|

|

|

It ain’t about how hard you can hit. Its about how hard you can get hit, and how much you can take, and keep moving forward, Rocky Balboa

Laurent’s theorem. Let A = {$z \in \mathbb{C}: R \lt |z -a| \lt S$} be an annular region ($0 \le R \lt S \le \infty$) and let f be analytic on A. Then, $f(z) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty c_n(z -a)^n, \forall z \in A$ where $c_n = \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma} \frac{f(w)}{(w-a)^{n+1}}dw$ and $\gamma$ is a positively oriented circle of radius r centered at a and R < r < S ($\gamma$ is inside the annular region).

Corollary (aka Rosetta Stone of Complex Analysis). Let f be analytic in $\mathbb{B'}(a; r)$. (i) f has a removable singularity at a if and only if in the Laurent's series expansion of f around a ($\sum_{n = -\infty}^\infty (z-a)^n$) all negative coefficients are zero $c_n = 0, \forall n \lt 0$. (ii) f has a pole of order m ($m \ge 1$) at a if and only if the series stop at the negative power -m, $c_{-m} \ne 0, c_n = 0, \forall n \lt -m$; (iii) f has an isolated essential singularity at a if and only if the series has infinitely many negative terms (it never stops), i.e., there is no m such that $c_n = 0, \forall n \lt -m$

The Argument Principle. Suppose f is meromorphic on and inside a simple closed curve $\gamma$ with a finite number of zeroes $a_j, 1 \le j \le l_1$ and poles $b_k, 1 \le k \le l_2$. Suppose none of those zeros and poles lie on $\gamma$. Then, $\frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{\gamma}\frac{f'(z)}{f(z)}dz = M - N$ where M is the sum of order of zeroes at $a_j, 1 \le j \le l_1$ and N is the sum of order of poles at $b_k, 1 \le k \le l_2$

We want to calculate the improper real integral: $\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{dx}{1+x^{2n}}, \forall n \in \mathbb{N}, n \gt 1$. We cannot compute this directly using standard Calculus.

Inspired by this integral, we extend the integrand to the complex plane $\frac{1}{1+z^{2n}}$.

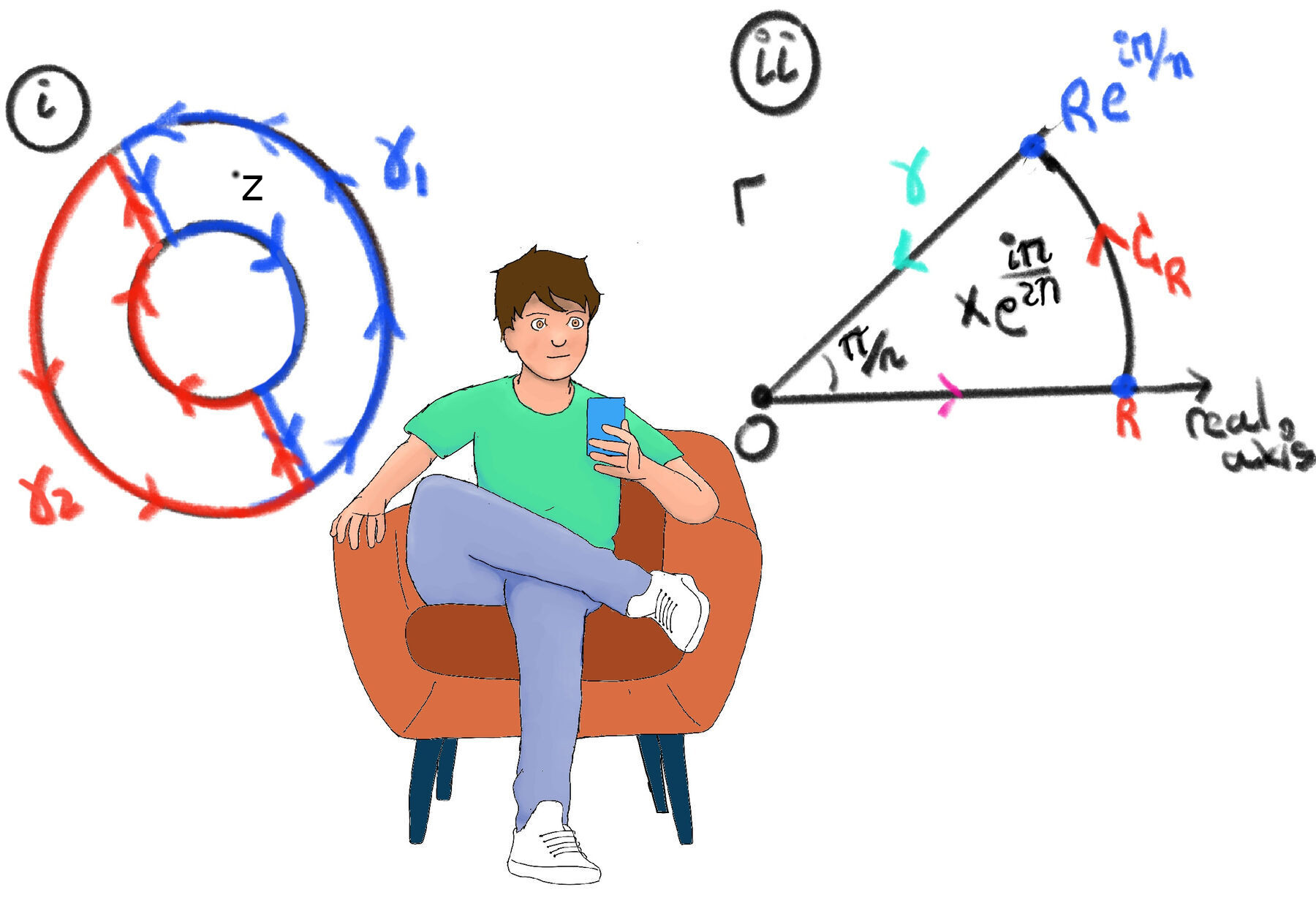

We choose a contour $\Gamma$ that consists of three paths (a “pizza slice”, Figure ii):

Why this specific angle $\pi/n$? Because the function depends on $z^{2n}$. If we rotate $z$ by an angle of $\pi/n$, then $z^{2n}$ rotates by $2n(\pi/n) = 2\pi$, which brings us back to where we started. This symmetry is absolutely essential for the algebra later.

We want to integrate $\frac{1}{1+z^{2n}}$ around our “Pizza Slice” shape (sector) in the complex plane. We need to find the singularities inside our pizza slice. Singularities occur when the denominator is zero: $1 + z^{2n} = 0 \implies z^{2n} = -1$. In polar form, $-1 = e^{i\pi}, e^{3i\pi}, e^{5i\pi}, \dots$. In polar form, all representations of -1 are $-1=e^{i(\pi +2\pi m)}, m\in \mathbb{Z}$. So, we solve $z^{2n}=e^{i(\pi +2\pi m)}$, the 2n distinct roots are: $z_k = e^{i\frac{(2k+1)\pi}{2n}}, k = 0, 1, 2, \cdots, 2n-1$.

Which one is inside our “pizza” 🍕 slice? Our slice goes from angle $0$ to $\frac{\pi}{n}$ (or $\frac{2\pi}{2n}$).

By Cauchy Residue Theorem, $\int_{\Gamma} \frac{1}{1+z^{2n} }dz= 2\pi i \cdot Res\{ \frac{1}{1+z^{2n}}; e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}} \}$

$\lim_{z \to e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}} (z - e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}) \frac{1}{1+z^{2n}} =[\text{For simplicity, let's name }a = e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}] \lim_{z \to a} \frac{1}{\frac{1+z^{2n}-0}{z-a}}$

Recall the concept of derivative $g'(a) = \lim_{z \to a}\frac{g(z)-g(a)}{z-a}$ where $g(z) = 1 + z^{2n}, g (a) = 0$

We need the residue at $a = e^{i\frac{\pi}{2n}}$.Since it is a simple pole, we use the derivative formula: $\text{Res}(f, a) = \frac{1}{g'(a)} \quad \text{where } g(z) = 1+z^{2n}$

$lim_{z \to a} \frac{1}{\frac{1+z^{2n}-0}{z-a}} = \frac{1}{(1+z^{2n})'|_{e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}}} = \frac{1}{2nz^{2n-1}|_{e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}}} = \frac{1}{2n(e^{i\pi}e^{\frac{-i\pi}{2n}})} = \frac{e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}}{-2n} =\frac{-e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}}{2n}$

$2\pi iRes\{ \frac{1}{1+z^{2n}}; e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}} \} = 2\pi i( \frac{-e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}}{2n}) = \frac{-i\pi e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}}{n}$

Now we break the loop into its three parts: $\int_{\Gamma} \frac{1}{1+z^{2n}}dz = \int_{0}^{R}\frac{1}{1+x^{2n}}dx + \int_{C_R}\frac{1}{1+z^{2n}}dz + \int_{\gamma}\frac{1}{1+z^{2n}}dz$.

$z = r e^{i\frac{\pi}{n}} \implies dz = e^{i\frac{\pi}{n}} dr$. Then, $1 + z^{2n} = 1 + (r e^{i\frac{\pi}{n}})^{2n} = 1 + r^{2n} e^{i 2\pi} = 1 + r^{2n}$ (The avid reader should not fail to notice how the complex part has completely vanished! This is why we chose this angle and “pizza slice”).

$\int_{\gamma} \frac{dz}{1+z^{2n}} = \int_{R}^{0} \frac{e^{\frac{i\pi}{n}}dr}{1+ (re^{\frac{i\pi}{n}})^{2n}} = -e^{\frac{i\pi}{n}}\int_{0}^{R} \frac{dr}{1+r^{2n}}$ Letting $R \to \infty$, this becomes $-e^{\frac{i\pi}{n}}\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{dx}{1+x^{2n}} = - e^{i\frac{\pi}{n}} \cdot I$.

L.H.S. = $(1 -e^{\frac{i\pi}{n}})I = (1 -e^{\frac{i\pi}{n}})\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{dx}{1+x^{2n}}$

R.H.S. = $\frac{-i\pi e^{\frac{i\pi}{2n}}}{n}$

Combining both results: $I = \frac{-\frac{i \pi}{n} e^{i\frac{\pi}{2n}}}{1 - e^{i\frac{\pi}{n}}}$

Multiply the numerator and denominator by $e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2n}}$: $I = \frac{-\frac{i \pi}{n} e^{i\frac{\pi}{2n}} \cdot e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2n}}}{(1 - e^{i\frac{\pi}{n}}) \cdot e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2n}}} = \frac{-\frac{i \pi}{n}}{e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2n}} - e^{i\frac{\pi}{2n}}}$

Swap the sign in the denominator to make it look like sine definition ($e^{ix} - e^{-ix}$), recall $\sin(\theta) = \frac{e^{i\theta} - e^{-i\theta}}{2i} \implies e^{i\theta} - e^{-i\theta} = 2i \sin(\theta)$: $I = \frac{-\frac{i \pi}{n}}{-(e^{i\frac{\pi}{2n}} - e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2n}})} = \frac{\frac{i \pi}{n}}{e^{i\frac{\pi}{2n}} - e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2n}}}= \frac{i \pi / n}{2i \sin(\frac{\pi}{2n})} = \frac{\pi}{2n \sin(\frac{\pi}{2n})}$

$\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{dx}{1+x^{2n}} = \boxed{\frac{\pi}{2n \sin(\frac{\pi}{2n})}}$

Use a residue and the following contour $\gamma_R$ to show that $\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{dx}{x^3+1} = \frac{2\pi}{3\sqrt{3}}$

Solution:

We want to calculate $I = \int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{dx}{x^3+1}$. We choose a “Pizza Slice” contour (sector) $\Gamma_R$ in the complex plane to exploit the symmetry of $z^3$.

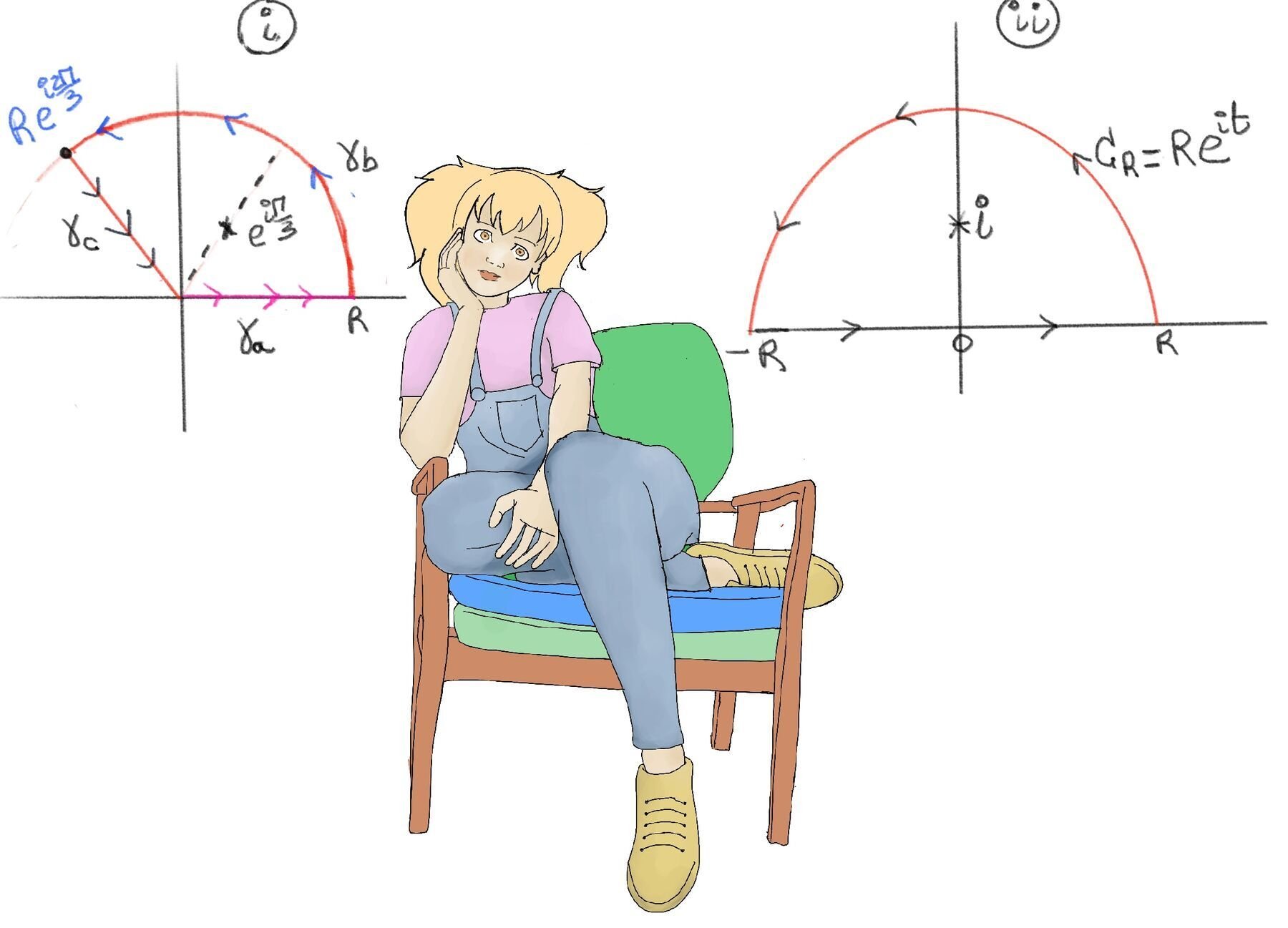

$\gamma$ can be sliced into three parts as follows (Figure i):

Inspired by the integrand of the problem, we define the complex function $f(z) = \frac{1}{z^3+1}$. We need to calculate the roots of $z^3 + 1 = 0 \implies z^3 = -1$. In polar form, $-1 = e^{i\pi}$.

The roots are separated by $2\pi/3: z = e^{\frac{2n\pi + \pi}{3}i}$ for n = 0, 1, and 2. $z_0 = e^{\frac{i\pi}{3}}$ (n = 0, Angle $60^\circ$), $z_1 = e^{i3\pi/3} = e^{i\pi} = -1$ (n = 1, Angle $180^\circ$), and $z_2 = e^{i5\pi/3}$ (n = 2, Angle $300^\circ$).

Our slice goes from $0^\circ$ to $120^\circ$ ($2\pi/3$), therefore only $z_0 = e^{i\pi/3}$ lies inside the contour.

The residue at a simple pole $z_0$ for $f(z) = 1/g(z)$ is the derivative formula: $\text{Res} = 1/g'(z_0)$. In our particular case, $g(z) = z^3 + 1 \implies g'(z) = 3z^2$, and evaluated at $z_0 = e^{i\pi/3}$ gives $\text{Res}(f, e^{i\pi/3}) = \frac{1}{3(e^{i\pi/3})^2} = \frac{1}{3e^{i2\pi/3}} = \frac{e^{-i2\pi/3}}{3} = \frac{1}{3} \left( \cos\left(-\frac{2\pi}{3}\right) + i\sin\left(-\frac{2\pi}{3}\right) \right) = \frac{1}{3} \left( -\frac{1}{2} - i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \right)$

By Cauchy’s residue theorem, $\int_{\gamma_R} f(z)dz = 2\pi i Res(f, e^{\frac{i\pi}{3}})$ (*)

$\int_{\gamma_R} f(z)dz = \int_{\gamma_a} f(z)dz =\int_{\gamma_b} f(z)dz = \int_{\gamma_c} f(z)dz$

Analyzing the Three Paths:

Path $\gamma_a$ (Real Axis): $\int_0^R \frac{dx}{x^3+1} \to I \quad (\text{as } R \to \infty)$

Path $\gamma_b$ (The Arc): $\gamma_b(t) = Re^{it}, 0 \le t \le \frac{2\pi}{3}$. $z=Re^{it},\ dz=iRe^{it}dt, |dz|=Rdt$. $\int_{\gamma_b} f(z)dz = \int_{0}^{\frac{2\pi}{3}}\frac{Re^{it}idt}{R^3e^{i3t} + 1}$

Notice that $e^{3it}$ is a point in the unit circle, so $R^3e^{i3t}$ is in the circle of radius $R^3, |R^3e^{i3t} + 1| \ge[\text{Reverse triangle inequality} |z+w| ≥ ∣z∣−∣w|] R^3-1$. Hence, $\frac{1}{|R^3e^{i3t} + 1|} \le \frac{1}{R^3-1}$

$|\int_{0}^{\frac{2\pi}{3}}\frac{Re^{it}idt}{R^3e^{i3t} + 1}| \le R\int_{0}^{\frac{2\pi}{3}} \frac{|dt|}{|R^3e^{i3t} + 1|}$

$R\int_{0}^{\frac{2\pi}{3}} \frac{|dt|}{|R^3e^{i3t} + 1|} \le \frac{R}{R^3-1}\cdot \frac{2\pi}{3} = \frac{2\pi}{3}\frac{R}{R^3-1} \to 0 \text{ as } R \to \infty$

Path $\gamma_c$ (The Return Trip): We travel from $Re^{i2\pi/3}$ to $0$. Let parameterize it using $z = t e^{i2\pi/3}, R \ge t \ge 0$. $z^3 = (t e^{i2\pi/3})^3 = t^3 e^{i2\pi} = t^3, dz = e^{i2\pi/3} dt$

$\int_{\gamma_c} f(z)dz = \int_R^0 \frac{e^{\frac{2\pi}{3}}dt}{(e^{\frac{2\pi}{3}}t)^3+1} = - e^{i2\pi/3} \int_0^R \frac{dt}{t^3+1}$. As $R \to \infty$: $\int_{\gamma_c} f(z)dz \to - e^{i2\pi/3} I$

By Cauchy’s residue theorem (*): $I + 0 - e^{i2\pi/3} I = 2\pi i \left( \frac{1}{3e^{i2\pi/3}} \right)$

Factor out $I$: $I (1 - e^{i2\pi/3}) = \frac{2\pi i}{3e^{i2\pi/3}}$

Solve for $I$:

$$ \begin{aligned} I &=\frac{2\pi i}{3e^{i2\pi/3} (1 - e^{i2\pi/3})} \\[2pt] &= \frac{2\pi i}{3 (e^{i2\pi/3} - e^{i4\pi/3})}\\[2pt] &[\text{Use periodicity of the complex exponential: } e^{i4\pi/3} = e^{i4\pi/3 -2\pi} = e^{i4\pi/3 -6\pi/3} = e^{-i2\pi/3}] \\[2pt] &= \frac{2\pi i}{3(e^{i2\pi/3} - e^{-i2\pi/3})} \\[2pt] &[\text{Recall the identity: } e^{i\theta}-e^{-i\theta}=2i\sin(\theta)] \\[2pt] &= \frac{2\pi i}{3 (2i \sin(2\pi/3))} \\[2pt] &= \frac{\pi}{3 \sin(2\pi/3)} \\[2pt] &[\text{We know }] sin(\frac{2\pi}{3}) = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \\[2pt] &=\frac{\pi}{3 (\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2})} = \frac{2\pi}{3\sqrt{3}} \end{aligned} $$The reader should notice that the integrand, $f(x) = \frac{\cos(3x)}{(x^2+1)^2}$ is an even function.

$\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\cos(3x)}{(x^2+1)^2} =[\text{Improper integral definition}] \lim_{R_1 \to \infty} \int_{-R_1}^0 \frac{\cos(3x)}{(x^2+1)^2} + \lim_{R_2 \to \infty} \int_0^{R_2} \frac{\cos(3x)}{(x^2+1)^2}$

Define the complex function $f(z) := \frac{e^{i3z}}{(z^2+1)^2} = \frac{\cos(3z)}{(z^2+1)^2} + i \frac{\sin(3z)}{(z^2+1)^2}$.

Why not integrate just cos(3z)? If we put $\cos(3z)$ directly into the complex plane, it blows up (goes to infinity) along the imaginary axis because $\cos(iy) = \cosh(y)$. Instead, we use Euler’s formula: $e^{3ix} = \cos(3x) + i\sin(3x)$ and we will integrate the function $f(z) = \frac{e^{3iz}}{(z^2+1)^2}$

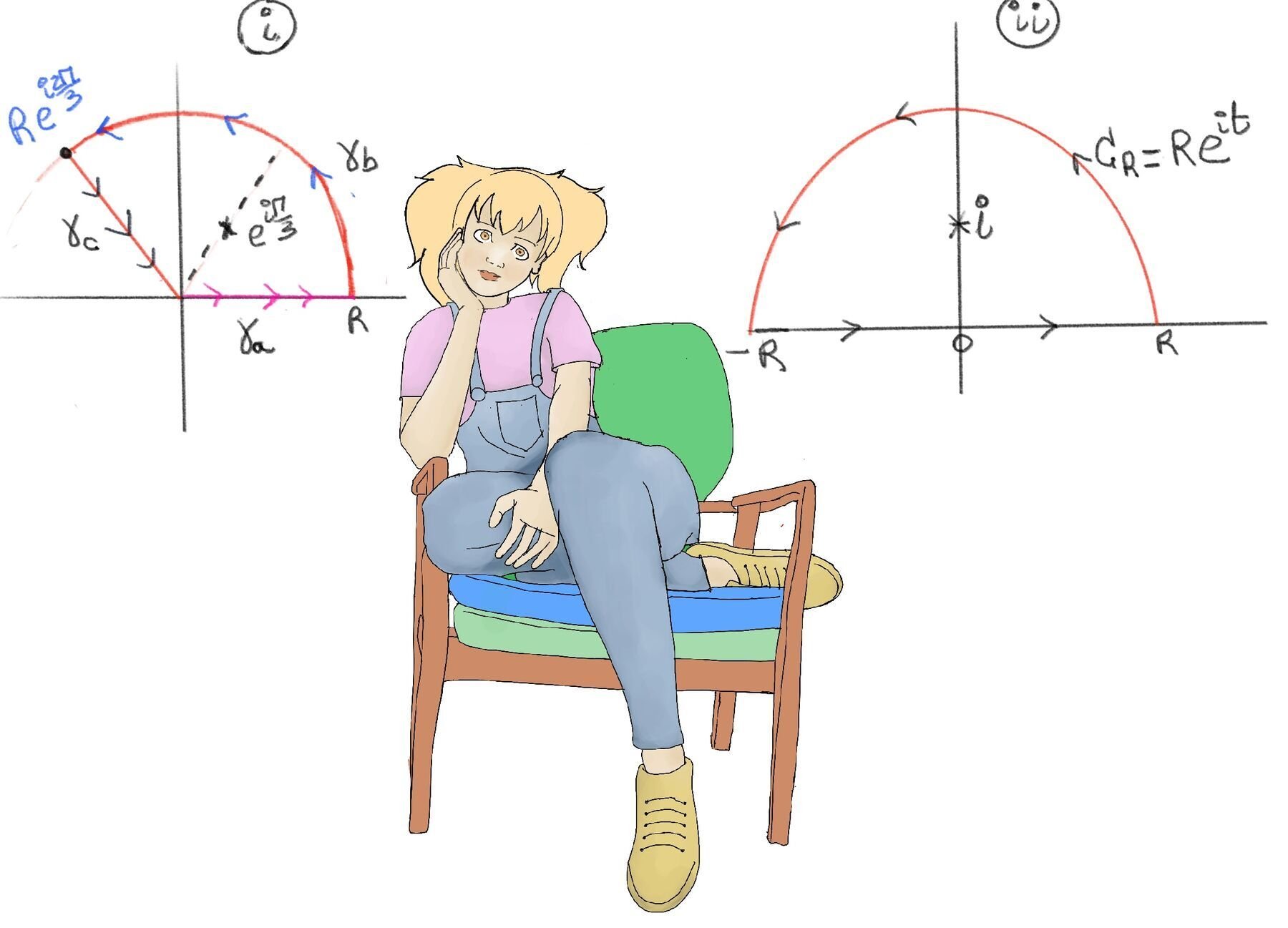

We integrate over a simple closed loop $\gamma$ consisting of two parts (Figure ii):

The denominator is $(z^2+1)^2 = 0$. Its roots are $z = i$ and $z = -i$. Since the denominator is squared, these are poles of order 2. Except in these poles, f is entire everywhere. Inside our upper semicircle contour, the only singularity is z = i.

By Cauchy’s residue theorem, $2\pi i Res(f; i) = \int_{\gamma + C_R} f(z)dz = \int_{\gamma} f(z)dz + \int_{C_R} f(z)dz$

For a pole of order 2 at $z_0$, the residue is: $\text{Res}(f, z_0) = \lim_{z \to z_0} \frac{d}{dz} \left[ (z-z_0)^2 f(z) \right]$

Multiply $f(z)$ by $(z-i)^2$ to remove the singularity: $\phi(z) = (z-i)^2 f(z) =[f(z) = \frac{e^{3iz}}{(z-i)^2(z+i)^2}] \frac{e^{3iz}}{(z+i)^2}$

We need $\phi'(z)$. Use the Quotient Rule $\left( \frac{u}{v} \right)' = \frac{u'v - uv'}{v^2}$, $u = e^{3iz} \implies u' = 3ie^{3iz}, v = (z+i)^2 \implies v' = 2(z+i)$, we get: $\phi'(z) = \frac{3ie^{3iz}(z+i)^2 - e^{3iz} \cdot 2(z+i)}{((z+i)^2)^2} =[\text{Factor out } e^{3iz}(z+i)] \frac{e^{3iz}(z+i) [ 3i(z+i) - 2 ]}{(z+i)^4} = \frac{e^{3iz} [ 3iz - 3 - 2 ]}{(z+i)^3} = \frac{e^{3iz} (3iz - 5)}{(z+i)^3}$

$Res(f, i) = \frac{e^{3iz} (3iz - 5)}{(z+i)^3}|_{z=i} = \frac{e^{3i(i)}(3i(i) - 5)}{(i + i)^3} = \frac{e^{-3} (-3 - 5)}{(2i)^3} = \frac{-8e^{-3}}{-8i} = \frac{ 8e^{-3}}{8i^3} = \frac{e^{-3}}{i} =\frac{-i}{e^3}$

Cauchy’s Residue Theorem, $\oint_\gamma f(z) dz = 2\pi i \left( \frac{-i}{e^3} \right) = \frac{2\pi (-i^2)}{e^3} = \frac{2\pi (1)}{e^3} = \frac{2\pi}{e^3}$

This gives us the value for the entire closed loop: $\int_{-R}^R f(x) dx + \int_{C_R} f(z) dz = \frac{2\pi}{e^3}$

The Arc Integral vanishes. $z = Re^{it}, dz = Rie^{it}dt, f(z) = \frac{e^{3iRe^{it}}}{(R^2e^{2it}+1)^2}$

The integral around $C_R$ is the following expression: $\int_{0}^\pi \frac{e^{3iRe^{it}}Rie^{it}dt}{(R^2e^{2it}+1)^2}$

Notice that $e^{2it}$ is a point in the unit circle, so $R^2e^{i2t}$ is in the circle of radius $R^2, |R^2e^{i2t} + 1| \ge[\text{Reverse triangle inequality} |z+w| ≥ ∣z∣−∣w|] R^2-1$. Hence, $\frac{1}{(R^2e^{i2t} + 1)^2} \le \frac{1}{(R^2-1)^2}$

$e^{it}=\cos(t) + i\sin(t) \implies 3iRe^{it}=3iR\cos(t) - 3R\sin(t)$. This expression is complex, with real part $- 3R\sin(t)$, the modulus is $|e^{3iRe^{it}}| = e^{-3Rsin(t)} \le e^0 = 1 \iff -3R\sin(t)\le 0 \text{ i.e., } R \sin(t) \ge 0$ and this holds because R > 0 and t∈ [0,π] (where sin(t) ≥ 0, we are in the upper half plane).

$|\int_{0}^\pi \frac{e^{3iRe^{it}}Rie^{it}dt}{(R^2e^{2it}+1)^2}| \le |\int_{0}^\pi \frac{1\cdot R \cdot |dt|}{(R^2-1)^2} = \frac{R}{(R^2-1)^2}\cdot \pi \to 0 \text{ as } R \to \infty$.

In conclusion, taking the limit as $R \to \infty: \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{e^{3ix}}{(x^2+1)^2} dx + 0 = \frac{2\pi}{e^3}$

Next, we will separate real and imaginary parts: $\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\cos(3x)}{(x^2+1)^2} dx + i \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sin(3x)}{(x^2+1)^2} dx = \frac{2\pi}{e^3} + 0i$

Finally, we equal both real parts and obtain: $\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\cos(3x)}{(x^2+1)^2} dx = \frac{2\pi}{e^3}$