|

|

|

|

|

“Gosh! Nothing can travel faster than light except gossip, bias and fake narratives, and bad news. Everything has a limit except human stupidity, unbridled greed, and untamed arrogance. They obey their own laws, and that’s why there are many types of infinites,” Apocalypse, Anawim, #justtothepoint.

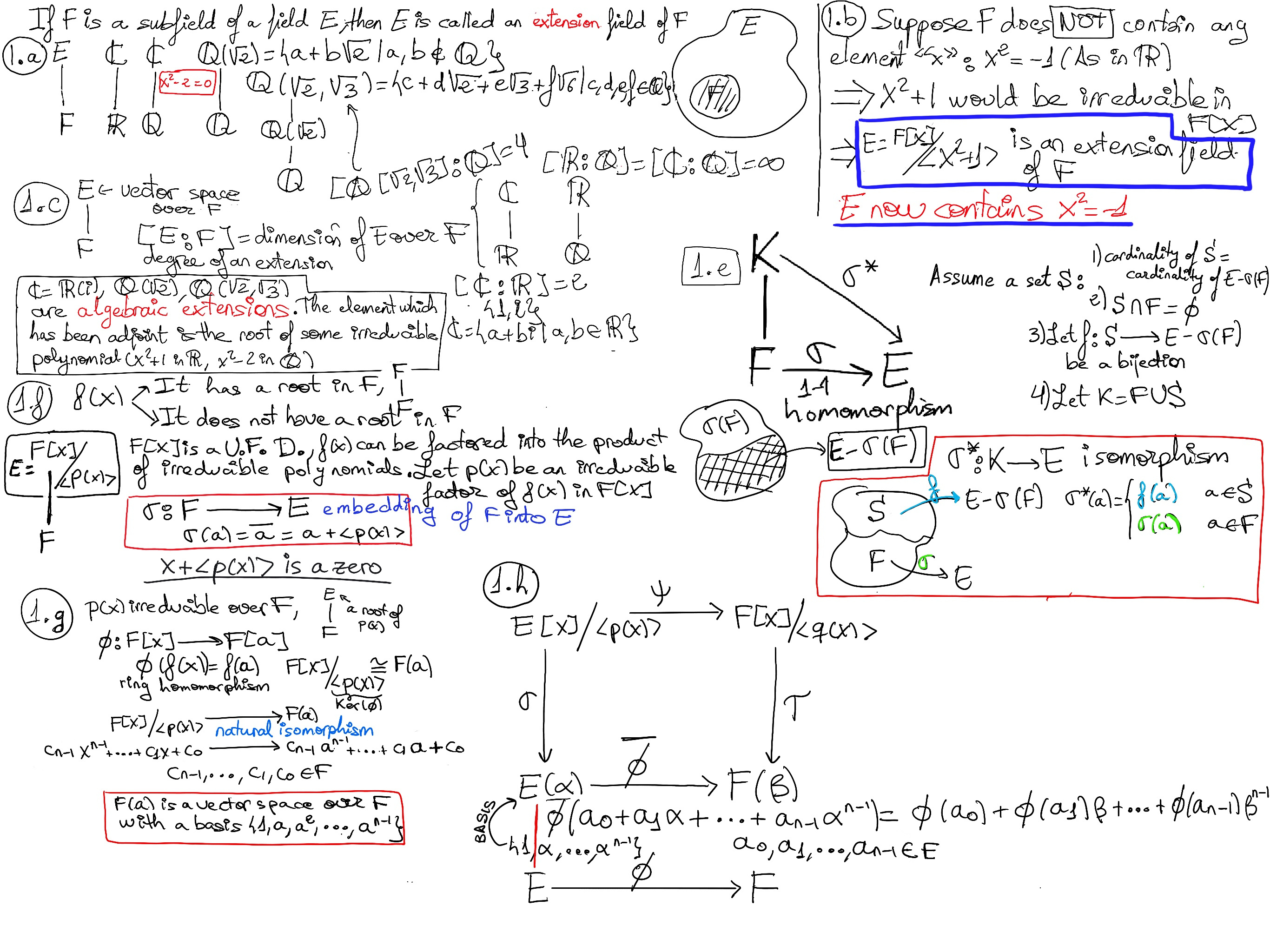

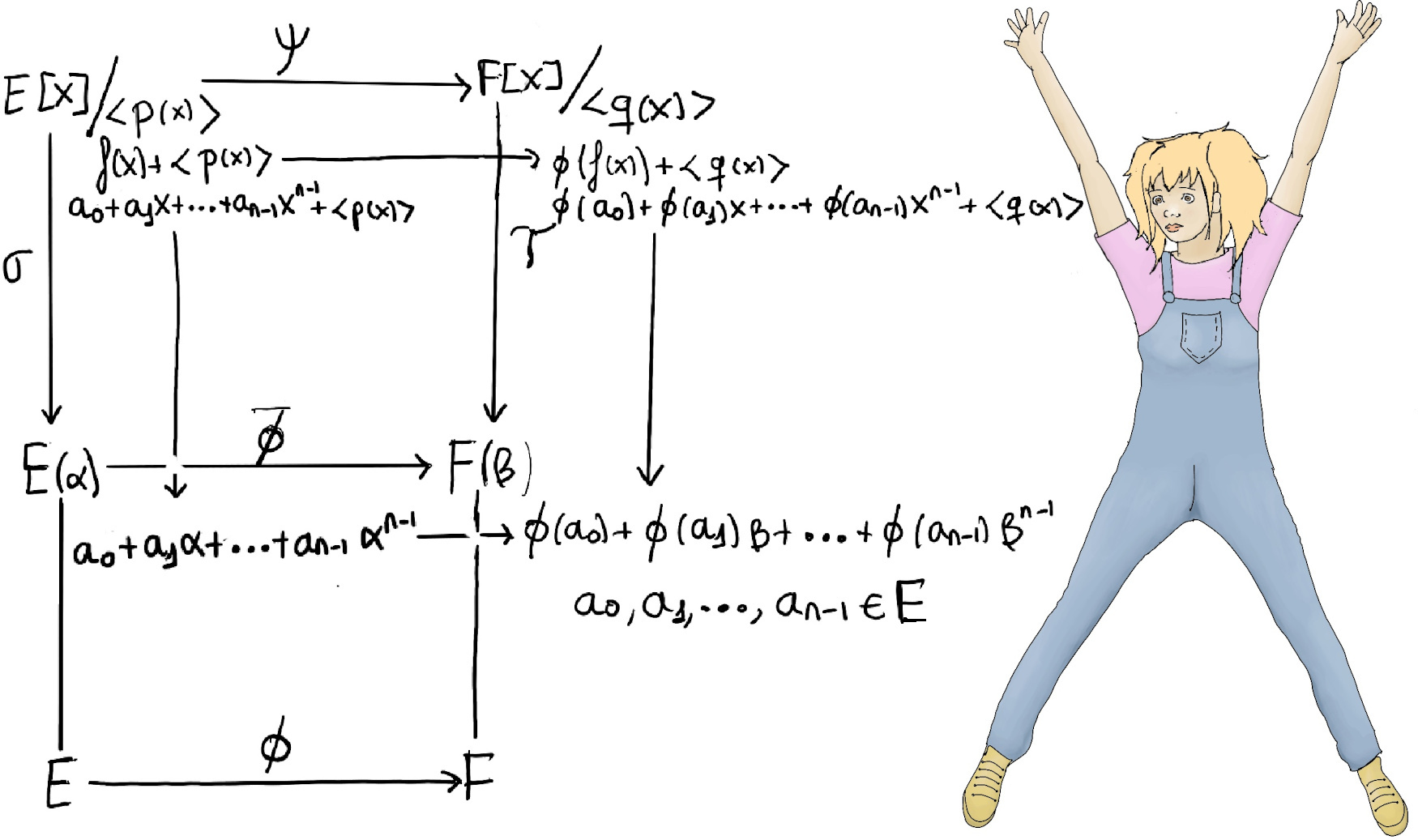

Lemma. Let ϕ: E → F be an isomorphism of fields. Let K be an extension field of E and α ∈ K be algebraic over E with minimal polynomial p(x). Suppose that L is an extension field of F such that β(∈L) is root of Φ(p(x)) in F[x]. Then, ϕ extends to a unique isomorphism $\barϕ :E(α)→F(β)$ such that $\barϕ(α)=β~ and~ \barϕ$ agrees with Φ on E (Figure 1.h.)

Proof. If p(x) has degree n, then by the previous theorem, we can write any element in E(α) as a linear combination of 1, α, ···, αn-1, i.e., a0 + a1α + ··· + an-1αn-1, therefore we can define $\barϕ :E(α)→F(β), \barϕ(a_0 + a_1α + ··· + a_{n-1}α^{n-1})=ϕ(a_0)+ϕ(a_1)β+···+ϕ(a_{n-1})β^{n-1}$

Proof. If p(x) has degree n, then by the previous theorem, we can write any element in E(α) as a linear combination of 1, α, ···, αn-1, i.e., a0 + a1α + ··· + an-1αn-1, therefore we can define $\barϕ :E(α)→F(β), \barϕ(a_0 + a_1α + ··· + a_{n-1}α^{n-1})=ϕ(a_0)+ϕ(a_1)β+···+ϕ(a_{n-1})β^{n-1}$

We can extend Φ to be an isomorphism from E[x] to F[x], which we will denote by Φ (we will abuse this notation for simplicity’s sake) defined by, $ϕ(a_0 + a_1x + ··· + a_{n-1}x^{n-1})=ϕ(a_0)+ϕ(a_1)x+···+ϕ(a_{n-1})x^{n-1}$. This extension agrees with the original isomorphism Φ: E → F because constant polynomials get mapped to constant polynomials.

Let’s call Φ(p(x)) = q(x), and Φ maps ⟨p(x)⟩ onto ⟨q(x)⟩ ⇒ ψ: E[x]/⟨p(x)⟩→F[x]/⟨q(x)⟩ is an isomorphism (it is straightforward for the reader to check it) defined by f(x) + ⟨p(x)⟩→Φ(f(x)) + ⟨Φ(p(x))⟩ = Φ(f(x)) + ⟨q(x))⟩, and we also have σ:E[x]/⟨p(x)⟩→E(α) and τ:F[x]/⟨q(x)⟩→F(β) isomorphisms defined by evaluation at α and β respectively, e.g., σ:E[x]/⟨p(x)⟩→E(α), $a_0 + a_1x + ··· + a_{n-1}x^{n-1} + ⟨p(x)⟩ → a_0 + a_1α + ··· + a_{n-1}α^{n-1}$ (where a0, a1, ···, an-1 ∈ E and the natural isomorphism from E[x]/⟨p(x)⟩ to E(α) carries akxk + ⟨p(x)⟩ to akαk). Finally, $\barϕ=τψσ^{−1}$ is the desired isomorphism.

Notice that since p(x) is a minimal (irreducible) polynomial over E, then Φ(p(x)) = q(x) is a minimal (irreducible) polynomial over F, α and β are algebraic over K and L respectively, and σ:E[x]/⟨p(x)⟩ → E(α) and τ:F[x]/⟨q(x)⟩ → F(β) are evaluation isomorphisms, e.g, σ is the identity on E and carries x + ⟨p(x)⟩ to α, τ is the identity on F and carries x + ⟨q(x)⟩ to β.

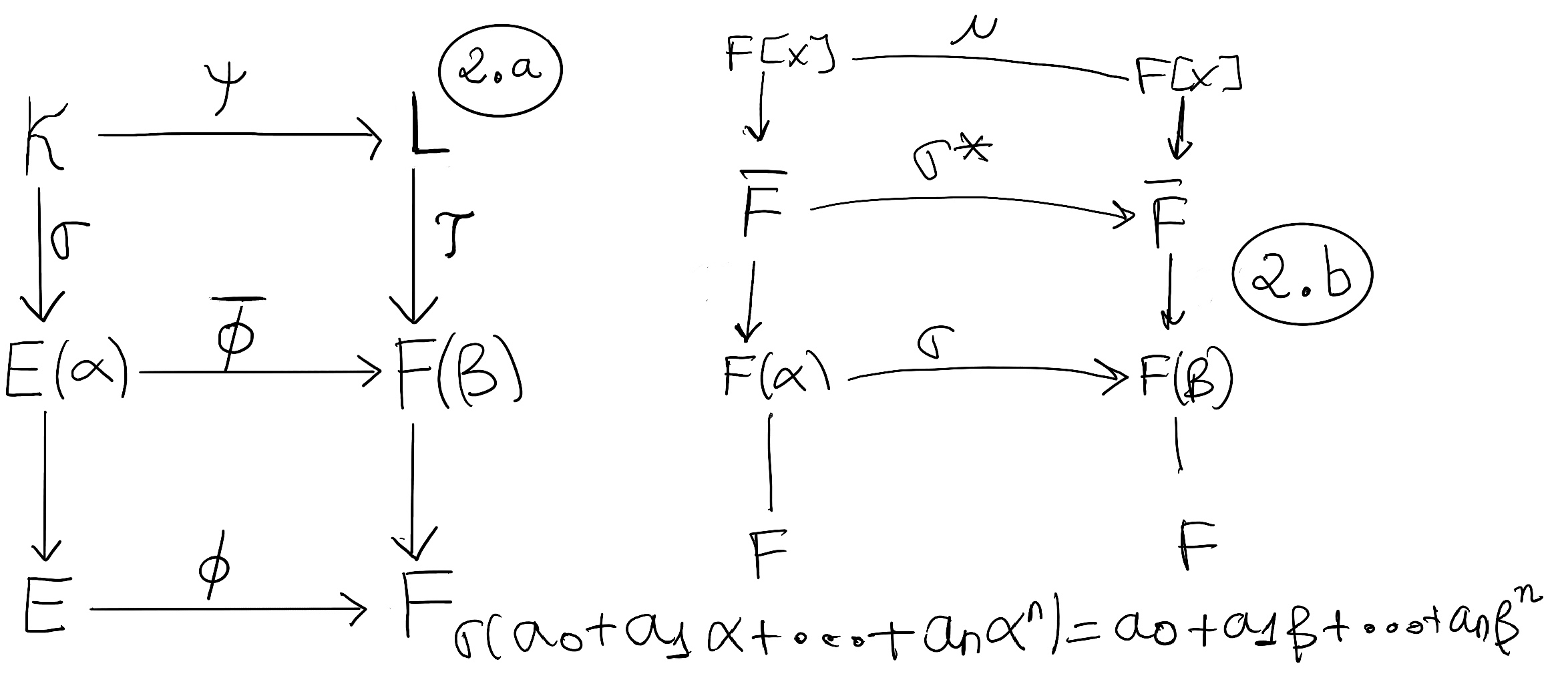

Theorem. Let ϕ: E→ F be an isomorphism of fields and let p(x) be a non-constant polynomial in E[x] and q(x) the corresponding polynomial in F[x] under ϕ. If K and L are splitting field of p(x) and q(x) respectively, then ϕ extends to an isomorphism ψ: K → L (Figure 2.a) (ψ agrees with ϕ on E)

Proof.

Let use induction on degree(p(x)) and assume that p(x) is irreducible over E (Otherwise p(x)=(x-r1)(x-r2)···(x-rm)p1(x)p2(x)···ps(x), and pi are irreducible) ⇒ q(x) is irreducible over F. If degree(p(x))=1 ⇒ K = E and L = F, Φ itself is the desired mapping and we are done.

Assume that the theorem holds for all polynomials of degree less than n. Since K is a splitting field of p(x), all of the roots of p(x) are in K. Choose one of these roots, say α, such that E ⊂ E(α) ⊂ K, and take a root β of q(x) in L: F ⊂ F(α) ⊂ L ⇒ ∃ isomorphism $\barΦ:~E(α)→F(β):~ \barΦ(α)=β,~ and~ \barΦ$ agrees with Φ on E.

α and β are roots of p(x) and q(x) respectively ⇒ p(x) = (x -α)f(x), q(x) = (x -β)g(x), degree(f(x)) < degree(p(x)) and degree(g(x)) < degree(q(x)) ⇒ [By our induction hypothesis] ∃ an isomorphism ψ: K → L such that ψ agrees with $\barΦ$ on E(α) and therefore with Φ on E.

$[\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2}, i): \mathbb{Q}] = [\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2}, i): \mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2})][\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2}): \mathbb{Q}]$ = 2·2 = 4, and that’s true because $[\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2}, i): \mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2})]$ ≤ 2 because x2 + 1 = 0 is the irreducible polynomial of i, but $\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2})⊆\mathbb{R}$ and i ∉ ℝ, in other words, $\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2}, i) ≠ \mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2})$ ⇒ $[\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2}, i): \mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{2})]$ = 2.

eix = cosx + i·sinx, where is i the imaginary unit.

$[\mathbb{K}: ℚ] = [\mathbb{K}: ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})]·[ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2}): ℚ] = 2 · 8 = 16$ because $[ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2}): ℚ]=8$ because x8 -2 is irreducible over ℚ (Eisenstein, p = 2), deg(x8 -2) = 8, and $\sqrt[8]{2}∉\mathbb{Q}$

Futhermore, $\sqrt[8]{2}∈ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})⇒\sqrt{2}∈ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})⇒$ [ξ8=$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}+\frac{i}{\sqrt{2}}$, it can be described as a polynomial of i] ξ8 ∈ $ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})(i) ⇒ K ⊆ ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})(i),$ but $ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})(i) ⊄ \mathbb{R}$ since i ∉ ℝ, hence $\mathbb{K} ⊄ \mathbb{R}⇒$It is left as an exercise, $ K=ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})(i)⇒[K:ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})]=[ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})(i):ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})] = 2, i∉ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})$, x2+1 = 0 is irreducible over $ℚ(\sqrt[8]{2})$ and deg(x2 +1) = 2.

Clearly the splitting field must contain $\sqrt[n]{a}$, but it is also true that $w^k\sqrt[n]{a}$, k=1, ···, n-1 are also roots of xn -a.

Besides, let L be a splitting field of f. If α and β are roots of f, then (β/α)n = a/a = 1 ⇒ (β/α) = ξ ⇒ β = ξα where = ξn=1, i.e., ξ ∈ L is a n-th root of unity. Fixing α, we have, in L, n distinct β, and the roots of f are given by ξα as ξ runs through these n-th roots of unity (0, 1, ··· n-1).

Solution:

💣$(\sqrt{3} + \sqrt{2})(\sqrt{3} - \sqrt{2})=1,~ so~ \sqrt{3} - \sqrt{2}$ is a multiplicative inverse of $(\sqrt{3} + \sqrt{2}) ∈ ℚ(\sqrt{2} + \sqrt{3})$ that is an extension field of ℚ, so it contains the multiplicative inverses of its non-negative elements.

$ℚ(\sqrt{2}, \sqrt{3})=ℚ(\sqrt{2})(\sqrt{3})=${a + b$\sqrt{3} | a, b ∈ ℚ(\sqrt{2})$} = {$(α+β\sqrt{2})+(γ+δ\sqrt{2})\sqrt{3}| α, β, γ, δ ∈ ℚ$} = {$α + β\sqrt{2}+γ\sqrt{3}+δ\sqrt{6}| α, β, γ, δ ∈ ℚ$}

Theorem. Let p(x) be a polynomial in F[x]. Then, there exists a splitting field K of p(x) that is unique up to isomorphism, i.e, any two splitting fields of p(x) over F are isomorphic.

Proof. Suppose that they are K, L splitting fields of p(x) over F. The result follows from the previous theorem by letting Φ be the identity from F to F.

Theorem. Let F be a field, let E = F(α) be an extension of F, where α is algebraic over F and let f ∈ F[x] be the irreducible polynomial of α over F. Let Φ: F → K be a homomorphism from F to a field K, and let L be an extension of K. If β ∈ L is a root of Φ(f), then there is a unique extension of Φ to a homomorphism Φ': E → L such that ϕ'(α) = β and fixes F.

Proof

Let β ∈ L be a root of Φ(f) ⇒ ∃σ isomorphism: F(α) ≋ F[x]/⟨f⟩, such that σ(a) = a + ⟨f⟩ ∀a ∈ F, σ(α) = x + ⟨f⟩, a0 + a1α + ··· an-1αn-1 → a0 + a1x + ··· + an-1xn-1 + ⟨f⟩.

Let evβ∘Φ be the homomorphism F[x] → L defined as follows, given a polynomial g ∈ F[x], let Φ(g) be the polynomial obtained by applying Φ to the coefficients of g (Φ(anxn + ··· + a1x + a0) = Φ(an)xn + ··· + Φ(a1)x + Φ(a0) ), then evβ∘Φ(g) be the evaluation of Φ(g) = Φ(an)xn + ··· + Φ(a1)x + Φ(a0) at β, that is, evβ∘Φ is a homomorphism from F[x] to K. evβ∘Φ(g) = Φ(an)βn + ··· + Φ(a1)β + Φ(a0)

∀a ∈ F, evβ∘Φ(a) = Φ(a), evβ∘Φ(x) = β. By assumption, β ∈ L is a root of Φ(f) ⇒ Φ(f)(β) = 0 ⇒ f ∈ Ker(evβ∘Φ) ⇒ ⟨f⟩ ⊆ Ker(evβ∘Φ) ⇒ [f is irreducible ⇒ ⟨f⟩ is a maximal ideal and evβ∘Φ is not the trivial homomorphism] ⟨f⟩ = Ker(evβ∘Φ). Then, there is an induced homomorphism e: F[x]/⟨f⟩ → L, and φ = e∘σ: F(α) → L such that φ(a) = Φ(a) ∀a ∈ F, φ(α) = β.

φ is uniquely specified by the conditions φ(a) = Φ(a) ∀a ∈ F, φ(α) = β because every element of E = F(α) can be written as $\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} a_iα^i$ ({1, α, ··· αn-1} is a basis of E), so $φ(\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} a_iα^i)=\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} Φ(a_i)φ(α)^i=\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} Φ(a_i)β^i$

To sum up, every extension φ of Φ is uniquely specified by the conditions above.