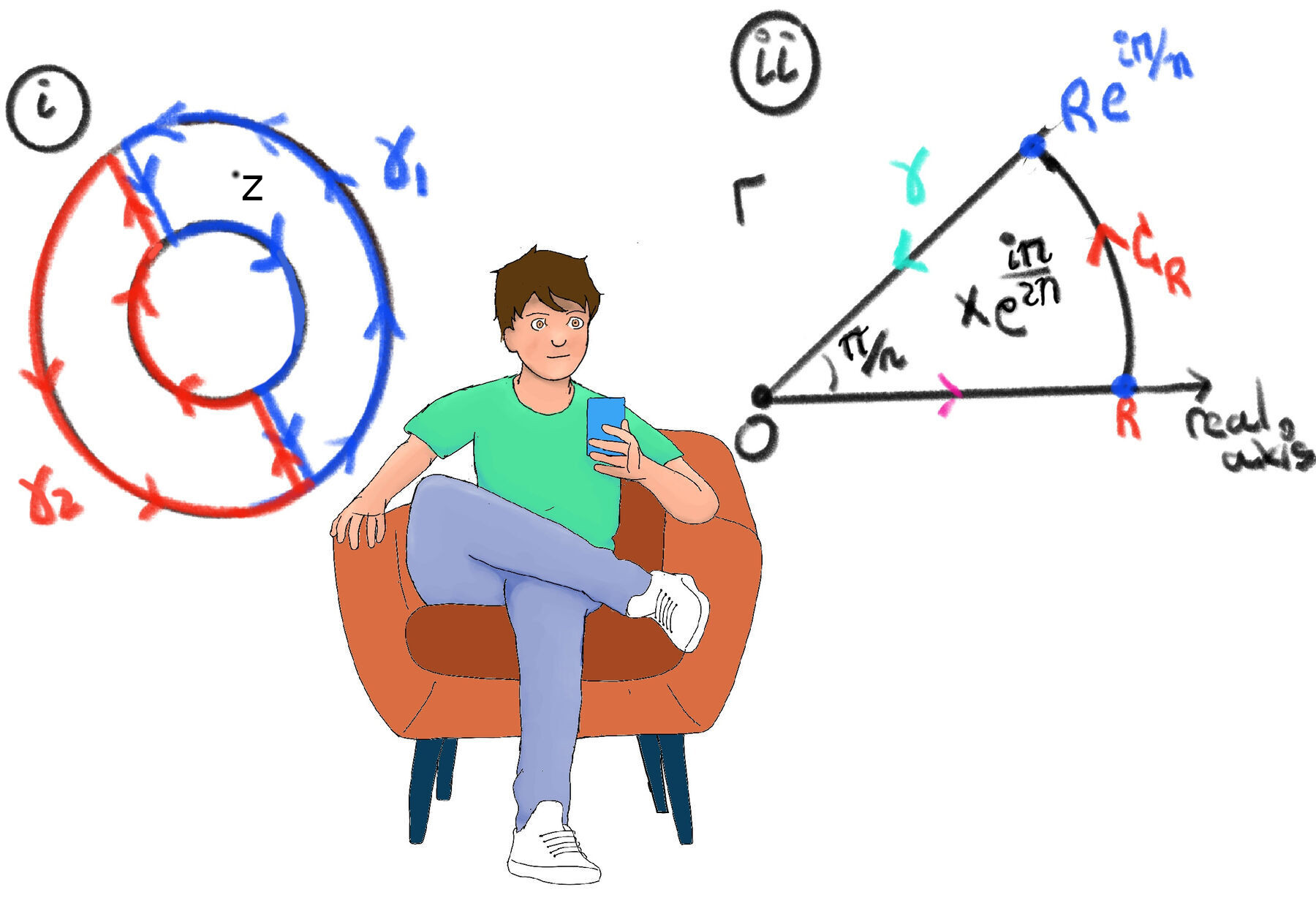

💡 We cannot simply integrate around the whole donut because the hole in the middle (where the function might blow up) prevents us from using Cauchy’s Formula directly, so we cut the donut in half with two “C-shaped” curves (Figure i):

Now we apply Cauchy’s Integral Formula and Cauchy’s Theorem.

$f(z) =[\text{Cauchy's Integral Formula}] \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma_1}\frac{f(w)}{w-z}dw$ since f is analytic inside and on $\gamma_1$ (a simple closed curve) and $z \in Int(\gamma_1)$ (inside this closed loop)

$0 =[\text{Cauchy's Theorem}] \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma_2}\frac{f(w)}{w-z}dw$ since $\frac{f(w)}{w-z}$ is analytic on and inside $\gamma_2$, meaning for $w \in Int(\gamma_2)$ and $w \in \gamma_2^*$, the integral is zero.

Combining both results, $f(z) + 0 = f(z) = \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma_1}\frac{f(w)}{w-z}dw + \int_{\gamma_2}\frac{f(w)}{w-z}dw = \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma_1 + \gamma_2}\frac{f(w)}{w-z}dw = \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{C_Q}\frac{f(w)}{w-z}dw - \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{C_P}\frac{f(w)}{w-z}dw$ where $C_Q$ is a (outer) circle of radius Q oriented positively and $C_R$ is a (inner) circle of radius R oriented positively, too.

When we add the paths $\gamma_1 + \gamma_2$, the “cuts” (the vertical lines that go through the ring) are traversed twice in opposite directions, effectively cancelling each other out. As a result, only the outer circle $C_Q$ (which is traversed counter-clockwise $\circlearrowleft$) and the inner circle $C_P$ (which is traversed clockwise $\circlearrowright$, so we flip it and add a minus) are left.

The Outer Integral ($C_Q$). $w$ is on the outer circle and $z$ is inside. So $|w| > |z|$. We want a ratio smaller than 1 to use the Geometric Series formula $\frac{1}{1-r} = \sum r^n$. We choose $r = \frac{z}{w}$.

$w \in C_Q \implies \frac{1}{w-z} = \frac{1}{w(1-\frac{z}{w})} [\text{Expand with geometric series}] \frac{1}{w}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (\frac{z}{w})^n = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{z^n}{w^{n+1}}$.

Substitute this into the integral: $\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{C_Q} f(w) \left( \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{z^n}{w^{n+1}} \right) dw = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \left( \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{C_Q} \frac{f(w)}{w^{n+1}} dw \right) z^n$. This gives the Positive Powers, $n=0, 1, 2 \dots$.

Why have we been able to swap sum and integrals? We are allowed to do this because the series converges uniformly. Recall that we expanded $\frac{1}{w-z}$ using a Geometric Series: $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \left(\frac{z}{w}\right)^n$. This series converges if the ratio $|r| < 1$.

On the Outer Circle ($C_Q$): The variable of integration $w$ is on the circle of radius $Q$. The fixed point z is inside, so |z| < Q, and the ratio is $|\frac{z}{w}| = \frac{|z|}{Q} < 1$. The Weierstrass M-Test states that if the ratio is bounded by a constant strictly less than 1 for all w on the integration path, the series converges uniformly.

The Inner Integral ($C_P$). Here, w is on the inner circle and z is outside it. So $|z| > |w|$. We need a ratio smaller than 1. We must choose $r = \frac{w}{z}$.

$\frac{1}{w-z} = \frac{-1}{z-w} = \frac{-1}{z(1 - \frac{w}{z})} = -\frac{1}{z} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \left(\frac{w}{z}\right)^k = -\sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{w^k}{z^{k+1}}$

Substitute this into the integral. Be careful, the integral had a minus sign in front of it and the series expansion also has a minus sign, so they cancel out to become positive.

$+ \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{C_P} f(w) \left( \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{w^k}{z^{k+1}} \right) dw = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \left( \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{C_P} f(w) w^k dw \right) \frac{1}{z^{k+1}}$

We have a sum of terms looking like $\frac{1}{z^{k+1}}$. We want to make this look like $z^n$ where $n$ is negative. Let $n = -(k+1) \implies n = - k - 1 \implies k = -n -1$. (i) If k = 0, then n = -1; (ii) If k = 1, then n = -2; (iii) The power $w^k$ inside the integral becomes $w^{-n-1}$; (iv) and the term $z^{-(k+1)}$ becomes $z^n$.

This transforms the second sum into: $\sum_{n=-\infty}^{-1} \left( \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{C_P} \frac{f(w)}{w^{n+1}} dw \right) z^n$

Since $f$ is analytic in the ring or annulus, Cauchy’s Deformation Theorem says the integrals over $C_Q$ and $C_P$ are actually the same as the integral over any curve $\gamma$ strictly between them (Note 1). So we can just call the path $\gamma$.

$f(z) = \underbrace{\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} c_n z^n}_{\text{Outer Part}} + \underbrace{\sum_{n=-\infty}^{-1} c_n z^n}_{\text{Inner Part}} = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} c_n z^n$ where $c_n = \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_\gamma \frac{f(w)}{w^{n+1}} dw$

Note 1. The function we are integrating to find the coefficients $c_n$ is: $g(w) = \frac{f(w)}{w^{n+1}}$

Uniqueness of Laurent’s expansion. Let f be analytic in A = $\{ z \in \mathbb{C}: R \lt |z - a| \lt S \}(0 \le R \lt S \le \infty)$ and suppose $f(z) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} d_n (z-a)^n (z \in A)$. Then, $d_n = \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_\gamma \frac{f(w)}{(w-a)^{n+1}} dw, \forall n \in \mathbb{Z}$

The goal of this proof is to answer a quite simple question. If I find a series that equals or represents f(z), is it the Laurent series? The answer is a definitive yes. You cannot obtain a different series expansion for the same function in the same annulus.

Proof.

We already know (from Laurent’s Theorem) that there exists a series with specific coefficients determined by integrals. Let’s call those “official” coefficients $c_n$.

Now, suppose you found a series representation with some coefficients $d_n, f(z) = \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} d_k (z-a)^k$. We assume this series converges to f(z) everywhere in the annulus A.

We choose a circle $C_r$ of radius $r$ inside the annulus ($R < r < S$) to integrate over.

We want to isolate a specific coefficient, say $d_n$.

$$ \begin{aligned} 2\pi i c_n &=[\text{Laurent’s theorem}] \int_{C_r} \frac{f(w)}{(w-a)^{n+1}}dw \\[2pt] &[\text{We substitute the series expansion into the integral formula:}]\\[2pt] &=\int_{C_r} \bigr( \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} d_k (w-a)^k \bigl)\frac{1}{(w-a)^{n+1}}dw \\[2pt] &[\text{Bring the denominator } (w-a)^{n+1} \text{ inside the sum.}] \\[2pt] &=\int_{C_r} \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} d_k (w-a)^{k-n-1} dw \\[2pt] &[\text{Because a Laurent series converges uniformly on any closed circle strictly inside the annulus (like our $C_r$), we are legally allowed to swap the infinite sum ($\sum$) and the integral ($\int$).}] \\[2pt] &=\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} d_k \left( \int_{C_r} (w-a)^{k - n - 1} dw \right) \end{aligned} $$The filter mechanism. Now we analyze the integral inside the parenthesis, $\int_{C_r} (w-a)^{k - n - 1} dw$. We know from basic complex integration that the integral of a power function $\int (w-a)^{exponent} dw$ around a closed loop around the origin follows a strict binary rule:

$exponent = - 1 \implies k - n - 1 = -1 \implies k - n = 0 \implies k = n$ and $\text{Integral} = \dots + d_{n-1}(0) + d_n(2\pi i) + d_{n+1}(0) + \dots$

Then, $2\pi i c_n = d_n(2\pi i) \implies c_n = d_n$