|

|

|

|

|

3r Law, There are special places in hell for those who, in times of great immorality, despicable evil, decadency, and widespread deception, maintain their indifference and neutrality, for pathological liars, child molesters, warmongers and corrupted journalists and politicians, for those who don’t flush the toilet, and, of course, for the French, Apocalypse, Anawim, #justtothepoint.

Definitions. Two subgroups H and K of a group G are termed conjugate in G if there is an element g ∈ G such that H = gKg-1. The normalizer of P, written as N(P), is {x ∈ G: xPx-1 = P}.

A p-group is a group all of whose elements have an order equal to a power of the prime number p. A finite group is a p-group if and only if its order (the number of its elements) is a power of p.

Definition. Let G be a finite group, and let p be a prime dividing the order of G. Then, a Sylow p-subgroup of G is a maximal p-subgroup of G, that is, pk divides |G| and pk+1 does not divide |G|.

Lemma. Let P be a Sylow p-subgroup of a group G. Let x ∈ G be an element whose order is a power of p. If x ∈ N(P), then x ∈ P.

Proof.

Suppose P be a Sylow p-subgroup of a group G, x ∈ G, x ∈ N(P), an element whose order is a power of p, x ∈ P?

Since P ◁ N(P) = {x ∈ G: xPx-1 = P}, i.e., P is a normal subgroup of its normalizer, we can consider the quotient group N(P)/P. Since x ∈ N(P), let K = ⟨xP⟩ a cyclic subgroup of N(P)/P.

As |x| is a power of p ⇒ |x|=pa for some a∈ ℕ ⇒ (xP)pa = xpaP = eP = P, hence |xP| must divide pa, but p is prime ⇒ |xP| is a power of p, too

[By the Correspondence Theorem, N ◁ G, every subgroup of the quotient group G/N is of the form H/N, where N ≤ H ≤ G. Conversely, if N ≤ H ≤ G, then H/N ≤ G/N] Since, P ◁ N(P), K = ⟨xP⟩ ≤ N(P)/P, there exists a unique subgroup H such that P ≤ H ≤ N(P) and H/P = K.

And then, |H| = |P|·|K| ⇒[|xP| is a power of p, K = ⟨xP⟩, the order of K is a power of p, i.e., K is a p-group (a group in which the order of every element is a power of p), and, by assumption, P is a Sylow p-subgroup] H is a p-subgroup of G, and we already know that P ≤ H. Since P is a Sylow p-subgroup and hence a maximal p-subgroup ⇒ H = P ⇒ K = H/P = P/P is the trivial subgroup ⇒[K = ⟨xP⟩ = P/P] xP = P, the identity of N(P)/P ⇒ x ∈ P ∎

Theorem. Let H and K be subgroups of a group G. The number of distinct H-conjugates of K, that is, (hKh-1) is [H: N(K)∩H].

Proof

The group G acts naturally on the set of its subgroups (Let G be a group and S denote the set of subgroups of G, including obviously K, by conjugation ·:G x S → S, g·T = gTg-1, T ≤ G, where gTg-1 is a subgroup for every g ∈ G.

We can restrict this action to its subgroup H ≤ G (·:H x S → S, h·T = hTh-1, h ∈ H).

We need to compute the size of the orbit of this H-action containing K [By the Fundamental Counting Principal, |Ox| = [G:Gx]] |OK| = [H: HK] where HK = { h ∈ H| h·K = hKh-1 = K} is the stabilizer of K via the H-conjugation action. We claim that HK = N(K) ∩ H and then, we are done.

HK ⊆ N(K) ∩ H. We know that the stabilizer is a subgroup of the group that is acting, HK ≤ H. Besides, HK ≤[We are using a restriction of a larger conjugation action by G, therefore, the stabilizer of K with respect to the H-action is a subgroup of the stabilizer of K with respect to the G-action, that is bigger, that is, HK = { h ∈ H| h·K = hKh-1 = K} ≤ GK = { g ∈ G| g·K = gKg-1 = K}] GK = N(K), thus HK ≤ N(K) ∩ H.

HK is the set of elements of H that fixes K, hKh-1 = K, GK is the set of elements that fixes K, and GK = [Because we are using the conjugation action] N(K) = {g ∈ G: gKg-1 = K}

N(K) ∩ H ⊆ HK. Conversely, if x ∈ N(K) ∩ H ⇒ x ∈ H, and x can act on K by conjugation (·:H x S → S, h·T = hTh-1, h ∈ H), x·K = xKx-1.

Futhermore, as x ∈ N(K) = GK ⇒ xKx-1 = K ⇒ x·K = xKx-1 = K ⇒[x ∈ H] x ∈ HK ∎

Sylow’s Second Theorem. Let G be a finite group and p a prime dividing |G|. Then, all Sylow p-subgroups are conjugates, that is, if P and Q are Sylow p-subgroups, then there exists some g ∈ G such that gPg-1 = Q.

Proof.

Suppose G be a finite group and p a prime dividing |G| ⇒ ∃r ∈ ℕ: |G| = prm where p ɫ m. By Sylow’s First Theorem, there exist a p-subgroup P of order pr, that is, P is a maximal p-subgroup of G, P ∈ Sylp(G).

Let $\mathbb{S}$={gPg-1: g ∈ G} be the set of all distinct G-conjugates of P, and let h * S be the conjugacy action, i.e., P x $\mathbb{S}$ → $\mathbb{S}$, ∀h ∈ P, ∀S ∈ $\mathbb{S}$, the conjugacy action h * S = h·S·h-1 is a group action.

To show it is closed, ∀ S∈$\mathbb{S}$ ⇒ S = gPg-1 ⇒ h*S = h·S·h-1 = h(gPg-1)h-1 = (hg)P(hg)-1 ∈ $\mathbb{S}$, hg ∈ G.

Let O = {P1 = P, P2, ···, Pk} be the complete orbit of all G-conjugates of P. By the previous lemma, the number of G-conjugates of P is k = [G: N(P)].

|G| = prm = [By Lagrange’s Theorem, recall that N(P) ≤ G] |N(P)|·|G:N(P)| = |N(P)|·k

Notice that as P ≤ N(P) ⇒ [By Lagrange’s Theorem] |P| = pr | |N(P)| and since prm = |N(P)|·k, there’s no p’s left that can divide k, and therefore and p ɫ |G:N(P)|=k

Let Q ∈ Sylp(G), an arbitrary Sylow’s p-subgroup. We claim that Q ∈ O = {P, P2, P3, ···, Pk} which would prove the theorem.

Since G acts on the set O = {P, P2, P3, ···, Pk} by conjugation ·:G x O → O, g·Pi = gPg-1, we could restrict it to any subgroup, in particular, Q, that is, ·:Q x O → O, q·Pi = qPq-1.

Besides, this will partition the set O into smaller sets. What is the number of distinct Q-conjugates of Pi is, by the previous theorem, [Q:N(Pi)∩Q], and by Lagrange’s Theorem |Q| = [Q:N(Pi)∩Q]|N(Pi)∩Q]| ⇒ [Q:N(Pi)∩Q]| must a divisor of |Q| = pr ⇒ all the indices [Q:N(Pi)∩Q]| are powers of p or 1. Thus, k can be written as a sum of powers of p, which shows that p | k.

Since p ɫ k, then at least one of these powers is 1, that is, there must exist some conjugate Pi∈ O: [Q:N(Pi)∩Q]| = 1 ⇒ Q = N(Pi) ∩ Q ⇒ ∀x ∈ Q (|Q| = pr), x ∈ N(Pi) ⇒ [Lemma. Let P be a Sylow p-subgroup of a group G. Let x ∈ G be an element whose order is a power of p. If x ∈ N(P), then x ∈ P.]x ∈ Pi ⇒ Q ⊆ Pi. Since Q is a maximal p-subgroup ⇒ Pi = Q ∎ Besides, k = [G:N(P)] = |Q| = [Q:N(Pi)∩Q]|N(Pi)∩Q]| = 1·|N(Pi)∩Q]| = |N(Pi)|

Notice that all Sylow p-subgroups are conjugates of each other. As conjugation is an inner automorphism on G, conjugation induces a group isomorphism between Sylow subgroups, and in particular all Sylow p-subgroups are isomorphic to each other and they all have the same order necessarily pr if |G|= prm and p ɫ m

If |G| = prm, that is, pr+1 ɫ |G| ⇒ ∃P ≤ G. By the first Sylow Theorem, |P| = pr that is maximal, so that’s why all Sylow p-subgroups have order pr.

Sylow’s Third Theorem. Let G be a finite group and p a prime dividing |G|. Then, the number of Sylow p-subgroups of G is congruent to 1 (mod p) and divides |G|, np ≡ 1 (mod p), np | |G|.

If |G| = prm and p ɫ m, the number of Sylow p-subgroups must divide m.

Proof.

As we have studied previously, G acts on SylP(G) by conjugation. By Sylow's Second Theorem, this action has a single orbit (there must exist some conjugate Pi∈ O = {P, P2, P3, ···, Pk}: [Q:N(Pi)∩Q]| = 1 ⇒ Pi = Q, one of the equivalence classes contains only a single Sylow p-subgroup), O = {P1, P2, ···, Pk}, and |O| = k = [G:N(Pi)], [G:N(Pi)] | |G|, therefore the number of Sylow p-subgroups (they are all conjugate of P) of G divides |G|.

Let P ∈ SylP(G). Then P also acts on SylP(G) by conjugation. Notice that {P} is a trivial orbit of this action (x ∈ P, xPx-1 = P, because P is a subgroup, so is close under multiplication). Claim: This action has no other fixed points, P is the only element of $\mathbb{S}$ whose orbit has length 1.

[Theorem. Let P be a Sylow p-subgroup of a group G. Let x ∈ G be an element whose order is a power of p. If x ∈ N(P), that is, xPx-1=P ⇒ x ∈P] Suppose that there is another {Q}, xQx-1 = Q ⇒ x ∈ N(Q), but as x ∈ P a Sylow p-subgroup, then [By Lagrange’s Theorem, all elements have order of power of p] ∃a ∈ ℕ such that |x|=pa ⇒ x ∈ Q ⇒ Q = P. Thus, this action has no other fixed points.

So, therefore {P}, {P2, P3···} and the class equation applies where X = SylP(G), |XP| = 1, there is only one fixed point.

|X| = |XP| + $\sum_{i=k}^n |O_{x_i}| = 1 + \sum_{i=k}^n p^{e_i} ≡ 1 (mod~ p)$ Notice that |X:C(xi)| divides |X| = |SylP(G)| = pr.

Example. Consider n = 6 = 2·3

nk = # of Sylow k-subgroup = |Sylp(G)|, then nk | |G| and nk ≡ 1 (mod p)

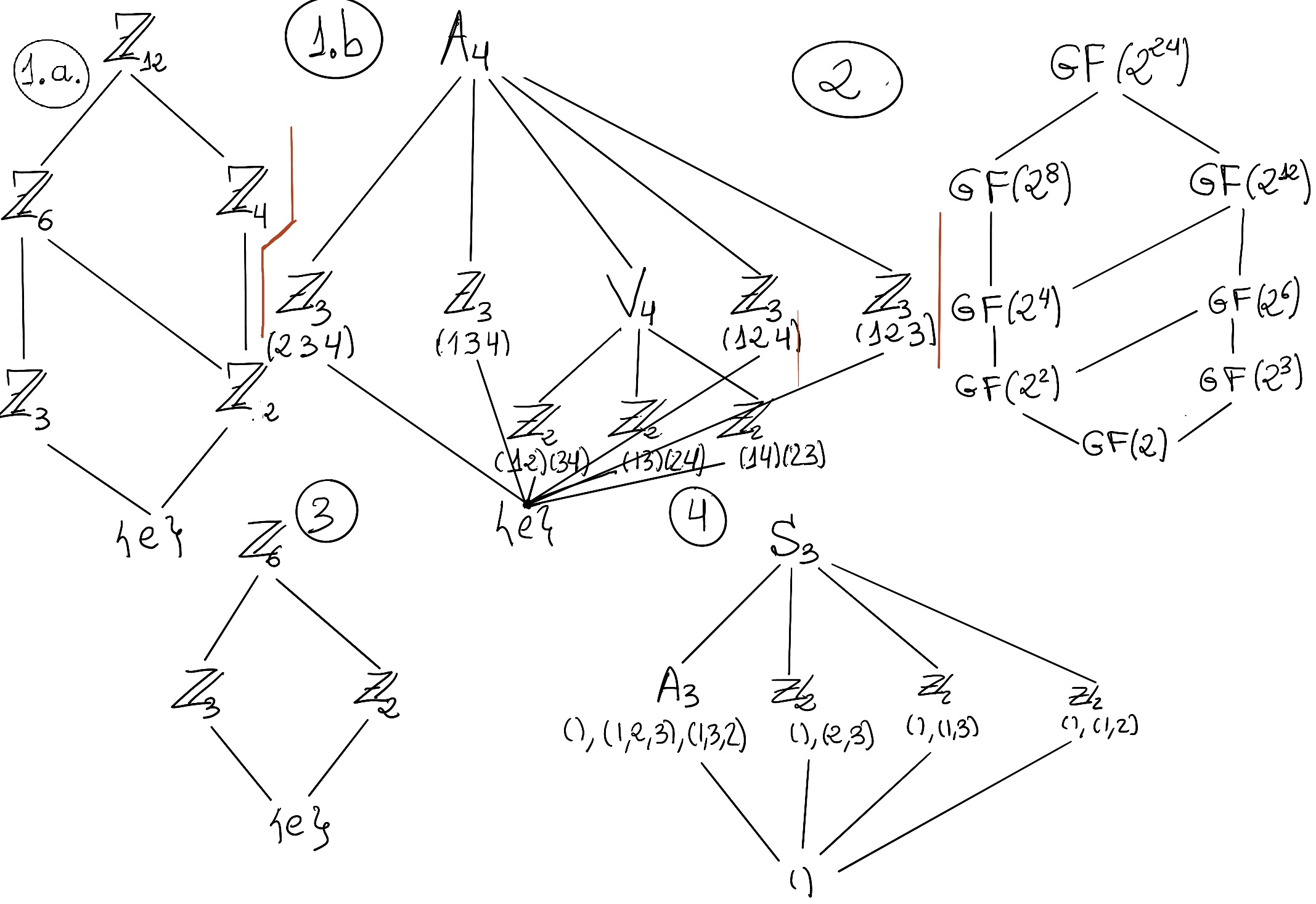

By Sylow’s Third Theorem, n3|6, n3 ≡ 1 (mod 3) ⇒ n3 = 1, and therefore any group of order 6 must have a unique (and normal) Sylow 3-subgroup but [n2|6, n2 ≡ 1 (mod 2) ⇒ n2 = 1 or 3] can have 1 or 3 Sylow 2-subgroups, e.g., ℤ6 has a unique Sylow 2-subgroup (Fig 3, ℤ3), ℤ6 has a unique Sylow 2-subgroup (Fig 3, ℤ2) and S3 has 3 Sylow 2-subgroups (Fig 4).

Consider one of the Sylow 2-subgroups of S3, say {(1), (12)}. By Sylow’s Third Theorem, we should be perfectly able to get the other two Sylow 2-subgroups from this one by conjugation: (13){(1), (12)}(13)-1 = {(13)(1)(31), (13)(12)(31)} = {(1), (23)}, and (23){(1), (12)}(23)-1 = {(23)(1)(32), (23)(12)(32)} = {(1), (13)}

Consider one of the Sylow 3-subgroups of A4, say {(), (234), (243)}. By Sylow’s Third Theorem, we should be perfectly able to get the other three Sylow 3-subgroups from this one by conjugation:

If σ = (a1a2···ak), then a1 → 2→···→ak→a1. Then, σ-1 = a1 ← 2←···←ak←a1, this is the cycle written backwards (akak-1···a1). If it is a 2-cycle: (ab)-1 = b-1a-1